Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

When Dr. Priyanga Pupulewatta bought his new Toyota Prius for 7.4 million rupees in 2017, he knew that he was getting a good deal: “the car had just arrived in Sri Lanka and that was the dealer’s price at the time.”He was correct: today, that car regularly sells for 12 million rupees or higher. However, in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, that car usually sells for a third of the price in Sri Lanka. The reason? Aggressive government taxation. While Dr. Pupulewatta would have been able to afford his car at the standard Sri Lankan price, that price difference makes car ownership unaffordable for many.

When Dr. Priyanga Pupulewatta bought his new Toyota Prius for 7.4 million rupees in 2017, he knew that he was getting a good deal: “the car had just arrived in Sri Lanka and that was the dealer’s price at the time.”He was correct: today, that car regularly sells for 12 million rupees or higher. However, in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, that car usually sells for a third of the price in Sri Lanka. The reason? Aggressive government taxation. While Dr. Pupulewatta would have been able to afford his car at the standard Sri Lankan price, that price difference makes car ownership unaffordable for many.

A key criticism of Sri Lankan vehicle taxation is that while most governments implement one standard tax, Sri Lanka implements about six. This leads to exorbitant levels of direct and indirect taxation, ultimately hurting the vehicle buyer. The end result is that car ownership is viewed as a luxury in Sri Lanka, and millions of lower middle class and lower class citizens cannot afford a vehicle.

High vehicle taxation would be somewhat justified if Sri Lanka had an efficient and punctual public transit network; as is the case in countries like Singapore or the UK where citizens can live comfortable lives without a personal vehicle. However, this is not the reality of the current situation and so it is clear that Sri Lanka’s taxation strategies need to be rethought.

The issue of car taxation becomes especially controversial as politicians and government employees receive permits that reduce much of the tax burden. This cost is ultimately shouldered by the taxpayer. For example, the loss of tax revenue due to permits being distributed prior to the 2015 Parliamentary Elections has been estimated to be seven billion rupees. During the 2016 Budget Reading, then Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake proposed ending the distribution of permits as it had led to approximately 147 billion rupees of lost revenue between 2012 and 2015. The proposal was not put into action. The permit system also enables widespread corruption as many tend to be distributed immediately prior to elections and as many MPs and officials resell their permits to private citizens. This is undoubtedly unfair to the average citizen, who often has to pay three or more times the cost per vehicle as a permit holder.

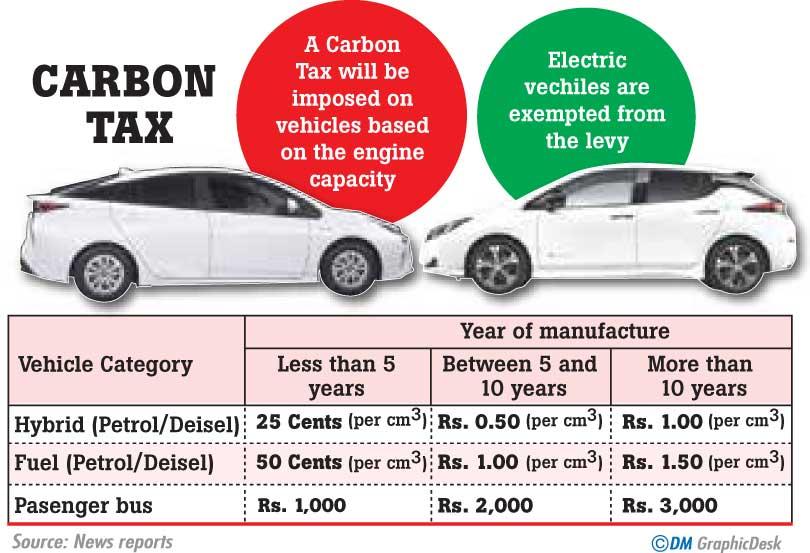

The 2019 Carbon Tax is the latest in a long line of car taxes imposed by the Government of Sri Lanka (GoVT) in a desperate attempt to balance the national deficit. The carbon tax was implemented despite the existence of an emissions tax, and only takes into account a vehicle’s age and engine capacity instead of its emission figures. The new tax especially targets less well-off citizens, who tend to have older vehicles and who feel that the government should not assume that older vehicles produce higher levels of emissions. Many have criticised the government for increasing taxes that price nearly all vehicles out of the reach of the middle class as popular hybrid models have also seen price hikes of over 500,000 rupees.

The new carbon tax has many flaws, including the price hikes on already overpriced vehicles and the targeting of the poor and elderly, but its two major flaws are that it does not apply to government officials and the way that the funds collected are spent. The arbitrary nature of the new tax has been heavily criticised as only vehicles owned by private citizens are being taxed and not vehicles owned by the government nor its institutions, despite the fact that many government vehicles are old, large, poorly maintained gas guzzlers. 60-70% of government vehicles are older than 10 years and have mileage over 300,000 km according to a study conducted by the University of Moratuwa; the study also mentioned that there is a “lack of proper preventive maintenance policies”. Another point of contention is that the income that the government receives from the tax-expected to amount to 2.5 billion rupees annually-is not being spent on environmental protection mechanisms, which should be the purpose of any ‘green tax’. Executive Director of the Center for Environmental Justice Hemantha Withanage agreed with this view, saying, “Where is this carbon emission tax going? Sri Lanka has no special trust fund to reduce carbon emissions so the tax will not help reduce emissions. Even if we wanted to walk and avoid using cars and trishaws, we cannot walk or cross main roads. The government should spend the money to address this and to improve the quality of public transportation.”

Withanage further explained that the carbon tax targets the wrong citizens, “The carbon tax should be charging heavy vehicles. There are no special high charges for heavy vehicles that pollute more. Instead, Sri Lanka is charging from poor people: motorcycles are not contributing heavily but they are highly taxed.” He also pointed out that even developed countries that pollute heavily have not imposed a carbon tax.

modern EVs with a range of 300 km will receive a cost increase of 2 million rupees

When France attempted to implement a carbon tax in 2018 that led to an increase in fuel prices, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in the violent ‘Yellow Vest’ protests that forced the government to offer rebates and subsidies on fuel for low income families. However, as the government has not removed the carbon tax, the protests continue and have expanded. Furthermore, France’s carbon-dioxide emissions per capita is approximately 4.6 metric tons whereas Sri Lanka’s is less than 0.9 metric tons.

It is also of note that the main assumption behind the carbon tax is that an individual with an older and/or large engine vehicle causes more harm to the environment than an individual using a new vehicle with a small engine. However, this is not always the case as it depends on the driver’s usage of the vehicle. For example, an elderly retiree using his large sedan for a weekly shopping trip would be causing less harm to the environment than an office worker who drives her subcompact on a daily basis. Ergo, the logical implementation of the carbon tax would be to tax an individual based on the number of miles he or she covers per annum. The technology to record this already exists and has been utilized by Singapore, where Electronic Road Pricing gantries mounted along most major roads communicate with an In-Vehicle Unit (IU) and deduct money from a stored-value card inserted in the IU. The system would also allow for open road tolling to be implemented in Sri Lanka which would enable vehicles to not stop or slow down to pay tolls on the highway, thus saving time for drivers.

In an effort to appear environmentally conscious, the government has reduced import taxes on electric vehicles (EV) with a motor capacity of below 70 Kw, despite the fact that the most popular EV in Sri Lanka, the Nissan Leaf, has an 80 Kw motor and most modern EVs have larger motors of 150 Kw or more. In addition to this, many EVs do have a carbon footprint as their emissions are offset to a coal, oil or diesel power station (52% of Sri Lanka’s energy is produced from fossil fuels, according to a United countries Development Programme report) and because they generate a larger carbon footprint during their manufacture than fossil fuel vehicles. This has led many to question why they have been granted exemption from the carbon tax.

Withanage explained the mentality of the Sri Lankan EV buyer, “People here think that if they buy an EV, they are living a green, zero-emissions lifestyle. They don’t understand that electricity comes from coal power. Many countries such as Korea get power from solar on top of roofs, bus stops etc. If Sri Lankans charge their EVs from solar power, then they can say that they have zero-emissions.” The slow pace of Sri Lankan government adoption of renewable energy production means that the transition to 100% renewables for the National Grid will not occur until 2050 at the earliest.

However, if the purpose of high vehicle taxation is to reduce petrol and diesel consumption and therefore reduce the drain on the national balance of payments, the government should embrace EVs considerably more whole heartedly- for example, offering tax breaks to all EV buyers instead of only those purchasing electric tuk tuks and bicycles/motorcycles (the vehicles with motors smaller than 70 Kw). Withanage stressed that internal politics are interfering with the implementation of EVs leading to problems like dramatic tax variations over the years. Kia Lanka Limited Chairman Mahen Thambiah felt that the government should mirror the actions of Western governments regarding EVs, saying, “EVs are still more expensive than petrol vehicles, so most governments have given concessions. Here the government only gives concessions for small motors. The tax components need to be reduced.” Kia, a global leader in the manufacture of affordable EVs, does not import any of its EV models to Sri Lanka as the taxation makes them “not competitive.”

For EVs, the CIF value will be 6 million rupees

The government’s habit of finding unconventional and often ludicrous methods of defining a ‘luxury’ car has often been beset with criticism, especially in regards to the 2019 luxury tax. A new luxury tax has been recently implemented in addition to already significant import duty and other taxes (‘green’ and otherwise) on all new vehicles that have been progressively increasing over the years.

Speaking to the Daily Mirror Vehicle Importers Association of Sri Lanka Chairman Ranjan Peiris explained how luxury vehicle taxation in Sri Lanka in 2019 operates, “Earlier, any petrol vehicle over 1800cc or diesel vehicle over 2300cc was liable for the luxury tax. When this amendment is passed, any vehicle which has a CIF value of over 3.5 million is taxed as a luxury vehicle.” For EVs, the CIF value will be 6 million rupees. A vehicle’s CIF value is the total cost of the vehicle, its insurance and its freight to Sri Lanka. In the Western market, any new vehicle costing 3.5 million rupees (not including insurance or delivery) would be considered extremely low-end. While the move away from defining a car’s classification based on engine displacement is welcome, many feel that the government’s CIF value for a luxury car is absurdly low. Peiris stressed, “I don’t think this system is correct. Even a Honda Civic would be classed as a luxury car. I don’t see a 1000cc Honda Civic as a luxury car.”

Speaking at a press conference, Mr. Peiris said, “Most of the vehicles used by the ordinary people such as Toyota Premio, Toyota Axio, Honda Vezel, Toyota CH-R and Honda Grace fall under the luxury tax category.” This particular tax significantly affects buyers of EVs or hybrids, as the battery manufacturing process causes the total manufacturing cost to be relatively high- for example, modern EVs with a range of 300 km will receive a cost increase of 2 million rupees from the new luxury tax. The new luxury tax also affects imported vehicles that are locally manufactured, which removes the argument that it was implemented to protect local industry (similar to the Australian government’s strategy). For reference, the Australian government imposes a luxury tax on vehicles costing over 8 million rupees- which is approximately equivalent to the base price of a 2019 Audi A5 coupé. If such a scheme were implemented in Sri Lanka, it would be possible for automobiles to be purchased by many lower and lower-middle class citizens, thus considerably improving their quality of life.

The government had made the VET compulsory for the renewals of annual revenue licences only to increase government revenue

Despite the government announcing lofty goals to ensure that all vehicles comply with Euro 4 emissions standards in 2018, it is not uncommon to see poorly maintained vehicles emitting thick black smoke in clear violation of these standards. The lack of police spot checks to apprehend blatant offenders compounds the problem. In 2012, then Director (Traffic) SSP K. Arsaratnam said that the police assist RMV inspection officials to carry out spot checks, and advise them to get the vehicles repaired. However, penalties are rarely imposed, even today.

The government makes between 415 and 1660 rupees per vehicle from emissions testing. As the tests need to be carried out annually for many of the nation’s over 7 million registered motor vehicles, it is a significant source of revenue for the government. However, as a faulty or aging vehicle failing the test may cost a large amount to repair, many vehicle owners simply bribe the staff at a Vehicle Emission Testing (VET) facility for the certificate.

Allegations of corruption at VET facilities are widespread. Between 2008 and 2013, over 300 centres had been dismissed by the Department of Motor Traffic (DMT) for not maintaining standards and for issuing false certificates and test reports for motorists who bribed their staff. Many were allowed to reopen later. Speaking with the Daily Mirror previously, prominent Sri Lankan racing driver Dilantha Malagamuwa explained why he disliked VET, “It should be withdrawn because nothing towards the betterment of the environment takes place. The progress of the VET can be seen when we look at the roads,” he said. “The government had made the VET compulsory for the renewals of annual revenue licences only to increase government revenue, but it had not helped reduce environmental pollution,” He elaborated on the VET’s ineffectuality, saying, “80 percent of the vehicles fail the VET. More vehicles should be taken out from the road as they are unfit and polluting. But so far no vehicles had been removed from the road for failing VET.” The fact that only two major companies run VET facilities has also been a cause for concern, as some point out that it monopolizes the industry and stifles competition.

However, some people believe that despite their flawed execution, VET is a vital first step to reducing pollution in Sri Lanka. Withanage explained that, “The VET is a good plan which brought the concept of pollution to the forefront. If there was no VET, I cannot imagine how polluted cities like Kandy would be right now. 15 years ago, every other vehicle was emitting thick black smoke; now, it is greatly reduced. The VET has procedural issues and a lot of corruption, but it is still important.”