- Activists and families of victims submit recommendations for addressing Sri Lanka’s enforced disappearances to Presidential Election candidates

- The mothers in the North have no faith in the Office on Missing Persons. That’s because seeking the truth and issuing justice has not been fulfilled. That’s why they are asking for international investigations

- On International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances activists and families of the victims of enforced disappearances came together to remember loved ones and demand justice

- For decades, in Sri Lanka, enforced disappearances have been a tool used to suppress political dissent and combat ‘terrorism.’

- There is substantial evidence to suggest there are thousands more cases of enforced disappearances that haven’t been accepted by any police station or reported to various commissions

- During the final stages of the civil war, many people disappeared—some at the hands of the LTTE and others by security forces and paramilitary groups

- Parents of victims of enforced disappearances are now elderly and lack proper housing, employment to support themselves

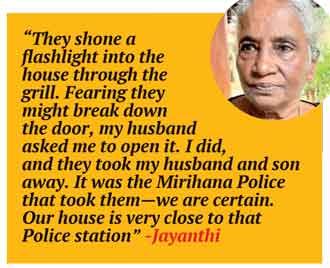

“This is the plate my husband used to have rice in, and this is the mug my son used to drink tea from,” Jayanthi shared with the Daily Mirror, gently stroking a plate and mug displayed at the entrance of the Mihilaka Hall at the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall (BMICH) on August 30.

Late one night in December 1989, Jayanthi’s husband, Newton Amarasinghe, and their only son, Janaka Chandana Amarasinghe, were allegedly taken by officers from the Mirihana Police Station, which was in the vicinity of their home. Thirty-five years later, the duo have still not

|

The plate and mug belonging to Jayanthi’s husband and son displayed at the entrance of the Mihilaka Hall at BMICH on August 30 (Photo by Safrah Fazal)

|

returned and no information has been revealed by officials on their whereabouts.

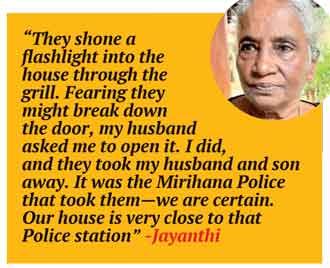

“They came around 11 p.m. My husband and son were fast asleep. They banged on the door, asking for my husband. They shone a flashlight into the house through the grill. Fearing they might break down the door, my husband asked me to open it. I did, and they took my husband and son away. It was the Mirihana Police that took them—we are certain. Our house is very close to that Police station. At night, we often saw men in black suits leaving on racing bikes. The group that came to our house was dressed in similar attire. We weren’t allowed to file a report at the Police station either,” Jayanthi claimed.

Janaka’s clothes and other possessions still remain safely at home in the event that he returns. “Even if my husband is no more, I don’t know if my son will appear from somewhere he is hidden. I’m waiting for him. I’m hoping he would return. I don’t even see them in my dream, so I think perhaps they are hidden somewhere,” Jayanthi solemnly told Daily Mirror.

This journalist met Jayanthi at an event organised at BMICH in observance of the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, which falls on August 30. Activists and families of the victims of Sri Lanka’s enforced disappearances since the early 1970s came together on this day to remember their loved ones and demand justice that has not been served to them thus far. Carrying banners and photographs of their loved, ones who were forcibly disappeared, they carried their grievances to the United Nations Compound in Colombo 07, as well as prominent Embassies and High Commissions in Colombo seeking intervention in receiving answers and justice.

Sri Lanka ranks 2nd in enforced disappearances

Sri Lanka ranks 2nd in enforced disappearances

Sri Lanka ranks second globally in enforced disappearances, based on complaints reported to the United Nations (UN) Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances. However, there is reportedly substantial evidence to suggest that there are thousands more cases of enforced disappearances that have not been accepted by any police station or reported to the various commissions appointed in the country from time to time.

The disappearances of thousands of people, allegedly by the Government and associated military groups, occurred predominantly during the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) uprising of 1971 and its insurgency in the late 1980s, the riots of 1983, and during and after the civil war. During the final stages of the civil war, many people disappeared—some at the hands of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), others by security forces and paramilitary groups. However, these disappearances didn’t end with the conclusion of the war. A significant number of disappearances have been reported since 2009.

For decades, in Sri Lanka, enforced disappearances have been a tool used to suppress political dissent and combat ‘terrorism.’

Progressive steps during Yahapalana regime

The Yahapalana Government of 2015, in line with UN Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1, took some positive steps to address enforced disappearances by establishing the Office on Missing Persons (OMP) and the Office for Reparations. However, tangible progress on the ground towards comprehensively resolving individual cases has remained stagnant or limited. While these initiatives have been welcomed, activists and families of the forcibly disappeared argue that, apart from issuing Certificates of Absence and providing Interim Relief, the OMP hasn’t succeeded in uncovering the truth about enforced disappearances, which is its primary responsibility.

A ‘Certificate of Absence’ is a legally valid document used as a proof of absence, or to establish the status of a missing or disappeared person, enabling a relative of the missing or disappeared person to exercise certain legal rights on behalf of him/her, including access to welfare services and other administrative functions. Interim Relief is a temporary measure of providing assistance amounting to Rs. 6,000 monthly (for two years) to families of missing and disappeared persons until reparations are provided.

Furthermore, in 2018, the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Act, No. 5 of 2018,

was passed, criminalising enforced disappearances. However, activists and families emphasise that enforced disappearances that occurred before 2018 cannot be prosecuted under this law.

The Story of Padmawathi’s brother and husband

In 1988, Padmawathi was just 18 years old. Her brother, who was preparing for his Advanced Level Examination, received a letter warning him of a possible threat to his life and urging him to leave the village.

A week later, a group—whom Padmawathi claims were members of the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya—arrived at their home, dragged her brother onto the street, stabbed him, and shot him, leaving him to die.

Padmawathi’s husband, who was a driver by profession, was allegedly abducted by the Army on the night of December 2, 1988.

“To this day, my husband hasn’t returned home, nor have I heard anything about him. My husband was taken by the Government, while my brother was killed by those who oposed the government. I am still seeking justice,” Padmawathi shared.

Echoes from the north

Echoes from the north

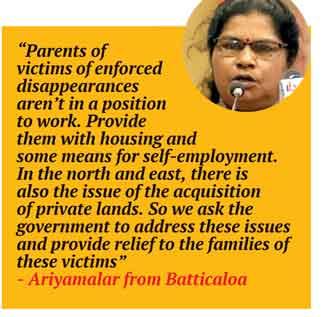

The plight of families in the north, especially during the civil war, is well known. Representing these families, Ariyamalar from Batticaloa addressed the gathering: “In my family, three people were made to disappear at the same time. In my area, most families have members who disappeared just like mine. We are yet to receive justice for this, and even today, we are still struggling for justice. It has been seven years since I joined the Families of the Disappeared organisation and have been actively involved in their work.”

She added that the parents of victims of enforced disappearances are now elderly and lack proper housing and employment to support themselves. “Parents of victims of enforced disappearances aren’t in a position to work. Provide them with housing and some means for self-employment.

In the north and east, there is also the issue of the acquisition of private lands. So we ask the government to address these issues and provide relief to the families of these victims,” Ariyamalar asserted.

Disappearance of Jennifer’s son and 10 others in 2008

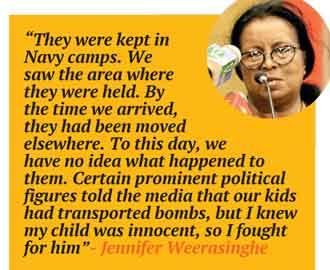

On September 17, 2008, Jamaldeen Dilan, who was travelling with four friends, was allegedly abducted by the Navy seeking ransom. Along with them, six others were also taken. Jennifer Weerasinghe, Dilan’s mother, has been frequenting courts for 15 years, seeking justice and some indication of what happened to her son and his friends, who were proven to have no involvement in any terrorist or anti-

government activities.

“They were kept in Navy camps. We saw the area where they were held. By the time we arrived, they had been moved elsewhere. To this day, we have no idea what happened to them. Certain prominent political figures told the media that our kids had transported bombs, but I knew my child was innocent, so I fought for him. The courts confirmed that my child was not involved in any illegal activities,” she said.

Weerasinghe added that after 10 long years, her case was brought to a trial-at-bar by the Attorney General’s (AG’s) Department. However, four years have passed since then, and justice has still not been served. “The vehicle that my child and his friends travelled in is still with the Navy, but there is no information about their whereabouts.

“Fourteen Naval officers, including former Navy Commander Admiral Wasantha Karannagoda, were indicted. To date, Karannagoda hasn’t appeared in court. There are 667 charges against him, with 200 witnesses and 14 suspects involved. I didn’t go investigating who took these children—the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) did. Karannagoda has political connections, and the AG’s Department is protecting him. The CID officer, Nishantha Silva, who was fully involved in my case, had to seek asylum because he feared for his life. Will I ever receive justice from the Government and the AG? Will I ever get my child back?” Weerasinghe questioned.

Five members of Mallika’s family disappear

In Galle District, on the night of January 11, 1989, a group claiming to be the police forcibly took away Wijerathna, the father of a toddler.

To date, there has been no information about him. Mallika, Wijerathna’s wife, is still seeking answers as to why and where her husband was taken, and whether he is alive. Wijerathna is not the only person in Mallika’s family who was forcibly disappeared—four other loved ones were also abducted, with no trace to date.

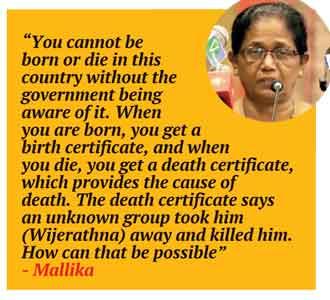

“You cannot be born or die in this country without the government being aware of it. When you are born, you get a birth certificate, and when you die, you get a death certificate, which provides the cause of death. The death certificate says an unknown group took him (Wijerathna) away and killed him. How can that be possible? We have a right to live in this country. Where are our human rights? Is it fair to take innocent lives in the name of preventing terrorism,” Mallika questioned.

She claimed that her husband, who was not part of any anti-government groups, was taken away by the police in vain. To this day, despite the establishment of new laws and complaints to the OMP, justice hasn’t been served for her family. “The mothers in the north have no faith in the OMP. That’s because seeking the truth and issuing justice haven’t been fulfilled. That’s why they are asking for international investigations. They have no faith in the country’s law. We will not give up this fight until our last breath,” she said.

“The hands of every person in power are covered with blood,” Mallika charged, adding, “None of the governments that were in power were interested in finding the truth and issuing justice to the victims of enforced disappearances and their families. We don’t want any more election promises; we are sick and tired of hearing them. Since 1994, although people made election promises, they haven’t presented an appropriate programme of policies. That’s what we have brought forward through our programme.”

Shirked promises of past governments

According to Mallika, activists and families of the forcibly disappeared are disheartened and frustrated by the false promises made by those seeking power, only to abandon them as soon as they assume office.

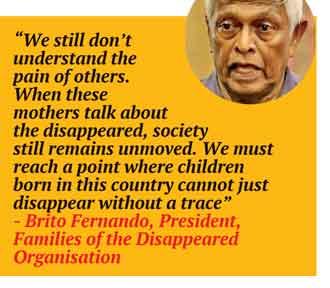

Brito Fernando, President of the Families of the Disappeared organisation, emphasised the need for society to be sensitised to the pain of the mothers and loved ones of the disappeared. “When parents cried in 1971, people were unmoved because the victims were JVP members—they said, ‘Our children were not JVP.’ In 1989, when people were dragged away, neighbours justified it by saying they were from the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya, so it was okay if they were killed; hence, they remained silent. When people were killed in the North, they justified it by saying they were Tigers who were going to split the country in two. They said, ‘Even if we don’t have food to eat, we need this country to live in; so it’s good if they are killed.’ That’s the type of country we live in. We still don’t understand the pain of others. When these mothers talk about the disappeared, society still remains unmoved. We must reach a point where children born in this country cannot just disappear without a trace.”

Fernando also spoke about the hypocrisy of some political leaders, saying, “Some politicians have marched with us and held protests with us, but once they assume power, they carried out disappearances even more effectively than others. We aren’t asking that you harm the soldiers; but there is a small group within the military who acted outside the law. Punish those criminals, not the entire tri-forces and police. In 1971 and 1989, there were morally upright persons within the tri-forces and police who saved innocents.”

He further urged the candidates of the Presidential Election to accept the recommendations put forward by the rganization. Fernando also challenged the candidates to make a public statement about their stance on the issue concerning the victims of enforced disappearances.

Recommendations for successive government

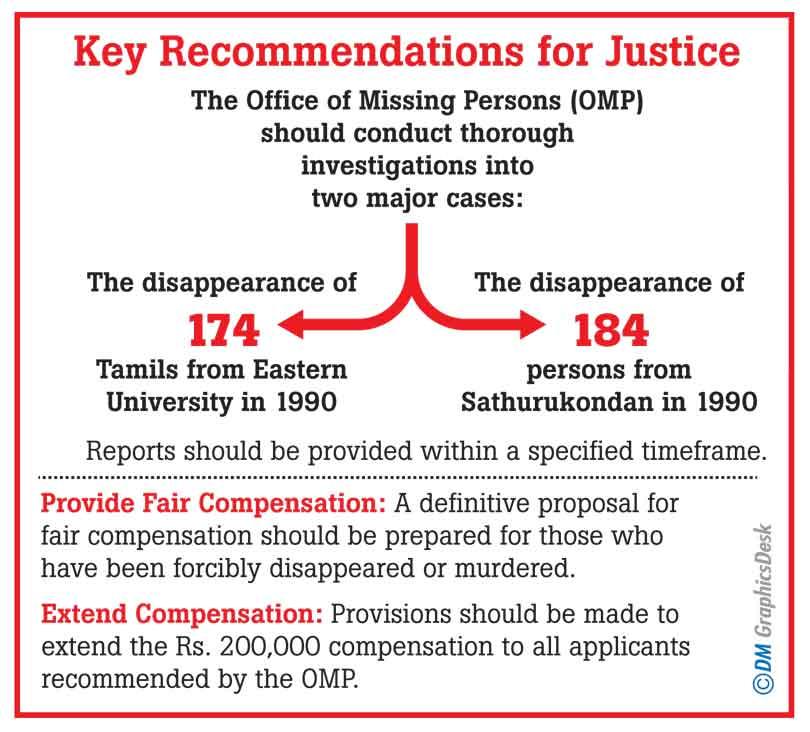

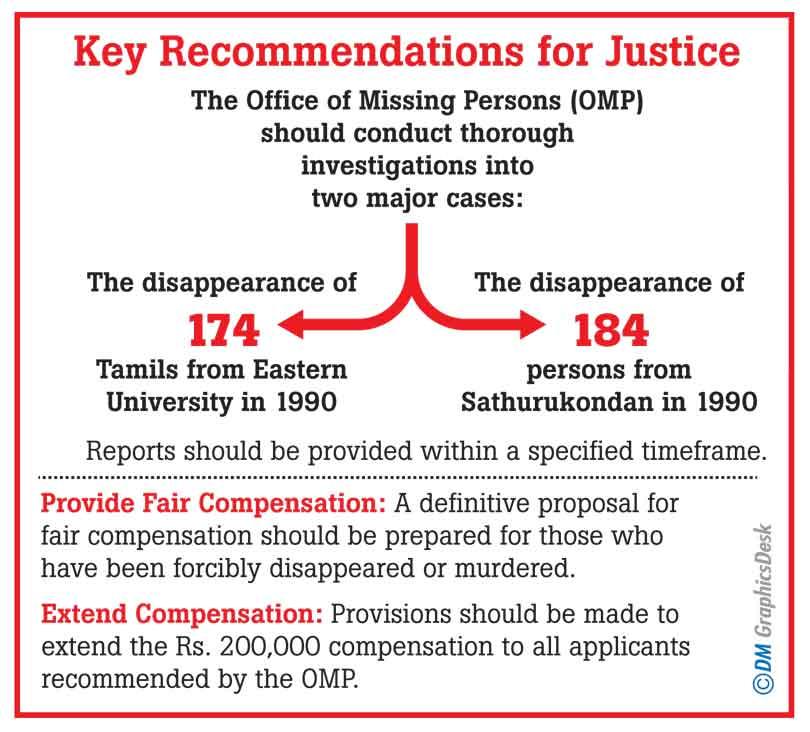

Key recommendations put forward by activists and families of disappeared for the successive government is as follows:

- The OMP should conduct investigations and provide reports within a specified time frame for at least two major cases: 1) The enforced disappearances and alleged massacre of 174 Tamils from the Eastern University on September 5, 1990, whose bodies remain unrecovered; 2) The abduction, disappearance, and alleged massacre of 184 persons from Sathurukondan on September 9, 1990.

- Investigate selected cases of surrenders in the South.

- Expedite ongoing cases of enforced disappearances in provincial courts.

- Complete all complaints currently received by the OMP to ensure the provision of Interim Relief for victims’ families.

Recommendations for Office of Reparations:

- Provide a definitive proposal for fair compensation to those who have been forcibly disappeared or murdered.

- Prepare provisions to extend the Rs 200,000 compensation, which is currently being paid, to all applicants recommended by the OMP.

Recommendations for Government interventions:

- Permit memorials for war victims of the North-East conflict, recognising the Tamil people’s right to remember their loved ones.

- Provide political, financial and other necessary support to maintain the functioning of institutions that are currently established (OMP and Office of Reparations).

- Enact legal provisions for the speedy conclusion of all proceedings related to disappearances pending in Sri Lankan courts.

- Support the “Sri Lanka Accountability Project (SLAP)” implemented by the Geneva Human Rights Council to achieve justice.

- Keep Sri Lanka on the agenda of the Geneva Human Rights Council, cooperating with and contributing to the UN process on this issue.

- Establish an independent prosecutor and a legal office dedicated to handling cases related to disappearances.

- Present a list of all those who surrendered at the end of the war and work to clarify their plight.

- Excavate and preserve mass graves that appear from time to time according to international standards, identify the victims, and take immediate steps to provide justice to their families.

With no acceptable explanation or information about the plight of their husbands, sons, and others, loved ones still harbour hope that they will return home someday. Many have lost their lives waiting, while the rest vow to fight until their last breath. Without closure, families remain unable to rest until they receive definitive answers, justice is served, and the perpetrators are held accountable.

“This is the plate my husband used to have rice in, and this is the mug my son used to drink tea from,” Jayanthi shared with the Daily Mirror, gently stroking a plate and mug displayed at the entrance of the Mihilaka Hall at the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall (BMICH) on August 30.

“This is the plate my husband used to have rice in, and this is the mug my son used to drink tea from,” Jayanthi shared with the Daily Mirror, gently stroking a plate and mug displayed at the entrance of the Mihilaka Hall at the Bandaranaike Memorial International Conference Hall (BMICH) on August 30.  Sri Lanka ranks 2nd in enforced disappearances

Sri Lanka ranks 2nd in enforced disappearances For decades, in Sri Lanka, enforced disappearances have been a tool used to suppress political dissent and combat ‘terrorism.’

For decades, in Sri Lanka, enforced disappearances have been a tool used to suppress political dissent and combat ‘terrorism.’ was passed, criminalising enforced disappearances. However, activists and families emphasise that enforced disappearances that occurred before 2018 cannot be prosecuted under this law.

was passed, criminalising enforced disappearances. However, activists and families emphasise that enforced disappearances that occurred before 2018 cannot be prosecuted under this law.  Echoes from the north

Echoes from the north government activities.

government activities.