Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

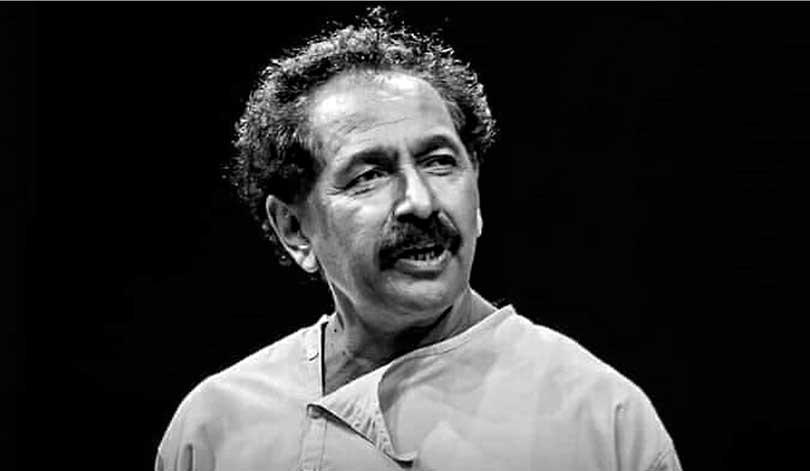

He was Jayalath to some, Dr Manoratne to others, and Mano to us.

He was Jayalath to some, Dr Manoratne to others, and Mano to us.

When television came to Sri Lanka in the 1980s, Jayalath Manoratne was one of many stage actors who made the transition to the small screen. Almost all the tele-series he took part in were sitcoms, and even when they were not – like Kande Gedara and the enormously popular Doo Daruwo – you could sense something of the comic in him.

Jayalath had been in films before – you’ll remember him from Handaya – but television became his preferred medium outside the theatre, just as it did for Suminda Sirisena, Manike Attanayake, Vijaya Nandasiri, and Mercy Edirisinghe. They came from the same generation: All of them had been born between 1946 and 1948, and all of them had begun their careers under a thespian. Mercy was the first among them to depart, in 2014, and three years later Vijaya followed. Two days ago Manoratne followed suit. It is difficult to think they’ll be gone for good.

I haven’t been to many plays, and I’ve missed much of the work that defined the man, but if you were in Sri Lanka it was impossible to miss him. He was everywhere, and in many ways, he was everywhere with us.

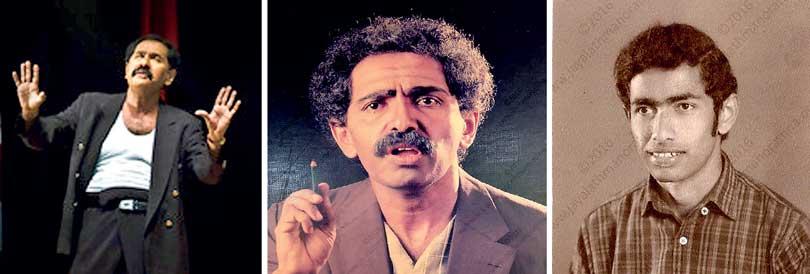

What struck you about him at first were his looks – the bushy hair, the thick eyebrows, the pinched up face, the sharp nose – which congealed to a face that could jump from boisterousness to self-doubt to arrogance within a matter of seconds. A face like that didn’t come often to the local screen, and theatrical as it was, it came naturally to him.

Like Joe Abeywickrema, Jayalath was never a hero, and like Joe, his face could convey a myriad of impressions which told us a lot more about the character than what he was made to speak.

Even on that occasional outing when he was cast as a hero – like the coach in Goal – he could never abandon that dexterity. He could leap from one rock to another and just as soon come back. And for over 30 years, that’s what he did.

To locate him against the wider cultural landscape of the country is difficult. Manoratne came at a time when the first generation of thespians-turned-film-stars had established themselves; in particular, Tony Ranasinghe and Henry Jayasena.

The latter emerged from an intermediate, bilingual, suburban milieu for which the administrative service remained a goal. On the other hand, thanks to the changes wrought after 1956, a new generation hailing from a more rural background found in the university a path through which they could unleash their creativity. It was at this point that Manoratne entered Peradeniya.

Western culture being cut off from his milieu, they discovered it in the University. Later, they would incorporate Western Theatrical forms with local theatre, though Manoratne didn’t try his hand at it: His plays, until the end, retained a distinctly local flavour and idiom.

He began his stage career with Premati Jayati Soko and Vessantara, both by Sarachchandra, the latter being his final work. He came to the movies at the same time his contemporaries did: Manoratne with Handaya and Tilaka saha Tilaka, Suminda Sirisena with Duhulu Malak, Vijaya Nandasiri with Nedayo and Hingana Kolla, and Mercy Edirisinghe with Diyamanthi and Palagetiyo.

Then television happened, and the roles kept coming to him: Bodima, Kande Gedara, Gamperaliya,Madol Doowa, Sedona, and Doo Daruwo. We saw him later in Gal Pilimaya saha Bol Milimaya, Sakisanda Eliyas, and Deiyyo Saakki (where he was paired with Suminda Sirisena and Sriyantha Mendis). His movie credits were insignificant at first – a journalist in Saptha Kanya and Sisila Gini Gani – but later he got to the top: Most memorably as the monk in Sooriya Arana. Unlike Dharmasiri Bandaranayake, another contemporary, he didn’t abandon the cinema, yet he returned to the theatre and remained in it: As an actor, a writer, and a teacher. He devoted all the time he had and could get, to the stage.

What could explain his incredibly fertile career? Certainly, not his looks or face: He was not notable in the same vein as, say, Sriyantha Mendis and Kamal Addaraarachchi were.

Thin, lanky, rather unsure of himself, people could not have accorded to him the kind of status they had readily accorded to his contemporaries: if his roles from the 80s could all be summed up, they could thus only be described as un-extraordinary.

In Kande Gedara he’s the richest son of a fairly well off rural family, the two elders of which leave after the mother has an argument with a daughter-in-law who remains in their ancestral home. Manoratne is the only son of theirs who’s prospered: Well educated, working at a top company, he lives in a posh comfortable Colombo house. The son and daughter are typical specimens of the post-1977 Colombo middle class: the son watches Bruce Lee films and the daughter dotes on Michael Jackson. It’s a chaotic family, neither here nor there, and the wife, played by Veena Jayakody, doesn’t take too well to her in-laws moving in; the culture shock, a frequently depicted theme in Sinhala television serials during that decade, proves to be too much.

Amidst these confusions, Manoratne tries his best to resolve the differences, and fails; when he’s finally pushed over, he lashes out – as he does when his daughter half-mockingly asks her grandparents as to whether they’ve heard of Jackson.

If Suminda Sirisena in almost every role he got played variations of the reasonable, rational-minded protagonist, and if Sriyantha Mendis played variations of the leering pretender (the contrast between them comes out in Asalwasiyo), Manoratne in this period almost always got to play that bewildered, confused everyman: he’s caught up in the action, but all too often he’s also distanced from it. In Bodima he’s an English teacher – the only tenant in his annexe who can understand that language – but though he’s obviously got a back story he never gets us interested in it.

He has his odd mannerisms: He counts numbers when he sneezes and he reverts to English even when he knows no one understands him. Then in two episodes, we see his other side: His wife pays a visit, and so does his teacher. Compared to the other prodigals in the annexe – what a colourful set they were – he seems quite normal, but just as you lose interest in him, he reveals himself. If you see variations of this in his later roles – as Jinadasa in Gamperaliya, for instance – it was partly owing to his figure. Later, when he grew out of that figure and became more burly and assertive, he changed.

Gamini, Tony, and Joe were at the height of their careers when they were in the prime of their youth. This was true even of Vijaya Kumaratunga.

But the actors who made their way to the movies through television had to wait until much later to get top billing in the cinema, and Manoratne was no exception. Of his movie performances, the ones that really counted were, in that sense, few and far in between, because he was notoriously selective. Sriyantha Mendis and Suminda Sirisena, when they were not indulging in melodrama, indulged in political satire; Manoratne wasn’t like that. And I think I know why: He was too involved in the theatre to think of the cinema as anything other than an occasional diversion.

In the end, what might have prevented him from rising to the top in the industry got him top billing. He could get theatrical, unforgivably so, when the sequence demanded that he tone down. He did intermittently tone down: In Sooriya Arana, opposite Jackson Anthony’s raving Veddah, he’s quite nondescript, so much so that when he loses his temper and lashes out, the film jars; the fact that I remember these sequences more vividly than I do the veddha’s own outbursts indicates that the contrast between his usual demeanour and his tempestuous fits couldn’t be resolved.

At that point, moreover, Manoratne stopped taking on unlikeable roles, and in the last decade of his career, he never played the antagonist. This was in contrast to not only Sriyantha and Suminda, but also Vijaya Nandasiri.

Sumitra Peries once told me that when they were shooting a sequence in Loku Duwa in which Gamini Fonseka waits for his daughter at the Kalutara Bodiya and plays around with his lighter, she couldn’t stop the camera: “I wasn’t sure whether he was acting or not.”

There’s a sequence in Ho Gana Pokuna in which Manoratne poses for a photograph for his bus driver’s license, and he fails: the photographer (Whom we never see) commands him to smile widely, look up straight with his chin, then not so up, lower the chin, and so on. I’m not sure whether the camera kept rolling or whether Indika Ferdinando wasn’t sure about the acting.

I wouldn’t be surprised if he wasn’t: that sequence, in all its terseness, takes your breath away. But it’s not improvisation, and the contrast with Gamini’s acting comes off: even at his most flippant, Manoratne remained within the bounds of the theatre, and it showed. In that sense, he was in, and of, the theatre. Even in front of the camera. And right until his death.