Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

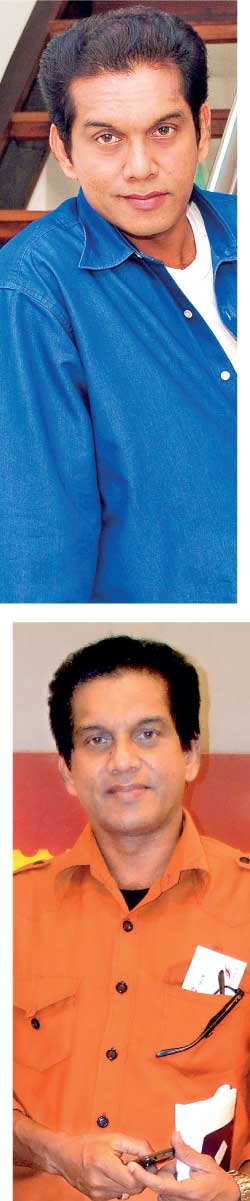

When Kamal Addararachchi struts or strolls into a sequence of a film, he is deliberately flamboyant, because he wants to let us know he is THERE. But his flamboyance is not what vindicates him, because for a career spanning 35 years 35 films and roles are all he got, and if flamboyance figured in there he would have got more, much more, than what he ended up with. Within a limited canvas Kamal thus gives the best he’s got. He is choosy, more than a little selective and picky, so the few performances we remember with almost sensuous excitement – the hero of Saptha Kanya and Julietge Boomikawa, the prodigal son of Loku Duwa and Awaragira – we remember quite well. Kamal’s face in this sense has been his biggest strength, or at least one of his biggest strengths, because it can convey infatuation and dislike. That he has teetered between two broad kinds of roles – as mentioned before, the lover and the prodigal son – and variations thereof speaks volumes about the fact that to be a flamboyant performer isn’t necessarily to have a diverse range.

When Kamal Addararachchi struts or strolls into a sequence of a film, he is deliberately flamboyant, because he wants to let us know he is THERE. But his flamboyance is not what vindicates him, because for a career spanning 35 years 35 films and roles are all he got, and if flamboyance figured in there he would have got more, much more, than what he ended up with. Within a limited canvas Kamal thus gives the best he’s got. He is choosy, more than a little selective and picky, so the few performances we remember with almost sensuous excitement – the hero of Saptha Kanya and Julietge Boomikawa, the prodigal son of Loku Duwa and Awaragira – we remember quite well. Kamal’s face in this sense has been his biggest strength, or at least one of his biggest strengths, because it can convey infatuation and dislike. That he has teetered between two broad kinds of roles – as mentioned before, the lover and the prodigal son – and variations thereof speaks volumes about the fact that to be a flamboyant performer isn’t necessarily to have a diverse range.

And being flamboyant has its pitfalls, moreover: if you don’t evoke enough interest in the audience, you will fail them, no matter how many charades and pageants you summon with your physique. That’s why his lesser supporting performances don’t stand out – whether as Chandrasoma in Kaliyugaya or as the political son in his debut film, Sagarayak Meda – not because he doesn’t try or retain enough conviction, but because he’s so apparent and outlandish that we need him to be the star of the vehicle he is in, and in these two films he is not that kind of star. We don’t care whether we root for him or oppose him – and he has acted in many movies which have him as a dislikeable son or sister or wayward womaniser – but we do care whether he stands out. By standing out, he defines himself, not in relation to his other characters and how they regard him, but by himself. He operates from a world of his own.

Kamal’s debut as a thespian was aboard a satirical play titled Ane Ablick, first performed in Colombo in 1978. What happened next was in one sense inevitable: a film producer, having seen him act, got him to meet another Fonseka, no less a figure than Gamini Fonseka, over a film that the two of them were planning on doing

Kamal is serious about his standards and the roles they land him. Apart from one film (each) by Roy de Silva, Sunil Soma Peiris, and Anton Gregory, he hasn’t exactly moved into the mainstream cinema. All he wants, in that sense, is to be and to remain pure and pristine, a tough enterprise in a country and industry where popular audiences tend to shirk the halls if those halls aren’t screening a product from that mainstream cinema. The fact that we endear ourselves to him, no matter what kind of movie he’s in, attests to the fact that he is indifferent to this reality in our industry, yet triumphs. We need to see him, and in the end, we measure him up by the strut, the tones, the accent, the inflections, and everything else that he has nurtured and built for himself.

Addararachchige Gunendra Kamal was born on February 5, 1962 to a gem merchant family in Ratnapura. He was sent to Wesley College, Colombo, where he developed an interest in the arts: among other activities, he had been the drummer in a five-piece schoolboy band called Cat’s Eyes. By his own confession though, neither the theatre nor the cinema held much promise for him. By the time he entered Grade Five, he began acting in dialogues-driven, serious productions, but for his shift to the performing arts, he had to have a guiding figure, a figure of destiny. That figure of destiny was Gamini Samarakoon, who taught him drama in Grade Nine. As Kamal told me around two years ago, “More than drama, he taught me miming. That marked my first brush with the medium.” With Samarakoon came a horde of other influences: Nimal Fernando, a primary class teacher, Heig Karunaratne, who taught him not just drama but also music as he went up, and Shelton Weerasinghe, the Principal at Wesley who did much to uplift the arts.

The liaison between his school and the outside world, incidentally, was Karunaratne, who advised Kamal to apply for an acting course he had come across in the newspapers. That course was to be conducted by a leading theatre practitioner named Dr. Nobert J. Mayar, from Germany, and was sponsored and organised by the International Theatre for Children and Youth (ITCY). It would span three months and some workshops, almost all of which Kamal enthusiastically took part in. “I never regretted Mr. Karunaratne’s request. I obliged and I have since looked back with unyielding gratitude.” The three-month course got him to meet three people who would figure in his career, as colleagues: Jayantha Chandrasiri and Sriyantha Mendis. All three had, moreover, been tutored by another leading figure: Dr Salamon Fonseka, according to Kamal the first Sri Lankan to have a PhD in drama and theatre.

We need to see him, and in the end, we measure him up by the strut, the tones, the accent, the inflections, and everything else that he has nurtured and built for himself

All that remains in my mind of Fonseka, regrettably, is the image of him as the manservant to the hamu mahaththaya in Parakrama Niriella’s Siri Medura, but the truth of the matter is that he was more, much more, than a supporting player in the occasional film. Fonseka, those who studied under him (and there were quite a few: Sriyantha, Prageeth Ratnayake, Palitha Silva, and an acquaintance of mine who doesn’t act but knows the field well) will attest, did what no one, not even Gunasena  Galappaththy or Dhamma Jagoda before him did: bring method acting to Sri Lanka through a series of structured, academic courses designed to evince Stanislawsky’s founding principles. While Jagoda and Galappaththy had learnt of the Method in America, Fonseka had gone to Europe itself. No doubt Kamal was enriched by his encounters with the man.

Galappaththy or Dhamma Jagoda before him did: bring method acting to Sri Lanka through a series of structured, academic courses designed to evince Stanislawsky’s founding principles. While Jagoda and Galappaththy had learnt of the Method in America, Fonseka had gone to Europe itself. No doubt Kamal was enriched by his encounters with the man.

Kamal’s debut as a thespian was aboard a satirical play titled Ane Ablick, first performed in Colombo in 1978. What happened next was in one sense inevitable: a film producer, having seen him act, got him to meet another Fonseka, no less a figure than Gamini Fonseka, over a film that the two of them were planning on doing. The film, which would mark Gamini’s fourth foray into the world of directing, was Sagarayak Meda, and in it the young Kamal would be featured as the Marxist, sloganeering son to the apolitical hero (played by Gamini himself). He was, needless to say, perturbed but also excited: perturbed, because he hadn’t opened himself to the cinema and because he knew that his parents would not allow him there; excited, because the next step after stage dramas for a budding actor was the film industry.

In the end, he lied to his mother and father. By the time he was caught, red-handed, and reprimanded, Sagarayak Meda was already being screened in the theatres. From that point on, he revelled in playing out two distinct kinds of characters: the everyman bewildered by fortuitous circumstances (Saptha Kanya, Guerrilla Marketing), and, as I pointed out at the beginning of this piece, the thoughtless, callous, cruel prodigal son. As the former, he compels our empathy and makes us want to win; as the latter, he gets us to envision his own end, as with both Loku Duwa (where he’s beaten to a pulp by Gamini Fonseka) and Awaragira (where he is stabbed to death in the end). No matter what his performance is, I sense a subtle intermingling of goodness and badness, so much so that even when he teeters to one side of that big divide, he retains enough from the other side to keep himself from sliding down that forever easy path of being a stereotyped character actor.