Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The multi-day trawler carrying 115 people from Rohingya

Irregular migrants to Sri Lanka from Myanmar are currently held in Mullaitivu till the two governments decide on their futures

Representatives of the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka have requested an opportunity to monitor the detention conditions of the asylum seekers, but have been denied access

The present issue in Sri Lanka is of concern because a refugee situation is militarised without the presence of a neutral third party with expertise in refugee rights

The 103 individuals detained at the Air Force Camp in Mullaitivu cannot yet be classified as refugees

Since Sri Lanka isn’t a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, there is no judicial review of claims made by refugees in Sri Lankan courts

“There is still no basis to consider them as refugees yet. For now, this is regarded as a case of human trafficking. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been in contact with the Myanmar government, and the list of names has already been shared with them. We will follow the legal process, engage in discussions with the Myanmar government, and, at this point, are considering deporting them. Until then, they will be held in Mullaitivu and provided with all necessary facilities. We will take action abiding by international law,” stated Minister of Public Security and Parliamentary Affairs, Ananda Wijepala, when contacted by the Daily Mirror on December 29 for an update on the situation concerning the Rohingya refugees.

“There is still no basis to consider them as refugees yet. For now, this is regarded as a case of human trafficking. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been in contact with the Myanmar government, and the list of names has already been shared with them. We will follow the legal process, engage in discussions with the Myanmar government, and, at this point, are considering deporting them. Until then, they will be held in Mullaitivu and provided with all necessary facilities. We will take action abiding by international law,” stated Minister of Public Security and Parliamentary Affairs, Ananda Wijepala, when contacted by the Daily Mirror on December 29 for an update on the situation concerning the Rohingya refugees.

Attempts to contact Minister of Foreign Affairs Vijitha Herath and Chief Government Whip and Cabinet Spokesperson Dr. Nalinda Jayatissa were unsuccessful.

Attempts to contact Minister of Foreign Affairs Vijitha Herath and Chief Government Whip and Cabinet Spokesperson Dr. Nalinda Jayatissa were unsuccessful.

On December 19, a multi-day trawler carrying 115 people from Rohingya drifted towards the coast of Mullivaikkal in Mullaitivu. The boat had 103 individuals seeking asylum, alongside 12 persons who had initiated the journey. When the refugees were presented before the Trincomalee Magistrate Court, the 12 individuals were remanded, while the remaining refugees were ordered to be sent to the Mirihana Immigration Detention Centre. However, they were later detained at the Air Force camp in Mullaitivu, where they continue to be held.

Investigations into identities underway

The 103 individuals detained at the Air Force Camp in Mullaitivu cannot yet be classified as refugees and are currently regarded as irregular migrants, an official from the Department of Immigration and Emigration who spoke on condition of anonymity said.

The official stated that investigations are ongoing to verify the identities of these individuals. “Although they provide their names, some change them from time to time, so we must rely on legal documents to confirm their identities. The Police are conducting a thorough investigation, and once it is complete, we will assess the reasons for their arrival. All other matters will be addressed subsequently,” the official explained.

When asked by the Daily Mirror if the individuals would be transferred to the Mirihana Immigration Detention Centre as initially ordered by the Magistrate, the official claimed no knowledge of such information.

This journalist also inquired about officials from the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL), who wished to monitor the detention conditions of the asylum seekers, being denied access to the Air Force Camp. The official clarified that only investigation officers are currently permitted access, and others must obtain special approval from the Controller General of the Department of Immigration and Emigration.

On December 27, 2024, the HRCSL wrote to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake regarding the incident, emphasising that according to section 11(d) of the HRCSL Act, No. 21 of 1996, the powers and functions of the Commission extend not only to Sri Lankan citizens, but to ‘any person’ detained within Sri Lanka. Therefore, the Commission has the statutory authority to access the said Air Force Camp and monitor the detention conditions of all asylum seekers, including the children present,” the HRCSL said in a statement.

On December 27, 2024, the HRCSL wrote to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake regarding the incident, emphasising that according to section 11(d) of the HRCSL Act, No. 21 of 1996, the powers and functions of the Commission extend not only to Sri Lankan citizens, but to ‘any person’ detained within Sri Lanka. Therefore, the Commission has the statutory authority to access the said Air Force Camp and monitor the detention conditions of all asylum seekers, including the children present,” the HRCSL said in a statement.

Initially, the HRCSL was asked to submit a written request to the Controller General of the Department of Immigration and Emigration to obtain access. However, an Assistant Controller General of the Department had later informed the HRCSL that permission must be obtained from the Minister of Public Security and Parliamentary Affairs, Ananda Wijepala.

In its letter, the HRCSL urged the President to issue appropriate directives to ensure that relevant institutions facilitate access to the asylum seekers, reaffirming its statutory obligations to examine their detention conditions.

‘Refugees Are Not Criminals’

|

Minister of Public Security and Parliamentary Affairs, Ananda Wijepala

|

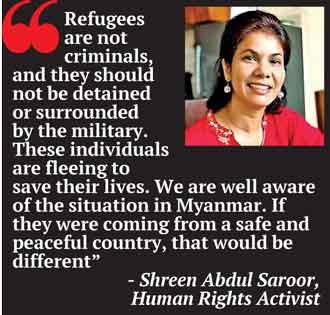

“Often, people flee their countries due to atrocities committed by security forces, whether Army, Navy, Air Force, or Police—forces carrying guns. When they come to another country and there is no neutral party, like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or civil society, they are again subjected to processes involving the same type of security apparatus—uniformed men with guns, whose attitudes are often negative towards refugees and who lack an understanding of refugee rights. Refugees are not criminals, and they should not be detained or surrounded by the military. These individuals are fleeing to save their lives. We are well aware of the situation in Myanmar. If they were coming from a safe and peaceful country, that would be different. But they are coming from a very unsafe environment,” emphasised Human Rights Activist Shreen Abdul Saroor.

Saroor added that refugees encountering armed and uniformed personnel can be retraumatized, as it mirrors the experiences they endured in their home countries, which they fled due to fear. “This group consists primarily of children and women, while our forces are predominantly men. This is problematic because atrocities were committed against women and children during Sri Lanka’s war, with no accountability. To have these same forces overseeing vulnerable groups like women and children is a concern because they are not trained for this role. There is a pregnant woman, a newborn baby, elderly persons, and two physically challenged individuals among the refugees. How equipped is our military system to care for them? What do they know about disability, malnutrition, or childcare? These are critical issues. When refugee situations are militarized without a neutral third party with expertise in refugee rights, their well-being is jeopardised. The presence of the UNHCR in Sri Lanka is crucial,” she asserted.

With the UNHCR transitioning to a liaison office model in Sri Lanka as of December 31, 2024, the future of refugees has become increasingly uncertain. “Without the UNHCR’s active presence, nobody will know what happens to refugees. Even if they are deported, we will have no information about the conditions under which they are sent back. This is why we need the UNHCR to be involved,” Saroor stressed.

However, Lakshan Dias, a renowned refugee and Human Rights Lawyer, underscored that despite the UNHCR operating as a one-person liaison office in Sri Lanka from 2025, it continues to accept refugee applications and issue recognition papers with support from the UNHCR Bangkok hub. “These individuals can still apply to the UNHCR Colombo office to seek asylum. There is no obstacle to that process,” he clarified.

Can the refugees be deported by law?

|

Air Force Media Spokesperson, Captain Eranda Geeganage

|

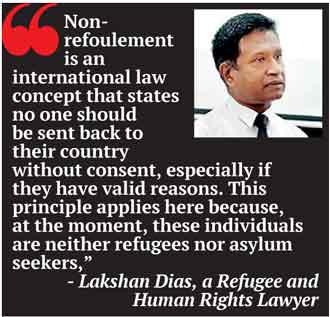

The Daily Mirror also inquired from Dias, a lawyer with nearly 20 years of experience in refugee cases, to understand whether the recently arrived refugees can be deported, as implied by Minister Wijepala. Dias highlighted that although Sri Lanka is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, the country is bound by international law to ensure that they follow a due process.

“Non-refoulement is an international law concept that states no one should be sent back to their country without consent, especially if they have valid reasons. This principle applies here because, at the moment, these individuals are neither refugees nor asylum seekers. They were intercepted, apprehended, and brought ashore by the Navy and claim to be heading to another destination to seek asylum. They fall under the broader ambit of refugees and asylum seekers. However, they have not yet sought asylum with either the Sri Lankan government or the UNHCR,” Dias explained.

He further elaborated that the Rohingya people from Myanmar’s Arakan province face severe repression by their government, giving them a well-founded fear—one of the key criteria for seeking asylum or refugee status.

Dias noted that governments cannot deport individuals arbitrarily, as seen in Australia’s treatment of Sri Lankans arriving by boat. “Once they reach a border seeking asylum, even if it creates an influx, they cannot simply be sent back. That is prohibited. Under customary international law, Sri Lanka has an obligation to look after these individuals. Even Sri Lankans attempting to reach Australia must undergo due process. However, Australia often moves such individuals to remote islands or offshore facilities where they hear the case and state that they found the story not credible and hence fail the case; then they allow an appeal and then say that the appeal also failed and hence deport them. This is not a democratic process,” he said.

He emphasised that Sri Lanka, as a democratic nation, must allow refugees to go through proper legal procedures. “Since we are not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, there is no judicial review of their claims in Sri Lanka’s courts. Refugees can apply for status or seek asylum under the UNHCR. It is crucial that the government ensures these individuals are provided with the opportunity to do so, adhering to international law,” Dias said.

|

‘No space for refugee abuse at Air Force camp’-Captain Geeganage “Ten police constables are stationed at the location, along with four police women assigned to address women’s matters. There is no room for abuse as all necessary security measures are in place. The four policewomen were deployed following a request from the Air Force,” emphasised Media Spokesperson for the Air Force, Captain Eranda Geeganage on December 29. Separate accommodations for men and women, including individual sanitary facilities, have been arranged, according to Capt. Geeganage. “All medical needs are being attended to, and so far, the refugees appear to be in good health. In case of an emergency, we have been directed by the Department of Immigration and Emigration to take them to the Mulliyawalai Hospital,” he added. When asked by the Daily Mirror about the duration of the refugees’ stay at the Air Force camp in Mullaitivu, Capt. Geeganage stated that he was not informed of such. “Administrative matters are handled by the Department of Immigration and Emigration. Our role is limited to providing accommodation and meals,” he clarified. According to data from the Air Force, the group of asylum seekers consists of 24 males under 16 years, 27 females under 16 years, 24 males above 16 years, and 28 females above 16 years. Capt. Geeganage also confirmed that there was one pregnant female among the group. |

The UNHCR Process

Regardless of whether these individuals have formally sought asylum, they are still considered asylum seekers, and the government must provide official permission for the UNHCR to engage with them, emphasized Dias. “It is a human right of the Rohingya people to have access to the UNHCR. Once the UNHCR meets them, it can process their request to seek refugee status,” he stated.

Dias pointed out that the UNHCR might refuse to conduct the Refugee Status Determination (RSD) process within a security camp, citing it as an unsuitable environment. This has happened in previous cases. “The UNHCR may request to move the individuals to an independent location for interviews before sending them back to the center. Legally, the UNHCR is obligated to listen to each person’s case, including those of children. They may require assistance from the UNHCR Bangkok hub for this process,” he explained.

If the UNHCR determines that the refugees have a well-founded fear of persecution and qualify as asylum seekers, it must inform the Sri Lankan government under the 2006 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the two entities. This would allow the refugees to integrate into society. Once the UNHCR issues recognition papers, the refugees can no longer be confined, Dias stressed.

However, Dias noted that the Government of Sri Lanka has previously been reluctant to allow Rohingya refugees to live freely within the society. In 2012 or 2013, about 70 Rohingya refugees were placed in a facility with high walls and barbed wire. They were allowed to leave in the morning, but had to return by night. If they failed to do so, their absence was recorded, and action was taken. “This is very wrong,” Dias remarked, warning that a similar situation could occur with the recently arrived Rohingya refugees, even if the UNHCR gains access and provides recognition.

Dias added that if the government denies UNHCR access, it still cannot keep the refugees in an army or security force camp. “They must be moved to immigration detention centres in Mirihana or Welisara,” he concluded.

Can refugees be held in military camps?

Under international law, or international understanding of law, immigration violations are considered civil offenses, not criminal ones, explained Dias. Hence, such cases must be treated accordingly. Since these individuals are foreigners with visa-related issues, they cannot live publicly without proper documentation. Therefore, they should be placed in an immigration detention centre.

“As far as I know, this matter was initially presented to the magistrate, who ordered the refugees to be sent to the Mirihana detention centre. However, I am unsure how that order was later changed. It could have been a temporary measure for one week due to practical reasons, but it should not become a long-term solution. These individuals must be sent to an immigration detention centre as per normal practice. Holding them in a military camp exposes them to potential abuse—a risk anywhere in the world. For the past 18 years, the standard legal procedure in Sri Lanka has been to place such individuals in immigration detention centres,” Dias stated.

He also highlighted Sri Lanka’s own history with refugees. “This government includes members who were refugees in other parts of the world. We have had those in previous governments who were refugees in other countries. For the past 50 years, our country has faced conflict, producing nearly one million refugees from all communities who sought asylum abroad. These refugees have contributed billions of dollars to Sri Lanka, supporting their families back home. As a country, we have benefited greatly from the UN and the internationally recognized refugee system. We, therefore, have a moral obligation to assist these individuals. We are only talking about around 100 people here,” he said.

Dias emphasised that Sri Lanka must not forget its history. “When others face similar situations, we cannot turn a blind eye and say we have too many problems to help. Our experience as a nation compels us to uphold these responsibilities,” he concluded.