Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

- The human condition he depicts may be harsher, but his characters find a way out...

- In this portrait, Bijon draws upon a tradition whereby the best teachers in the newly formed nation were Hindus

- Ray and Bijon have common Bengali culture

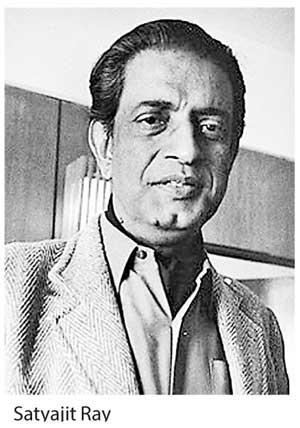

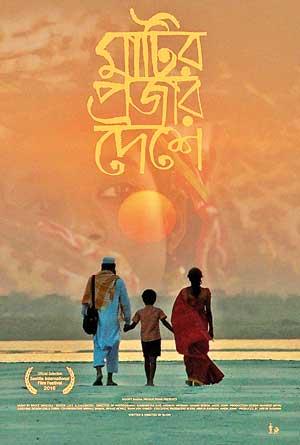

We know about Indian cinema, but Bangladesh remains a dark horse as far as its movie industry is concerned. The annual Bangladeshi film festival held in Colombo (Scheduled for March 2020) will go some way to put this right. But a screening of Kingdom of Clay Subjects by filmmaker Bijon Imtiaz (Bijon) at the Bangladeshi High Commission in Colombo ushered the viewer into a lyrical cinematic tradition, whose roots lie with cinematic greats such as Satyajit Ray. As one watched this 2016 movie, the viewer was instantly transported into the cinematic language of subdued emotion that characterizes the Bengali master’s cinema.

festival held in Colombo (Scheduled for March 2020) will go some way to put this right. But a screening of Kingdom of Clay Subjects by filmmaker Bijon Imtiaz (Bijon) at the Bangladeshi High Commission in Colombo ushered the viewer into a lyrical cinematic tradition, whose roots lie with cinematic greats such as Satyajit Ray. As one watched this 2016 movie, the viewer was instantly transported into the cinematic language of subdued emotion that characterizes the Bengali master’s cinema.

Even the film’s timeframe looks deliberately ambiguous. Bijon’s village looks very much like Ray’s, and props such as motor vehicles or street lights which would give the viewer a clue as to the period are conspicuously missing – what we see is a standard bicycle which hasn’t changed much since its inception.

Even the film’s timeframe looks deliberately ambiguous. Bijon’s village looks very much like Ray’s, and props such as motor vehicles or street lights which would give the viewer a clue as to the period are conspicuously missing – what we see is a standard bicycle which hasn’t changed much since its inception.

Ray was Indian. Bijon is Bangladeshi. One was Hindu, the other Muslim. But what they have in common, apart from a similar cinematic idiom, is Bengali culture, the feeling of belonging to the same roots and traditions.

After viewing Bijon’s debut feature, it becomes clear that Bengali culture, or the feeling of being Bengali, overrides being Hindu or Muslim or anything else. Essentially, the culture which nurtured and inspired Rai also inspires Bijon.

Like in Rai’s debut feature Pather Panchali, in Bijon’s debut movie two children dominate the screen and loom larger than life in our minds.

Ten-year-old Jamal (Mahmadur Anindo) and his friend Lokkhi (Sheuly Akther Jarin) are close friends. Lokkhi looks bigger, but we are told they are the same age. Fatherless, Jamal dreams of going to school, but his hardworking mother Fathima says he would be better off working and earning a living.

The idyll of these two children is shattered when Lokkhi’s father, a poverty-stricken farmer, decides to marry her off as a child bride. But he is unable to give part of the promised dowry (a bicycle and a clock), and the father-in-law threatens to send her back if the promise isn’t kept.

The dilemma is solved when Lokkhi runs away while being carried to her new home. The filmmaker says this is based on a personal memory when his grandmother ran away from a child marriage situation.

At every point, the director emphasizes the poverty which defines the lives of his characters. But he does so elegantly, without sentimentality and without laying it on too thick – typical Ray approaches to storytelling.

But he takes a radical turn halfway, unthinkable if we strictly follow the Ray idiom, by introducing a menacing element – the ordeal of Fathima when she finally consents to take Jamal to  school, and the ensuing revelation that she is a former sex worker.

school, and the ensuing revelation that she is a former sex worker.

Bijon pays homage to Ray, but his story is significantly different from that of Pather Panchali despite some striking similarities. Durga and Apu, the two siblings of an impoverished priest, are raised at least by their struggling mother when her husband leaves the village looking for work.

But the world of brother and sister is more innocent than that of Jamal and Lokkhi, although Durga steals from

her neighbours.

The black and white grain fields they play in, the mise-en-scène of that celebrated shot when the two siblings run towards a distant train, are strikingly similar to the vivid Yellow Orche landscapes that are playgrounds to Jamal

and Lokkhi.

But the latter’s world is far more troubled despite the surface beauty their eyes feast on. True, Durga’s end is tragic as she dies of a fever. But that fever is caused by rain. The ending, when her father returns home to take his wife and daughter away from the village, again resonates in the positive way Bijon’s movie ends.

The human condition in the world he depicts may be harsher, but his characters, just like Ray’s, find a way out of seemingly impossible situations in the end.

The screening was followed by an online discussion with Arfur Rahman, one of the movie’s co-producers, via the High Commissioner’s smartphone.

It was enlightening as to how, in such a cash-strapped country, the new generation of filmmakers manages to make feature films. Many are expatriates working in Europe and the United States. The Kingdom of Clay film project was started with a budget of US$ 20,000.

It was enlightening as to how, in such a cash-strapped country, the new generation of filmmakers manages to make feature films. Many are expatriates working in Europe and the United States. The Kingdom of Clay film project was started with a budget of US$ 20,000.

Bijon is the first Bangladeshi filmmaker to graduate in film production and directing from the University of California, Los Angeles.

The movie did well outside Bangladesh, having its world premiere at 42nd Seattle International Film Festival and bagging the best film award at the 7th Chicago South Asian Film Festival.

But what was the reaction in Bangladesh for this movie with what might easily be perceived as a controversial storyline, with the village Imam coming to the rescue of Fathima and Jamal when they risk public censure and being driven out of the village?

According to Arfur Rahman, the movie was received very well in Bangladesh, with no conservative backlash. This is very significant to the filmmaker and his backers in view of the violent reaction to Bangladesh’s blogging community in 2012 when a number were attacked and killed by religious conservatives. Bijon too belonged there.

But the Imam in this movie does not portray any criticism of Islam. He is a moderate, whose benign, smiling face and gentle manner contradicts the image of violent Islam that is prevalent in the non-Islamic world. But he is also willing to go against convention. He is essentially a loner who believes in justice for the struggling individual and is willing to give Fathima a fair hearing when an impromptu village inquisition is all bent on branding her as immoral.

The filmmaker emphasizes the tolerant aspects of Bengali culture. The headmaster of the school where Jamal tries to enrol is Hindu, but it’s his Muslim clerk who makes trouble for Fathima and her son.

In this portrait, Bijon draws upon a tradition whereby the best teachers in the newly formed nation were Hindus.

The music was done by Bruce Driscoll, an American, who creates a richly textured score with hints of fusion that works harmoniously with the lush colour tones of the movie’s landscapes as filmed by cinematographers Ramshreyas Rao and Andrew Wesman.