Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

I stayed awake for hours—my whole being lifted up in earnest prayer for Lalith, asking God to heal him

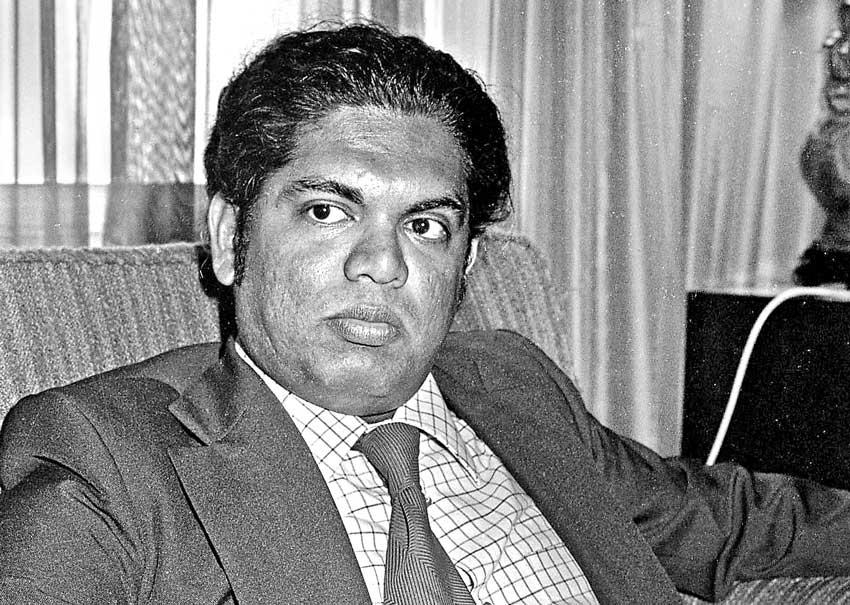

Lalith Athulathmudali

The article “Recalling that narrow escape” of the parliament terrorist grenade attack in 1987, published in the Sunday Times on August 15, 2021, prompted me to write my own personal recollection of details of that fateful day.

The article “Recalling that narrow escape” of the parliament terrorist grenade attack in 1987, published in the Sunday Times on August 15, 2021, prompted me to write my own personal recollection of details of that fateful day.

The 18th of August 1987 began like any other Tuesday, when I provided anaesthesia for a busy surgical list for Dr Yoheswaran in Theatre-5 of the Sri Jayawardenepura General Hospital (SJGH). Just after our second case an announcement was made on the PA system, “Dr Yoheswaran, please come to the ETU (Emergency Treatment Unit) immediately.” We thought perhaps a VIP patient had come to see him. The announcement was repeated. Yoga asked, “Should I change out of my theatre clothes?” Dr Kenneth Perera who was there said, “Just go as you are and see what they want.”

|

Surgery in progress with Dr Yoheswaran in the foreground |

Minutes after Yoga had left, I got an irresistible urge to run down to the ETU. Call this compulsive feeling ‘extra sensory perception’, ‘thought Transference’, or what you like. Being a Christian I believe it was ‘divine direction’. I ran out in my theatre scrubs and shoes. I ran down the stairs; pushing people out of my way. I had a hazy impression of surprised faces as I rushed through the swing doors of the ETU.

I halted near a trolley surrounded by several people frozen in apparent shock. I saw a well-built figure in blood spattered white clothes, lying semi-prone on the left lateral side, with his right arm hanging over the side of the trolley. I instinctively reached for the hand and groped for the radial pulse—it was imperceptible. When I looked down at the figure lying so still, taking an occasional gasping breath, and a glazed look in his eyes, to my shock I recognised it was Lalith Athulathmudali. My first thought was this was my husband Mahendra Amarasekera’s beloved ‘Sir’ (Lalith had been his lecturer in Jurisprudence in Law College, and they had moved closely ever since).

I grabbed a cannula being held by an ETU doctor and inserted it into a vein at the back of the right hand. The circulation was so poor there was no ‘flush back’ to indicate I was in the vein. But I knew I was in—I couldn’t afford to miss! I connected a normal saline drip to the cannula and opened it fully. I realized this was not good enough and asked for a ‘Haemacel’—a blood substitute, and started squeezing the plastic bottle so the fluid was literally pouring into the vein. When half the bottle was transfused, I could feel the pulse return. I looked up at Dr Rangith Attapattu who was standing there and said “It’s alright now sir.”

Yoga did a quick assessment of the injuries. There were shrapnel wounds on both legs, the back of the chest and buttocks, and an alarming entry wound just below the left nipple; later confirmed as not being a penetrating chest injury. It was also a relief to see clear urine on catheterization, indicating the kidneys were functioning.

Suddenly Lalith opened his eyes and asked me, “What is my pressure? Is it low?” I replied by saying, “It’s a little low sir, but not bad.” Then he said, “I normally have low pressure. Ask my GP, she will tell you.” When I asked him if he could remember the actual value he said “about 60”. I told him he must be thinking of his pulse rate and not blood pressure. I asked him if he knows his blood group and he replied, “The common one.” A Blood Bank doctor rushed up with a bag of blood. I asked if it had been cross matched and when she said “no” I said, “Please do an emergency cross match and bring it, I don’t want to take the risk of giving uncross-matched blood. I can hold his pressure till then.”

Yoga was puzzled by the initial state of collapse. He concluded it was ‘neurogenic shock’ as there was no evidence of any internal bleeding at this stage. Kenneth administered morphine intravenously. We began wheeling the trolley out of the ETU. Lalith asked, “Where are you taking me taking me?” I replied, “First to the X-Ray department and then to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).” Once the minister was lifted on to the X-Ray table everybody left the room before the films were taken. I remained as I did not want to leave him alone with his condition being far from stable. I said, “I don’t think you can remember me sir, I’m…” Before I could complete the sentence he smiled and said, “I know, you are Mahendra’s wife.” I was surprised as I had only met him twice before; the last occasion being two years prior, at Mahendra’s induction as President of the Rotary Club of Mt Lavinia, when the minister was the Chief Guest.

He was rather concerned about an injury to his left thumb, so I got an X-Ray of his left hand taken as well. Later I learned Lalith was left-handed. One pint of blood had been cross matched by now and brought to the X-Ray room and I transfusion commenced.

We took him to the ICU and Yoga started cleaning and dressing the wounds. Lalith said his chest was hurting and I assured him there was no injury to his heart. He then said, “I feel rather sleepy – can I close my eyes?” I told him he had been given morphine and that’s why he was feeling sleepy. I said, “Go ahead and sleep – we will look after you.” No grumble or moan escaped his lips, though he must have been in pain.

We got the X-Ray films and noticed several shrapnel had penetrated the abdomen. There was one that was near the 1st Lumbar vertebra; dangerously close to the Aorta. The blood pressure that had been steady between 90–100mm Hg started dropping. Yoga examined Lalith’s abdomen repeatedly. At first the minister said he had no pain, only discomfort. A little later he admitted he felt pain. Yoga was able to elicit ‘rebound tenderness’ which is evidence of peritoneal irritation. The blood pressure had fallen to 80mm Hg by now. Yoga asked fellow surgeon Dr Premaratne for his opinion. He agreed with Yoga’s findings. In spite of differing opinions, Yoga made the correct decision to proceed with a laparotomy. He explained it to Lalith who showed no fear at all. He asked, “You have to open me? Go ahead.” Then he asked, “Will you do it under local or general anaesthesia?” I explained we had to give him a general anaesthetic as it was better for him to be asleep during the operation.

Suddenly his wife Srimani was there. She stayed quietly by Lalith’s side, not getting in the way and being outwardly calm. We took Lalith to the Operating Theatre and connected him to the monitors and started inducing anaesthesia. Kenneth injected ‘Pentothal’ through one of the cannula while I held an oxygen mask over Lalith’s face. Lalith slowly drifted off to sleep. I secured his airway and connected him to the anaesthetic ventilator.

Yoga began the surgery and when he opened the abdomen there was a total 4000ml of blood in the peritoneal cavity. Yoga and Premaratne first removed the ruptured spleen that was bleeding briskly. Then they looked carefully for less obvious, but equally life threatening injuries. There were several perforations of the bowel which were meticulously sutured by Yoga. He found a haematoma near the pancreas, which after much deliberation, he decided to leave alone. Finally the difficult, but correct decision was to perform a ‘temporary de-functioning colostomy’. The whole procedure took 4 ½ hours, and we had to transfuse 11 pints of blood. Despite we having a few anxious moments Lalith’s condition remained remarkably steady throughout the procedure. Once the surgery was over we took him back to the ICU.

Effects of the massive transfusion

It was about 4.00pm. One by one the others left, but I did not. I know only too well the problems that could follow major surgery and massive transfusion. I took a blood sample and sent it to the lab to check the clotting profile. My fears were justified seeing the reports. The Haematologist and I got down ‘Fresh Frozen Plasma’ and ‘Platelet Concentrate’ urgently from the Colombo Central Blood Bank to counteract the effects of the massive transfusion.

I was still standing by the bed with Srimani when Lalith opened his eyes and asked, “Was it worth it?” and I replied with a heartfelt, “Yes sir”– had we not opened him up, or even delayed the operation, the result would have been disastrous. Then he asked, “How are the other injured? Am I the worst injured?” I saw Lalith’s Chief of Security Muthubanda making frantic negative signals, conveying to us not to say anything about Keerthi Abeywickrama who was killed in the blast. Srimani said, “The others are alright. Percy Samaraweera is also here. He also had an operation.” I was touched by Lalith’s concern for others in spite of being mortally wounded himself. He drifted back to sleep.

I arranged for a hospital vehicle to bring Yoga back for a night round, and left specific instructions with the SHO Anaesthesia on duty to call me at the slightest change in Laliths’s condition, and went home. It was pitch dark and raining. I was rather nervous driving alone and was relieved when Srimani instructed Lalith’s security to escort me.

At home I was mentally, physically, and emotionally exhausted. I had no appetite, though I had not eaten anything the whole day. I tried to sleep, but sleep evaded me. I stayed awake for hours—my whole being lifted up in earnest prayer for Lalith, asking God to heal him. We had done all that was humanly possible. But healing comes from God. And thank God that my prayers and that of many thousands of others were answered, that fateful day.

(The writer is a Retired Senior Consultant Anaesthetist at SJGH and Past President of the Sri Lanka Medical Association and the College of Anaesthesiologists)