Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

In school textbooks and in popular culture, Kasyapa I, better known as Kasyapa, continues to get a bad press. Most accounts have him as a god king, a megalomaniac consumed by greed, vengeance, and ultimately remorse. Those who have watched Lester James Peries’s film will no doubt come away thinking of him as a spoilt prince, a wayward hippie weaned away from his traditional role as a protector of the country’s sovereignty and a patron of Buddhism by a Brahmin swami played by Joe Abeywickrema.

In school textbooks and in popular culture, Kasyapa I, better known as Kasyapa, continues to get a bad press. Most accounts have him as a god king, a megalomaniac consumed by greed, vengeance, and ultimately remorse. Those who have watched Lester James Peries’s film will no doubt come away thinking of him as a spoilt prince, a wayward hippie weaned away from his traditional role as a protector of the country’s sovereignty and a patron of Buddhism by a Brahmin swami played by Joe Abeywickrema.

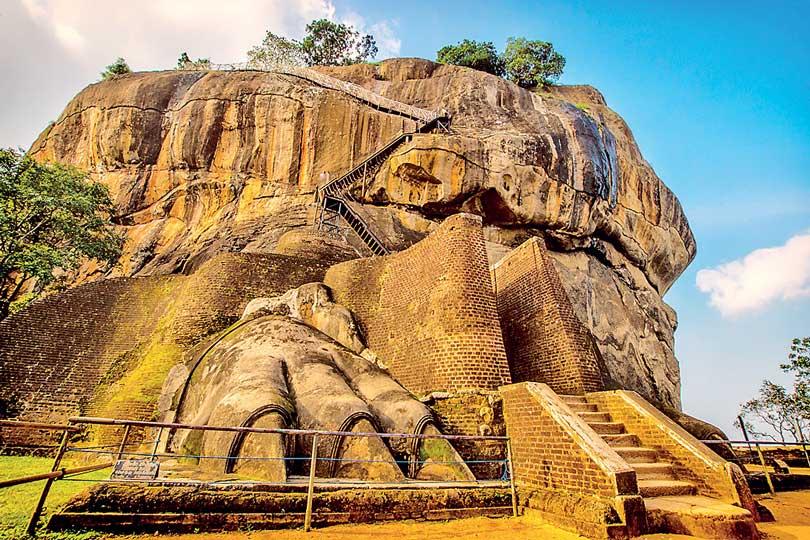

Such fanciful depictions serve to buttress the historical reality. The Pali Chronicles, including the Mahavamsa and Culavamsa, hardly have a good word for him, and as is typical of such critiques they indulge in lengthy anecdotes of his overthrow of his father and his defeat at the hands of his brother: parricide followed by a karmic payoff. Between these two events lies his sojourn at the rock fortress, Sigiriya, where he resides for 18 years and makes his base, culminating in a final encounter with the brother: a short, anticlimactic battle if ever there was one.

Given the wide availability of these accounts, it’s only natural that the story of the father, son, and brother should today conform to a particular pattern. What’s forgotten, or conveniently ignored, is the fact that the Pali chronicles, be it the original texts or their later continuations, were written from the perspective of Theravada orthodoxy and privileged one part of history over all others. This is obviously true of the monarchs or events that each of these chronicles glorifies: the introduction of Buddhism to the country by Gautama Buddha in the Dipavamsa and the unification of the Sinhala Buddhist polity by Dutugemunu in the first Mahavamsa. In the case of the Dipavamsa, with its depiction of the Sakyamuni as a ruthless evangelist-like figure striking fear into the hearts of the yakshas and evicting them from the island, what we have is an attempt by the writer to uphold the primacy of Theravada orthodoxy “by seeking authority in the past.” The situation is palpably more complex in the case of the Mahavamsa simply because it was written at a time when orthodoxy was being challenged by Mahayana heterodoxy. Unlike the Theravadins who had one monastery, the Mahavihara, for themselves, the Mahayanists had several that curried favour with, and was patronised by, the rulers of the day. The author obviously presented the latter sects in an unflattering light.

It’s only to be expected that, given all this, those who wrote these texts should be selective in not just what they wrote but who they wrote about. Wilhelm Geiger put it better than most when he noted, not a little frustratingly, that “not what is said but what is left unsaid is the besetting difficulty of Sinhalese history.” The omissions are at one level staggering: we come across only sketchy references to what could be otherwise considered as important aspects to the period these chronicles touched on and were written in.

For instance, who exactly were the yonas to whom Pandukabhaya ceded part of the land near the Western gate? Were they Greeks or were they Persians? Did they profess Buddhism or were they, as the Nestorian Cross makes it clear, Persian Christians? We have it from Cosmas Indicopleustes that by the sixth century AD there was a flourishing Christian community in the country, and although he claimed to have got information about them from traders and voyagers, including Sopatros the Alexandrian merchant, we know that when the Mahavamsa was being written the island had turned into a multi-religious trade polity accommodating not just Hindus and Jains, but also Syrian and Ethiopian Christians. This fact will prove relevant to the lingering controversy over why Sigiriya was built in the first place.

We shouldn’t be led into believing, as many critics of the Pali chronicles seem to believe, that these texts consigned an important part of local history to the dustbin. That there are passing references to “what is left unsaid” can be gleaned from the debate over Pandukabhaya ceding part of his territory to the yonas. The more plausible explanation for this, in my view, is the fact that the writers of these chronicles would have been guided by the same impulses that would have guided chroniclers elsewhere: to present the past with the present in mind, and to privilege ideological preferences over the imperatives of historicity.

What this means is that these chroniclers did not care to explain what terms like yonas meant because they had more important considerations such as privileging the Theravada orthodoxy and bringing down or denigrating the heretical sects, and also because the people of the time would have known what was meant by these terms and, therefore, explanations were simply not necessary. The authors were not thinking of their chronicles being salvaged in a thousand years from when they were written, or even 50 years; they were thinking of a present need to fulfil an objective, it being, in the case of the Mahavamsa, the need to present a religious sect in a good light over all others to regain the favour of rulers who ignored it. Appendixes did exist in the form of commentaries, yet even in them explaining certain terms would have been secondary or inimical to the achievement of the main objective; what would the primacy of Theravada orthodoxy have come to, after all, if it was proved that certain kings from that time converted not to Mahayanism but to Christianity, with one of them proclaiming himself to be the second coming of Christ and sacrificing his ministers to a great inferno?

Unlike the Theravadins who had one monastery, the Mahavihara, for themselves, the Mahayanists had several that curried favour with, and was patronised by, the rulers of the day.

One other example will suffice to shed light on the dilemma. In the Mahavamsa we are told that when Vattagamini Abhaya, defeated and distraught, flees from his palace with two of his consorts and his children, a Niganta or Jain named Giri whose temple he passes rings a bell and exclaims that “the great black Sinha(la)ya is escaping” In the Sinhala translation what we have is “Maha kalu Sinha(la)ya pala yanawa”, in Pali “Maha-kala Sihala.” The reference to one’s dark complexion was no doubt an insult reserved even for the highest monarchs, but as Senarat Paranavitana has pointed out, even the heroes of Indian literature were depicted as black; closer to home, even Kavantissa the father of Dutugemunu is referred to as Kakavan Tissa,“Kaka” ostensibly being dark. Moreover, according to Paranavitana the term “Maha-kala” means something different from “Kaka”:“Mahakala” is a synonym for Yama, the king of the Rakshas who figures so prominently under various guises in the religions of Asia and Persia. The cult of Yama, like the existence of a Christian community in the country, is as we shall see relevant to Kasyapa’s story; what we need to appreciate here is the ambivalence, the lack of elaboration, and the ellipses regarding both in these chronicles.

The writer of the Mahavamsa is acknowledged to be Mahanama Thera. We know very little of him, but many date the writing of the chronicle to after the time of the Sigiriya controversy, following the father-son-brother wars in fifth century AD Anuradhapura. While the text itself doesn’t touch on this period – it depicts events until the reign of Mahasena – it was continued 600 years later during the reign of a king under whom literature flourished and, significantly, attempts were made to rediscover the past. It is here that we ought to approach the story of Kasyapa, his father, brother, and fortress, but before that the backdrop against which the story was written and retold needs to be summed up.

Parakramabahu, I assumed the throne in 1153 AD. In most accounts of him he is said to have unified the country, firstly by putting down rebellions from regional polities and secondly by bringing the many Buddhist sects together. In other words, to unify the temporal divisions in the island, it was necessary at the same time to unify the spiritual divisions. But this does not mean that the unifier favoured one sect over another: a R. A. L. H. Gunawardena has pointed out, what happened in reality was that Parakramabahu I, to keep at bay the factional struggles in the Buddhist order, patronised them all and reached a compromise. Theravada orthodoxy would not regain the primacy it once enjoyed for at least another 600 years, when the Sangha as a whole had deteriorated and, by the time of Sri Vijaya Rajasinghe the first Nayakkar king, barely two higher ordained monks could be found from the entire country to continue the line of succession. At the time of the writing of Mahavamsa II,Mahayanism thus flourished, and scholars from abroad who followed it found a welcome home in the royal court. One of them was a monk from Palembang, Indonesia; by name Buddhamitra, he is the main extant source we have for the story of Sigiriya, which we shall get to next week.

To be continued...