Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

An aerial view of the pristine Muthurajawela wetland

Pix by Kithsiri De Mel/ Dinusha Nanayakkara

When Nirmala Priyanthi’s daughter (L. D Randima Gimhani, 13) succumbed to dengue in 2015, she said that life was hopeless afterward. A resident of Bopitiya, a coastal village about 40 minutes drive to the North of Colombo, Priyanthi links the death of her child to the many mosquito breeding sites in the neighbourhood, mainly in people’s gardens where water collects in piles of household refuse.

Sri Lanka has recorded over 27,000 cases of dengue and nine deaths for this year amidst a festering problem of solid waste management. Mosquito-borne diseases like dengue can spread rapidly in unhygienic environments where fresh water stagnates in discarded receptacles, as well as in brackish water, a problem worsened by the recent monsoon rains that have flooded lowland areas near the West coast of the country. Human incursions have eaten into the former wetlands and marshes that dotted Colombo and its suburbs, also diminishing wildlife that can keep mosquito populations down by eating mosquito larvae.

However, dengue and the complex interplay of climate change, environmental and human factors that propel it are hardly on the radar of the country which is grappling with an economic crisis of unprecedented proportions, where people are more concerned about their daily income. Health and environment lie at the bottom of the list of priority concerns. Yet, Sri Lanka’s dengue epidemics are exacting a disproportionately high health and economic toll each year. The need to apply holistic, multi-sectoral One Health approaches to eradicate the epidemic is needed now more than ever before.

Sri Lanka’s dengue crisis

Endemic to Sri Lanka, dengue is one of the most prevalent mosquito-borne diseases in the world and is in active transmission in about 90 countries. The disease is caused by the Dengue virus (DENV) which is transmitted to mainly humans as well as mammals such as cows and dogs, by the female mosquitoes of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus.

DENV has four main serotypes: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4.While infection with one serotype can confer lifelong immunity against the same serotype, infection with another serotype increases the risk of developing a severe form of the disease. Surveillance studies show that shifts from one dominant serotype in the community to another serotype can increase dengue transmission and trigger serious outbreaks. This is because people previously infected with the then dominant serotype are susceptible to the new serotype, and the community itself may have lower immunity to it. Based on limited virological studies, researchers suggest that the unexpectedly large dengue epidemic in the island in 2017, which notched up 186,101 suspected cases and 440 dengue-related deaths may have been the result of a transition from previously dominant serotypes to DENV2.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever and shock can kill vulnerable people including children and the elderly by causing internal bleeding and damaging internal organs. Globally dengue causes an estimated 20,000 deaths worldwide and about 100 to 400 million infections. Dengue epidemics also exert serious economic impacts. In just the first half of 2023, the costs of dengue control and hospitalization in the Colombo district was estimated at US$ 3.45 million. Hospitalization costs accounted for just under half of the total expenses.

People in underserved settlements find an income by segregating garbage

Spotlight on Muthurajawela

The ‘Lungs of Colombo.’ That was how the Muthurajawela wetlands were once known in Sri Lanka’s capital city, a mere 30 minute journey away by road. With mile upon mile of water plants and pristine mangrove forests that hug myriad waterways, the marsh is about 4 to 5 feet below sea level and spans a breathtaking 7500 acres. Its tributaries and river ways such as Ja-ela and Dandugam Oya ebb and flow as they mingle with the tidal waters of the Negombo lagoon, a ragged, rectangular estuary that runs Northwards before joining the Indian Ocean. But environmentalists say that the Muthurajawela wetland has fallen victim to various anthropogenic incursions over time.

That the borders of the Muthurajawela wetland sanctuary have not been demarcated, complicates the matter. A Joint Committee to conserve the Muthurajawela wetland appointed by the Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) observed that although the Muthurajawela was declared a sanctuary via a gazette notification No. 947/13 in 1996, the boundaries of the sanctuary have not yet been demarcated. The Committee also inquired into the reasons for identifying only 1285 hectares of Muthurajawela as a sanctuary even though the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) had marked 2569 hectares. Also noted was the failure of the relevant agencies to properly identify the total extent of lands in the Muthurajawela ecosystem exceeding 6000 hectares and the extent of private lands and government lands within the sanctuary.

A mangrove patch

Changing land use and climate change linked to rise in mosquito populations

In order to protect its boundaries from rapid encroachment, the residents of Muthurajawela formed several environmental groups to protect its biodiversity and ecosystems. The Muthurajawela Protection Archbishop Environment Committee (MPAEC) is one of them. “Following 2015, the Muthurajawela wetland witnessed a rapid construction boom,” said Dinusha Nanayakkara, MPAEC member who has lived near the Muthurajawela wetland since his childhood. “So far there are around 24 factories in the area that discharge a lot of waste to the nearby waterways, further increasing chances of vector-borne diseases such as dengue,” said Nanayakkara. Not far from Bopitiya in the Muthurajawela industrial zone are the oil-powered Yugadanavi Power Station and the Kerawalapitiya waste disposal plant as well as the Sobadhanavi Power plant and Pyramid Lanka (Pvt) Ltd.

|

- Dinusha Nanayakkara, MPAEC Member - |

“Dengue claimed the lives of many devotees in my parish,” said Fr. Nimal Jayantha, Parish Priest of St. Nicholas Church, Bopitiya. “Many people with political patronage started claiming certain properties coming under the purview of the Muthurajawela sanctuary as their own. In order to demarcate their boundaries, they started putting up fences and even growing commercial crops such as coconut across vast expanses of land. Some private owners started reclaiming land, paving new roadways by pumping silt from the Old Dutch Canal in the guise of clearing invasive species. There were attempts to dump garbage in environmentally sensitive areas at the heart of Muthurajawela. But with the interventions from the Muthurajawela Protection Archbishop’s Environmental Committee these efforts proved futile,” Fr. Jayantha recalled.

Such destruction of local ecosystems is warming microclimates, even while global warming is extending the habitat of mosquitoes including Aedes aegypti, the main vector of Dengue, into temperate zones, “During the rainy season, Muthurajawela soaks up the back flow from the lagoon as the sea waters rush inland,” Nanayakkara explained. “Over the weeks, excess water to drain into the lagoon via the Lellama, Negombo. The Muthurajawela wetland stores this water, like a giant sponge, preventing flooding of the surrounding lands. During the dry season the wetland systematically evaporates the water that has been stored thereby providing a cooling effect,” he added. Changing land use and the destruction of the wetlands is raising local temperatures and causing flooding, favoring mosquito habitats and breeding.

According to the 2020 freshwater fish assessment the Bandula pethiya has been found only in one location

Stories from encroached settlements

Previous studies indicate that Muthurajawela transformed itself from a mosquito-free area to an area with many dengue infections. Back in 1997, around two to five cases were reported from Muthurajawela. But by the year 2000 the number of cases surpassed 300. The birth of housing schemes in lowland areas such as Nilsirigama and Pubudugama suffer regular flooding, aggravating the crisis.

“We have been living with floods for the past 20 years or so,” mused K. Damayanthi, a resident of Nilsirigama. “The government provided us with these housing units and we weren’t informed about flooding. There’s only one access route to Nilsirigama and we face severe inconveniences during floods,” said Damayanthi. With the recent deluge, the water levels were knee-deep. “Children are unable to commute to school during heavy rains,” said another resident, Saman Perera. “It takes several days for the floods to subside given that the surrounding area is a marshland. Dengue cases are also being reported from the area and we try our best to keep our gardens clean,” he added.

|

- Sevvandi Jayakody, Conservationist and Chair Professor at the Department of Aquaculture and Fisheries – University of Wayamba |

Around 300 families have been settled in Nilsirigama, but people continue to live amidst floods, unlike in Pubudugama where some houses have been abandoned. But several people this writer spoke with opined that even though they are aware of the dengue epidemic, it is not an immediate need that they could afford to address. “These are impoverished people who find an income from contract labour. Therefore they are more focused on finding a daily income rather than discarding waste in a proper manner and making an attempt to prevent dengue,” said Upali Thilakasiri from Pubudugama.

When asked about the dengue situation in Muthurajawela this year, Public Health Inspector (PHI) for Pamunugama, H. A. K. Maheshka said around 10-15 cases have been reported so far. “Usually at least one case is being reported from these resettlement areas including Nilsirigama, Pubudugama and Sooriyamal Watte,” he added. He further said that many imported cases are also being reported. “Many people from Muthurajawela work in Colombo and there’s a tendency to contract the infection from the city as well,” Maheshka added.

Nala Handaya used in integrated vector management

Garbage menace

The Daily Mirror learned that most lowland areas have been refilled using garbage to even the terrain for housing. A senior official at the Central Environmental Authority – Gampaha who spoke on conditions of anonymity said that it has been a common practice to refill lowland areas with garbage. “They use all kinds of garbage for this purpose. With regards to Muthurajawela certain local government authorities have their private lands. Garbage is being dumped in these places and they have obtained a permit from us. But our officials visit the site frequently to ensure that they don’t disturb the Protected Area. As a result of filling land in this nature these areas are prone to floods,” she added.

The pileup of solid waste in the many waterways that dissect the marsh has clogged the passage of rainwater, forming stagnant water bodies that have become breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Likewise, land reclamation has led to the pooling of water in places where it is unable to flow to the marsh. Mosquitoes now swarm the wetlands, rainy season or dry.

Many people from Muthurajawela work in Colombo and there’s a tendency to contract the infection from the city as well,”

Many people from Muthurajawela work in Colombo and there’s a tendency to contract the infection from the city as well,”

- H. A. K Maheshka, Public Health Inspector (PHI) for Pamunugama

During our visit, this writer observed how garbage was being dumped close to a water body. The fact that this dumping site is located in the heart of an important wetland that has faced many legal obstacles remains a worrying concern. A security officer at the dumping site said that once the garbage is dumped it is separated into degradable and solid waste containers which also provides a source of income for people in underserved settlements in the surrounding areas.

The Central Environmental Authority’s Acting Deputy Director General for Solid Waste Management Chathura Malwana said that it is difficult to monitor the disposal of garbage on private lands. “Perhaps this land is acquired by the respective municipal council. But we will look into the matter and appoint a unit to look into the potential risks imposed on the sanctuary when dumping garbage at this location. Following observations if the risks are manifold we will propose an alternative location away from the sanctuary,” he added.

When the outbreak seems to have gotten out of hand we conduct fogging activities, use sprays, chemicals, larvicides,”

When the outbreak seems to have gotten out of hand we conduct fogging activities, use sprays, chemicals, larvicides,”

- Dr. Sashini Ranaweera, Medical Officer, NDCU -

Nilsirigama indundated with floods following the recent rains

Preserving wetland ecosystems

Wetlands comprise a diverse composition of biodiversity which makes it a unique ecosystem. They also include a balance of consumers and predators. “In a wetland ecosystem you can find larval stages of dragonflies, damsel flies and larvae of smaller insects such as mosquitoes as well,” said Prof. Sevvandi Jayakody, conservationist and Chair Professor at the Department of Aquaculture and Fisheries – University of Wayamba. “When mosquitoes lay eggs, they are seen on the surface. The mouths of most fish are adapted to feed on things floating on the water surface. Mosquito larvae require oxygen and therefore they are found on the water surface. Therefore most fish species feed on mosquito larvae.” She said that one indication of a healthy ecosystem is when you see different predators acting on different organisms. “Apart from fish, dragonflies and damselflies also help to keep mosquito populations at bay bringing in the checks and balances to control the spread of mosquitoes,” she explained.

Conservationists observe that with time, the species composition in most wetland ecosystems have changed with the spread of invasive species. Invasive plants such as salvinia create mats on the surface of water, blocking the supply of oxygen and air to other organisms. “As such, wetlands have been altered. On the other hand, native species are susceptible to pollution and therefore these populations are on the decline,” Prof. Jayakody added.

The IUCN Red List of species lists out a number of fish species endemic to Sri Lanka. Prof. Jayakody further said that fish named under the Genus Pethiya are of particular importance. “The Nalahandaya (Applocheilus spp) is an important species used in dengue control programmes. But it is difficult to see the nalahandaya in the wet zone. In lagoons we sometimes find a fish species named kalapu handaya. They too feed on mosquito larvae,” she added. Freshwater fish that feed on mosquito larvae including Horadandiya, Tilapia and Snakeskin Gouramies have dwindled.

Perhaps this land is acquired by the respective municipal council. But we will look into the matter and appoint a unit to look into the potential risks imposed on the sanctuary when dumping garbage at this location”

Perhaps this land is acquired by the respective municipal council. But we will look into the matter and appoint a unit to look into the potential risks imposed on the sanctuary when dumping garbage at this location”

- Chathura Malwana, Acting Deputy Director General for Solid Waste Management, Central Environmental Authority

The 2020 freshwater fish assessment indicates that 61 out of 139 freshwater fish species are endemic to Sri Lanka. The IUCN Red List already states the Bandula pethiya, Asoka pethiya and Dumbara pethiya are endangered. Of the 61 endemic species assessed, 12 point endemic species were listed as Critically Endangered (CR), 24 range-restricted species were Endangered (EN) and nine species were Vulnerable (VU). A further five species were Near Threatened (NT). For instance, even though the Kalapu handaya, was found in 22 locations and carries the Least Concern threat status as of 2020, the Bandula pethiya had been found only in one location and carries the Critically Endangered threat status as of 2020. The study states that ‘coastal wetlands such as the Muthurajawela sanctuary have drastically declined due to the introduction of invasive plants such as Annona glabra, Eichornia crassipes, and Salvinia molesta that could make most marsh habitats unsuitable for freshwater fish species.’

The study further reveals that the presence of solid waste disposal sites near the sanctuary enable the flow of leachate, containing many pollutants such as heavy metals into the waters. In an attempt to conserve these endemic species they are now legally protected under Schedule VI of the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinance.However, after 2015, Muthurajawela underwent rapid ecological destruction at the hands of people in power. Loss of biodiversity, mainly of species that feed on mosquito larvae, can cause mosquito density to rise uncontrollably and fuel the transmission of pathogens such as DENV.

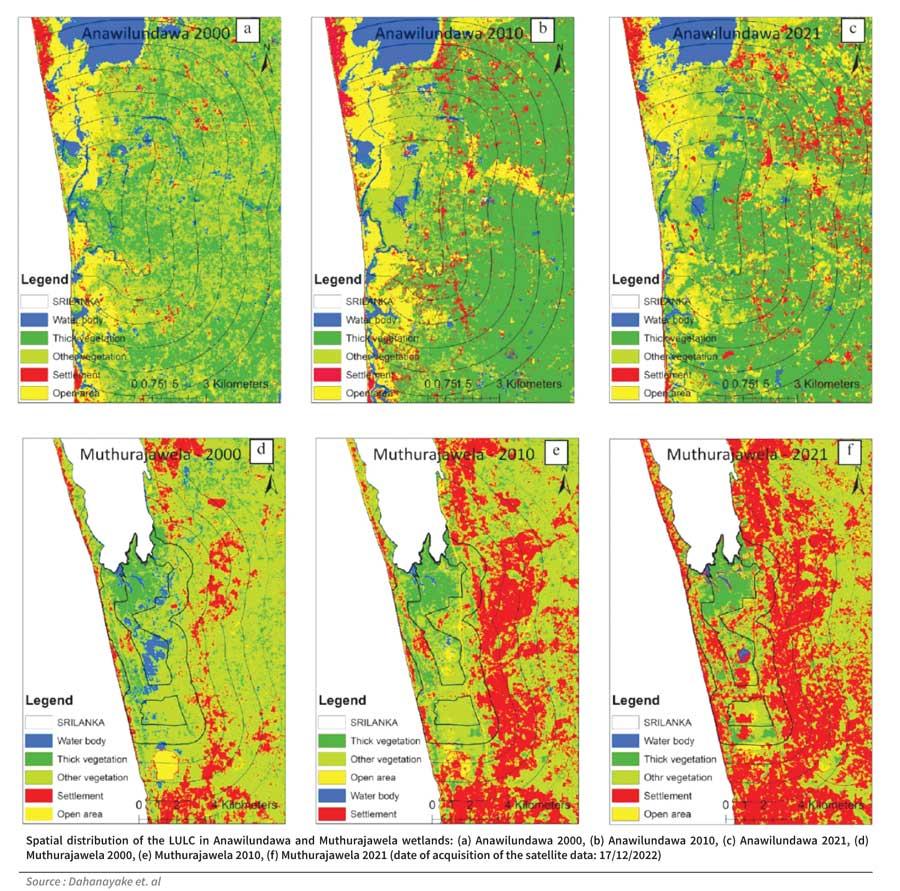

Spatial distribution of land use/ land cover in the Muthurajawela wetland from 2000-2021.

Source : Dahanayake et. al

Integrated approaches – the way forward

Back in 2020, the government raised the spot fine imposed on a person violating the Prevention on Mosquito Breeding Act of 2007 from Rs. 2000 to Rs. 5000. In early June, the Health Ministry’s Epidemiology Unit announced that legal action would be sought against 981 establishments where mosquito breeding places were detected.

However, with rapid changes in the environment the dengue menace looms, posing a threat to all citizens alike.

According to the World Health Organisation One Health is an integrated approach that has been introduced to address health threats arising from the animal-human-environmental interface. One Health recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent. In Sri Lanka, even though ad hoc attempts are being made to eradicate the dengue epidemic, local authorities now believe that a holistic approach is required to address the disease burden.

The National Dengue Control Unit (NDCU) is the apex body that carries out dengue surveillance programmes in the country. Door-to-door campaigns and cleanups are also undertaken to prevent a major dengue outbreak from taking place. “During the inter-monsoon periods we find household breeding places such as refrigerator trays, containers left under leaking sinks etc,” said Dr. Sashini Ranaweera, Medical Officer at the NDCU. “Such breeding sites are more common in apartments and indoor places. When the outbreak seems to have gotten out of hand we conduct fogging activities, use sprays, chemicals, larvicides,” said Dr. Ranaweera.

For integrated vector management, biological methods such as larvivorous fish are being used to feed on mosquito larvae. Species including guppy (Poecilia reticulata), dandi (Rasbora daniconius) and juvenile stages of Tilapia spp (Orechromis mossambicus and O. niloticus) are used for the purpose. “We also do health promotion and risk communication to raise awareness on the burden of dengue,” Dr. Ranaweera added. Container collection programmes are also being conducted in the Muthurajawela area apart from community-based programmes to educate the public on the dangers of dengue. “We also conduct a school-based recycling programme to empower children to discard waste in a responsible manner. All these approaches are being done in our capacity to keep dengue at bay,” said Pamunugama PHI Maheshka.

Even though the One Health concept is new to Sri Lanka, Dr. Ranaweera affirmed that it would be integrated into the National Dengue Control Action Plan for 2024-2028. “For this, all stakeholders including the Health, agriculture and wildlife ministries and respective departments need to collaborate to bring about a holistic approach to eradicate the dengue outbreak,” she underscored. Article 27 of the Sri Lankan Constitution provides that the state shall protect, preserve and improve the environment for the benefit of the community. The more it is ignored and the unhealthier the environment becomes, the more vulnerable it would become for diseases such as dengue to thrive.

Muthurajawela - A pristine ecosystem disturbed by human influences

(This story was supported by the InterNews Earth Journalism Network)