Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Political splits are inevitable. They happen and are easy to predict. The reasons for those splits, however, are difficult to ascertain. More often than not, feel-good, self-righteous, chest-thumping statements about democracy and good governance are made to the public. The public, for their part, believes these to be the causes for those splits, when the reality may be different. After all, who can now deny that the ruckus over good governance was a cover for the personality clashes that led to the defections of so many parliamentarians? Who cannot now trace Duminda Dissanayake’s decision to defect from the Rajapaksas to the Rajapaksas’ acts of snubbing his father?

governance was a cover for the personality clashes that led to the defections of so many parliamentarians? Who cannot now trace Duminda Dissanayake’s decision to defect from the Rajapaksas to the Rajapaksas’ acts of snubbing his father?

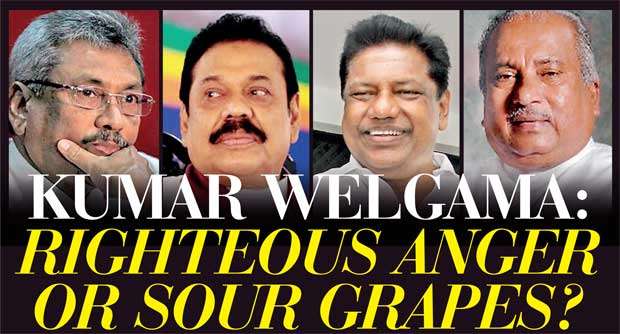

The bottom line is that when it comes to defections like this, there are always distinctions made in public between righteous anger (provoked by the excesses of a ruling coalition) and sour grapes (provoked by the ruling coalition snubbing them). Such distinctions go a long way in painting the defectors as decent, just, and untainted by scandal. When, of course, the truth may be completely different.

The Joint Opposition is more than three years old. The Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) is now almost two years old. The latter was an offshoot of a party, established in 2000, that had failed to garner much support: the Sri Lanka Jathika Peramuna (SLJP). The definitive precursor to the Pohottuwa, the SLJP had made waves as a political party with its own platform and manifesto, even campaigning at the 2015 election alongside a plethora of small time, independent candidates. Wimal Geenage, the leader of the party, who was probably (though we can never be sure) installed as a Rajapaksa Proxy at the elections (for the record, he emerged last, with a grand collection of 1,826 votes or 0.02% of the total number), raised speculation as to who would “take over”. When G. L. Peiris took over with the Joint Opposition, the SLJP’slogo, a cricket bat, was changed to the now instantly recognizable flower bud. Much like Sarath Fonseka filing nomination papers from an unknown party linked to the Democratic United Front (DUF), then, the SLPP was a product of an unknown party, of vague political affiliations.

"The definitive precursor to the Pohottuwa, the SLJP had made waves as a political party with its own platform and manifesto, even campaigning at the 2015 election alongside a plethora of small time, independent candidates"

It was also a product of a shifting array of ideologies. Broadly, these are of two types. On the one hand, there are those who wish to see MR return. On the other hand, there are those who wish to see the Rajapaksas return. Yes, there is a clear difference. The one has hedged its bets on the man behind the movement, the other on the culture of nepotism he is said to have institutionalized during his term. No, it’s not easy to distinguish between the two. Where would MR be without his family, after all, and where would that culture of nepotism be without him? When the SLPP was begun, the Rajapaksa Restoration Project centred on MR. Supporters wanted him to come back. Gotabhaya and Basil, while not on the sidelines, were not a primary concern. The reason was obvious: Basil had, in popular opinion, had a history of shifting political loyalties (he abandoned the SLFP during the eighties), and Gotabhaya held a dual citizenship. For them to win big, a massive campaign had to be launched to market their “winnability”, Gotabhaya on the basis of his term at the Urban Development Authority (UDA) and Basil on the basis of his skills in “getting things done” outside Colombo (an ability that once earned him the unlovely sobriquet “Mr. 10 Percent” from Chandrika Kumaratunga). Kumar Welgama is not the first politician to harbour reservations about the trajectory of the SLPP in this respect. If rumours are true, such reservations have been harboured by other party firebrands, even the likes of Wimal Weerawansa and Gamini Lokuge. But Welgama is the first to come out publicly with his disenchantment.

The statements he has made at rallies organised by the SLPP are revealing. He has claimed that he would not be supporting a candidate other  than “a democratic leader”, that this extends even to the Rajapaksa family, and that the candidate the party fields in 2020 will have to be “at least a Pradeshiya Sabha member”. That last insinuation makes it clear that he is not happy with Gotabhaya Rajapaksa becoming the candidate. The reasons he gives are, while not vague, nevertheless complicated: he is for freedom and democracy, he is against nepotism, and he opposes racism. The racism charge fits in neatly with the UNP’s image of Gotabhaya as a Muslim bashing opportunist, an image borne more than anything else out of a photograph taken of the man and Gnanasara Thera together. The nepotism charge and harangue against the man’s democratic credentials (or lack thereof) fit in neatly with the UNP’s ‘white van’ rhetoric against his family. In other words, Welgama is subscribing to the propaganda those opposed to the SLPP, a party he ostensibly represents, is churning out to protect what little “vililajjawa” (shame) they have. For what reason?

than “a democratic leader”, that this extends even to the Rajapaksa family, and that the candidate the party fields in 2020 will have to be “at least a Pradeshiya Sabha member”. That last insinuation makes it clear that he is not happy with Gotabhaya Rajapaksa becoming the candidate. The reasons he gives are, while not vague, nevertheless complicated: he is for freedom and democracy, he is against nepotism, and he opposes racism. The racism charge fits in neatly with the UNP’s image of Gotabhaya as a Muslim bashing opportunist, an image borne more than anything else out of a photograph taken of the man and Gnanasara Thera together. The nepotism charge and harangue against the man’s democratic credentials (or lack thereof) fit in neatly with the UNP’s ‘white van’ rhetoric against his family. In other words, Welgama is subscribing to the propaganda those opposed to the SLPP, a party he ostensibly represents, is churning out to protect what little “vililajjawa” (shame) they have. For what reason?

We can speculate that it has nothing to do with the Rajapaksas or the values he claims to be standing for, and that it instead has to do with a clash between him and the other stalwarts. Since of late, he has gone public with his grievances with them, suggesting that Mahindananda Aluthgamage is a coward and that Gamini Lokuge was a member of the group that organised the burning of the Jaffna Library. We can speculate that he is probably being sidelined by the establishment in the SLPP. The conclusion, then, is that it is a case of sour grapes.

On the other hand, Welgama is no Duminda Dissanayake. He has a history. He has displayed commitment. At the end of the day, yes, commitment is a mere token in that cynical sphere called politics where anyone and indeed anything can be brought over for a song and a dance. But then again, it counts.

While Welgama’s political career is not as illustrious as Lokuge’s or Weerawansa’s, it is nevertheless long. Rajitha Senaratne, a politician one would not associate with the man, claimed once that there were essentially two kinds of people’s representatives and that Welgama belonged to the class who were “ready to spend their private assets and money for the sake of politics.” Given the accusations against him based on what he did and allegedly “picked up” during his tenure as Transport Minister, such praise seems unmerited. But as far as “history” goes, his record cannot be questioned in the way, for instance, that Lokuge’s (very validly) can.

"If rumours are true, such reservations have been harboured by other party firebrands, even the likes of Wimal Weerawansa and Gamini Lokuge. But Welgama is the first to come out publicly with his disenchantment "

His career picked up after 1989 when he contested (unsuccessfully) at the General Election, but it began seven years before, when he was given the post of organiser for the SLFP in Agalawatte by Sirimavo Bandaranaike. At the time, the SLFP was in deep waters, Basil Rajapaksa was “working” at the Mahaweli Development Project (after siding with and abandoning the Maithripala Senanayake faction), and Gamini Lokuge was getting ready to contest from the UNP in Kesbewa (he would win a year later). From Deputy Ministerial portfolios in Transport and Power and Energy under CBK, he “graduated” as Minister for Industrial Development and Ranaviru Welfare and subsequently Transport under MR the latter portfolio being considered a particularly difficult and trying one. How did he take to it? Consider that there was little to no coverage of the man’s activities from 2005 to 2010 and that there was a spike in coverage after he was appointed as Transport Minister in 2010, and you’ll realise that the man’s strengths were in that field. He had a past there. He made use of it.

During his term, the SLTB implemented measures to increase its fleet from 4,500 to 7,000, no mean feat considering it had to compete against a mafia of 18,000 private buses. The SLTB, far from becoming a profitable venture, institutionalized a culture of cost optimization. While these measures were ostensibly pro-privatization (he had to ward off accusations), they went hand-in-hand with a firmly centrist approach to the management of the SLTB fleet and property, including the Ekala workshop.

The truth is that the Welgama saga marks the first time the SLPP, which months ago seemed invincible, has ruptured from within. The state media has caught up, and it is having a field day. As a final point, then, we can ask: righteous anger, or sour grapes? Quoting Queen and “Bohemian Rhapsody”, we can answer: it doesn’t really matter.