Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A deminer using a metal detector with precision and care

PIX BY KITHSIRI DE MEL

A land infested with landmines prior to demining operations undertaken by HALO Trust

|

As of 31 December 2023, there were 654 areas primarily located in the North and East, as well as other subordinate districts, known to contain anti-personnel mines In December 2017, Sri Lanka acceded to the Convention on the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines According to Article V of this Convention Sri Lanka needs to declare itself as a mine-free country by 2028 The Sri Lanka Mine Action Completion Strategy developed by the National Mine Action Centre was endorsed by the Sri Lankan government in March 2023 |

Hours before the break of dawn on a humid Tuesday, this writer along with several other individuals sat at a 20-minute debriefing inside a temporary shelter setup a few meters away from the Mankulam junction in the North of Sri Lanka. With mobile phones aside and personal protective clothing intact, we were getting ready to follow our guide a few kilometers into the jungle. We would have loved to believe that it was just another regular jungle trek. But, it was not. Instead, this writer along with a team of experienced ex-soldiers were on their way to get a first-hand experience of de-mining operations taking place inside a thick jungle patch in Mankulam, now declared as a Confirmed Hazardous Area (CHA) – at the exact location where the Jayasikuru operation took place.

Hours before the break of dawn on a humid Tuesday, this writer along with several other individuals sat at a 20-minute debriefing inside a temporary shelter setup a few meters away from the Mankulam junction in the North of Sri Lanka. With mobile phones aside and personal protective clothing intact, we were getting ready to follow our guide a few kilometers into the jungle. We would have loved to believe that it was just another regular jungle trek. But, it was not. Instead, this writer along with a team of experienced ex-soldiers were on their way to get a first-hand experience of de-mining operations taking place inside a thick jungle patch in Mankulam, now declared as a Confirmed Hazardous Area (CHA) – at the exact location where the Jayasikuru operation took place.

National targets

Land mines and Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) including unexplored bombshell, artillery shells and missiles, mortar bombs, anti-tank projectiles are gruesome legacies of a protracted war. In December 2017, Sri Lanka acceded to the Convention on the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction, known informally as the Anti-Personal Mine Ban Convention.

According to Article V of this Convention Sri Lanka needs to declare itself as a mine-free country by 2028. But those working at the ground level opine that this would be a tough challenge given the prevailing circumstances. Currently there are five de-mining operators engaged in mine clearance activities in the North of Sri Lanka. Amongst them, the Sri Lanka Army Humanitarian De-mining Unit, Delvon Assistance for Social Harmony (DASH) and Skavita Humanitarian Assistance and Relief Project (SHARP) are national Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) while The HALO Trust and Mines Advisory Group (MAG) are international NGOs. As of 31 December 2023, there were 654 areas primarily located in the North and East, as well as other subordinate districts, known to contain anti-personnel mines, totaling 16,831,534 square meters. Additionally, there were 171 areas suspected to contain anti-personnel mines, totaling 4,743,729 square meters. These areas, whether confirmed or suspected to contain anti-personnel mines, are distributed across 11 districts including Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mannar, Mullaitivu, Vavuniya, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Puttalam, Ampara, Batticaloa and Trincomalee. The Sri Lanka Mine Action Completion Strategy developed by the National Mine Action Centre (NMAC) was endorsed by the Sri Lankan government in March 2023. One of its main strategic objectives is to release lands for resettlement programmes and implement an inclusive and transparent completion survey to allow Sri Lanka to complete its targets according to Article V. As of 21 May 2024, the completion survey has been commenced throughout 425 GN divisions, of which 313 have been validated. Out  of these 313, survey teams concluded that there is no further evidence and/or suspicion of other explosive ordnance (EO) contamination in 201 GNs and recommended them for declaration.

of these 313, survey teams concluded that there is no further evidence and/or suspicion of other explosive ordnance (EO) contamination in 201 GNs and recommended them for declaration.

Significant challenges

In September 2023, seven-year old Sudarshan had walked towards the forest patch which we visited in Mankulam to collect firewood with his grandfather. While inside the jungle he had discovered an unidentified object and had asked what it was from his grandfather. The senior had immediately requested his grandson to throw the object away. A minor explosion had followed, injuring the two individuals. It was later revealed that the child had picked up a 40mm grenade launcher round.

Following the incident, the DASH de-mining operation team deployed its staff to investigate the area.

The survey revealed evidence of explosive ordnance including land mines located in close proximity to human settlements within a 100-metre radius. One significant challenge faced by de-mining operators is with regards to cases of previously unknown contamination which then increases the contamination baseline by several kilometres. At the time the 2028 deadline was given around 17.2 square kilometres had been contaminated. But once the process was increased and enhanced and the surveys were expanded officials believe that a remaining area of 25 square kilometres or more are yet to be cleared. In addition the current capacity and resources aren’t sufficient to complete the process by the expected deadline.

According to DASH officials, this area was heavily mined as both the Sri Lanka Army and the LTTE were trying to capture this land as it was a critical communication hub. Since September 2023, de-mining operations are still underway at this location.

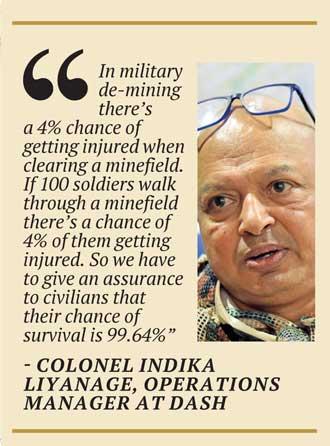

The prevailing challenge faced by officials is to locate land mines laid by the LTTE. The mines laid by the terrorists are not recorded and therefore we don’t know the exact locations. Whenever the Army created a Line of Defence, the LTTE would create a bund within a one kilometer distance. So, the only option is to find out their Lines of Defence, says Colonel Indika Liyanage, Operations Manager at DASH.

Mine clearance cannot be done with time constraints. This was evident when we observed how de-miners were carefully raking through the soil without causing any disturbance to any  potential explosive device lying several centimeters beneath them. “In military de-mining there’s a 4% chance of getting injured when clearing a minefield. If 100 soldiers walk through a minefield there’s a chance of 4% of them getting injured. So we have to give an assurance to civilians that their chance of survival is 99.64%. After the field has been cleared we have to play a football match or some kind of activity to reassure them that it is a safe area to live in,” he added.

potential explosive device lying several centimeters beneath them. “In military de-mining there’s a 4% chance of getting injured when clearing a minefield. If 100 soldiers walk through a minefield there’s a chance of 4% of them getting injured. So we have to give an assurance to civilians that their chance of survival is 99.64%. After the field has been cleared we have to play a football match or some kind of activity to reassure them that it is a safe area to live in,” he added.

Other challenges include civilian interferences where people would continue to walk into forest patches to fetch firewood, fell trees to make furniture, sand mining, poaching and other legal and illegal activities. “The most dangerous kind of interference is with regards to explosive harvesting. Civilians would remove mines, extract the explosives and sell to others for fishing and other purposes. In 2018, two civilians were killed while trying to hunt for mines in Muhamalai,” Col. Liyanage further said.

DASH receives funding from five countries including Japan, USA, Australia, Germany and Switzerland. However, various challenges persist with regards to funding but the officials are determined to work towards the national objectives of declaring Sri Lanka mine free country in four years’ time.

A dangerous job

Mines are known to be the most deadly weapon that man made against mankind and it doesn’t matter who laid it as anybody could become a victim of a land mine explosion. But mine clearance activities have been a potential source of income for the extremely needy community in these parts of the country. People live in abject poverty and face various social issues as a result. Many women are widowed as their spouses have abandoned their families, youth unemployment is at an all-time high and therefore, mine clearance opportunities have been a ray of hope for many individuals.

In almost all de-mining operations, a majority of de-miners are women. At DASH, out of around 360 personnel, around 22.5% are females.

In terms of training there’s a basic de-miner course to be followed. Col. Liyanage explained that the National Mine Action standards are derived from International Mine Action standards which are country specific. “According to the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) the type of training, selection criteria and all other standards and guidelines are being included. The accreditation procedure determines the course of action for a particular De-mining agency. It is only after this certificate is issued that we can start work. As the field manager I should have the Level III qualification for Explosives Ordnance  Disposal. De-mining agencies currently carry out recovery of explosives and the disposal is being done by the Army. We have two trained paramedics on site. A multi-casualty vehicle and two trained medics have been deployed to each one of our sites to respond to any emergencies. We have 12 teams and there need to be 24 trained paramedics.

Disposal. De-mining agencies currently carry out recovery of explosives and the disposal is being done by the Army. We have two trained paramedics on site. A multi-casualty vehicle and two trained medics have been deployed to each one of our sites to respond to any emergencies. We have 12 teams and there need to be 24 trained paramedics.

Without an ambulance and medic we cannot start work on that day. The vehicle should be ready at all times and the driver needs to check if everything is in place every two hours. By 2018 five de-miners had suffered injuries. Two others were killed during a UXO explosion. Thereafter we increased supervision at this site. Another girl got injured but apart from accurate SOPs there could be defaults in these mines. The conditions of these mines have changed. In these areas, plastics decay due to salinity levels in water. Once the plastics decay the internal mechanism gets exposed,” he added.

People work under heavy stress levels. Therefore they are being advised to work according to the SOPs. “The medics should observe their behaviors. De-miners are not allowed to intoxicate themselves if they have to go to the field the next day. They have to be conscious about their surroundings. Apart from mines there are grenades attached to tripwires and other kinds of traps inside the jungles. The tripwire is not visible to the eye. If they are not conscious about their surroundings, either that individual or someone else would be vulnerable to an injury or even be killed.

Therefore, the medics monitor their behavior all the time,” Col. Liyanage explained further.

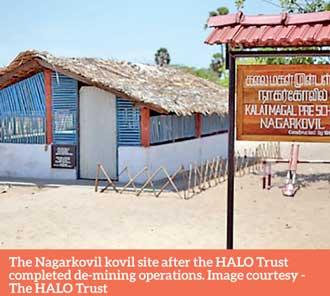

Mine clearance activities by The HALO Trust

HALO has been operating in Sri Lanka for 22 years, starting operations in Jaffna in 2002. This Organisation has remained operational throughout the conflict, pioneering post-war clearance efforts in Kilinochchi and Mullaitivu Districts after the end of hostilities in 2009. Since then, HALO’s clearance activities have predominantly concentrated on the districts of Jaffna, Kilinochchi and Mullaitivu.

To date, HALO has released over 118 square kilometres of land, safely clearing over 1.2 million items of explosive ordnance, including 291,000 anti-personnel mines. HALO currently employs 1,090 staff with a 62:38 (Male : Female) gender balance while 45% of its operations staff (de-miners) are women. HALO represents approximately 41% of the country’s total mine action capacity.

As of 2024, HALO clears an average of approximately 1,000 anti-personnel mines a month. Over 280,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) have returned to HALO cleared land. The HALO Trust currently utilises both manual and mechanical methods to detect and excavate mines. One of its major mine clearance operations at the Muhamalai Lagoon is believed to be a first of its kind and its officials are determined to assist Sri Lanka in declaring itself as a mine free country by 2028.

The HALO Trust also offers an employee transition project providing psychosocial support to its personnel, training them with literacy skills, women empowerment and other activities to allow them to find smoothly transition into another job once Sri Lanka becomes mine free.

The life of a de-miner

While at the minefield visitors are required to follow various markers indicating whether they are at a high risk zone or not. We were instructed to walk along a particular that has been declared as mine free in order to avoid any accidents. De-miners were engaged in their respective tasks at various isolated areas, paying attention to every minute sound that would be emitted from the devices buried beneath the ground.

For de-miners, their day starts as early as 3.00am, where they would prepare their meals and get ready to hop aboard the transport service provided by respective de-mining organisations. They arrive at the minefield at the break of dawn, wear their personal protective clothing and get to work. They get two breaks, a tea break and breakfast and 10 minute breaks in between. Given the fact that it is challenging to work in extreme heat conditions they finish work by 1.00pm. However, their life is extremely uncertain as they deal with explosive devices that have been buried deep in the ground for many years. In case of an injury they have to follow a coordinated casualty evacuation procedure which would minimize threats to fellow de-miners.

During their break, the Daily Mirror spoke to several de-miners employed by DASH.

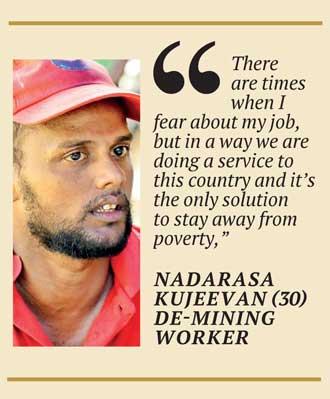

Nadarasa Kujeevan (30) from Ellakadu was desperately looking for employment when a friend recommended that he join mine clearance activities conducted by DASH. “Initially I earned a daily income of about Rs. 850 and it was difficult to raise my family. I had gone to Jaffna when I heard about an ongoing recruitment opportunity at DASH. I remember taking a bus from Jaffna and remained in the queue to obtain a token. There were many tall and healthy-looking individuals around me and my hopes faded when the person in front and behind me received tokens and were asked to report to work in two days. I immediately met with the field manager and told him about my situation. He understood what I was experiencing and following a medical checkup I was selected. I felt happy because I knew that I had a job to feed my family,” said Kujeevan.

When asked about the nature of his job he said he will never forget how two of his colleagues sustained injuries during a mine explosion that happened sometime back. “There are times when I fear about my job, but in a way we are doing a service to this country and it’s the only solution to stay away from poverty,” Kujeevan said.

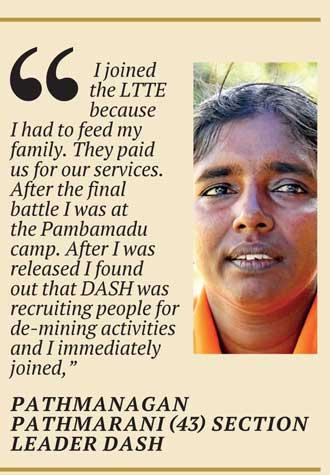

De-mining is a profession that encourages gender diversity and the social stigma is slowly fading away. Pathmanagan Pathmarani (43) from Akkarayan arrives at the minefield by about 5am. As a former LTTE member employed at the LTTE’s traffic police, Pathmarani reflected on her life prior to becoming a de-miner. “I come from a family of eight. I joined the LTTE because I had to feed my family. They paid us for our services and that way I was able to look after my family. After the final battle I was at the Pambamadu camp for two years. After I was released I found out that DASH was recruiting people for de-mining activities and I immediately joined. This was in 2010 and I have been working here for 14 years,” said Pathmarani.

She is now a section leader at DASH and she feels that she’s duty bound to ensure that the lands are free of explosives. “I feel that the war was a waste of time and resources. Now everybody is living in peace and harmony. There were days when I felt that this is a difficult job for a female but now we all feel equal,” she said.

Members of the staff are aware of the risk ahead of them. They have been trained and re-trained and they work according to SOPs to minimize risk on their lives. One wrong move will seal their fate. They endure the physical and psychological pain and brave all challenges to overcome poverty. De-mining is considered as one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Many people engaged in de-mining operations have experienced a brutal past. They were thrown towards poverty and have been forced to engage in a deadly profession as their primary mode of survival. Once de-mining operations are completed, they need to be reintegrated into other sectors. As one of its strategic objectives, the NMAC is currently working on staff transition programmes in terms of capacity building activities for men and women so that they could gain new skills and find alternative employment after redundancy. The overall goal is to preserve and strengthen safe and sustainable livelihoods of thousands of women and men in Sri Lanka’s northern and eastern districts.

As the sun slowly positioned itself directly above us, it was a sign for the de-miners to get back to work before the humid atmosphere made it unbearable for anybody to stay outdoors.

(This story was produced with the support of InterNews)