Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

At present the Hambantota saltern lacks surplus reserves, but till a year ago it had the ability to supply salt year-round without running into a shortage

To meet the current demand, substandard salt, containing impurities like dust and shells, is being released into the market

To meet the current demand, substandard salt, containing impurities like dust and shells, is being released into the market

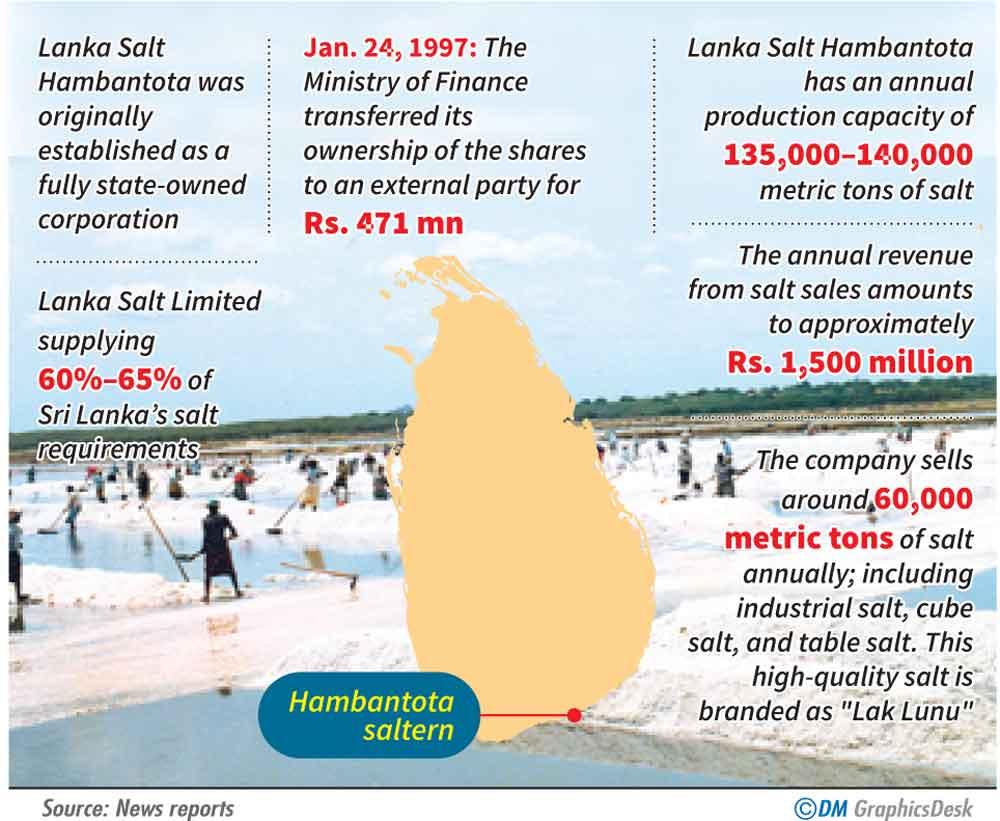

Lanka Salt Hambantota was originally established as a fully state-owned corporation. On January 24, 1997, the Ministry of Finance transferred its ownership of the shares to an external party for Rs. 471 million. At the time of this transfer, approximately 90% of the shares was held by the Employees’ Trust Fund Board, and 10% of those shares was subsequently allocated to the employees of the saltern. Since then, the saltern has been registered under the Companies Act No. 07 of 2007, and functions as a company.. Lanka Salt Hambantota has an annual production capacity of 135,000–140,000 metric tons of salt. Alongside Hambantota Maha Lewaya, the Koholankala and Palatupana salterns have also been established. The annual revenue from salt sales amounts to approximately Rs. 1,500 million, with Lanka Salt Limited supplying 60%–65% of Sri Lanka’s salt requirements. The company sells around 60,000 metric tons of salt annually; including industrial salt, cube salt, and table salt. This high-quality salt is branded as “Lak Lunu.”

Lanka Salt Hambantota was originally established as a fully state-owned corporation. On January 24, 1997, the Ministry of Finance transferred its ownership of the shares to an external party for Rs. 471 million. At the time of this transfer, approximately 90% of the shares was held by the Employees’ Trust Fund Board, and 10% of those shares was subsequently allocated to the employees of the saltern. Since then, the saltern has been registered under the Companies Act No. 07 of 2007, and functions as a company.. Lanka Salt Hambantota has an annual production capacity of 135,000–140,000 metric tons of salt. Alongside Hambantota Maha Lewaya, the Koholankala and Palatupana salterns have also been established. The annual revenue from salt sales amounts to approximately Rs. 1,500 million, with Lanka Salt Limited supplying 60%–65% of Sri Lanka’s salt requirements. The company sells around 60,000 metric tons of salt annually; including industrial salt, cube salt, and table salt. This high-quality salt is branded as “Lak Lunu.”

Audits of the company are conducted under the supervision of the Auditor General, with its progress reported to the Parliamentary COPE (Committee on Public Enterprises). It is classified as a government-owned enterprise

“Lak Lunu” became popular among consumers in Sri Lanka for its exceptional cleanliness and quality. However, the current production standards of Lak Lunu are not satisfactory at all. Dust, shells, and other impurities are now mixed with the salt at the Hambantota saltern and its affiliated salterns. The salt is being released to the market sans a proper inspection, leading to the withdrawal of its ISO 20,000 certification due to substandard quality.

No salt production in 2023

The lack of purity in the salt produced has also been a cause for the saltern to lose its ISO certification. While some attribute the decrease in salt production to recent floods, an on-site visit to Hambantota revealed that none of the salt pans were actually flooded. The real reason for the salt shortage in the country appears to be the absence of salt production at the salt pans in 2023. Typically, salt production occurs during the Yala and Maha seasons; which is around March–April and October–November, respectively. Once the production process begins, it naturally continues to produce the salt the country needs. Any surplus in production is stored for future use.

The authorities of the Hambantota Saltern have attributed the lack of salt production to flooding, but this claim appears questionable. Even during the tsunami disaster, when the Hambantota Saltern was closed for about six months, the country didn’t face a need to import salt due to a surplus in storage.

This newspaper made attempts to determine the reason behind the need to import salt due to flooding. It was reported that salt production at the Hambantota saltern had ceased in 2023. The primary reason for this stoppage appears to be the saltern being ranked fourth among loss-making enterprises. As a result, the previous government planned to sell the Hambantota saltern, which led to the suspension of production last year. The Lak Lunu branded salt that entered the market reportedly came from existing stocks.

In recent times, key production processes—such as pumping seawater into salt pans, allowing salt to crystallise, and employing workers to harvest the salt—have not taken place. Additionally, large quantities of salt stocks were released to the private sector just weeks before the presidential election; allegedly to create an artificial shortage of salt. Employees at the Hambantota salt factory confirmed that this was intentional and warned that insufficient salt production could lead to a future shortage. To meet the current demand, substandard salt, containing impurities like dust and shells, is being released into the market, according to these employees.

When conducted properly, the Hambantota saltern has the capacity to produce around 100,000–110,000 metric tons of salt annually. However, this year’s harvest has been significantly impacted by changes in climate, yielding only 40,571 metric tons across both seasons. This substantial decline has further contributed to the shortage of salt. While increased production might be possible during the dry season, the rainy season limits the potential for higher yields.

Currently, the Hambantota saltern lacks surplus reserves, but back then it had the ability to supply salt year-round without running into a shortage. Factory employees attribute this year’s shortage primarily to climate change.

Salt from the salterns at Hambantota, Bundala and Palatupana is released to the market in batches, and therefore has ISO certifications for quality, including ISO 9001 and ISO 20000 for LakLunu. However, the ISO 20000 certification is no longer printed on salt packets. This is reportedly due to the salt being contaminated, containing impurities like dust and shells and such salt being released to the market. Investigations revealed that the removal of the ISO 20000 certification from the salt packets was done at the request of the Sri Lanka Standards Institute.

Salt is classified into four grades: Grade 1 and Grade 2 and are suitable for food consumption, while Grade 3 and Grade 4 are designated for industrial use. Currently, the Hambantota Salt Factory lacks sufficient stocks of Grade 1 and Grade 2 salt for consumption. Only a small quantity of Grade 1 salt remains, which is inadequate to meet the demand. The current stock primarily consists of Grade 3-4 industrial salt. It was revealed that Grade 3-4 industrial salt is being washed, powdered, and sold in the market as table salt.

Political interference

However, this process has compromised the quality of Lak Lunu salt in the market. When the industrial salt is crushed, shells become mixed with the product. Employees at the Hambantota saltern have raised concerns about the health risks of consuming salt mixed with shells. According to the employees, the clean salt that is released contains dust, impurities and shells. Many of these salt packets, containing such impurities, have already been returned to the factory.

The employees have called on the Sri Lanka Standards Institution and the Consumer Affairs Authority to investigate the issue and implement a solution. It has been decided to import salt. This decision follows the recent cabinet approval to import 35,000 metric tons of salt from India to prevent a shortage in the country. The hasty sale of salt stocks held by the saltern to the private sector has also significantly contributed to the current salt shortage.

The employees of the Hambantota salt factory largely attribute the current salt shortage to political interference. Grade 1 and Grade 2 salt, obtained from Palatupana saltern was sold to the private sector even when it was evident that a salt shortage was imminent. Additionally, there was no salt production last year, at least in one season, and this year’s production decreased significantly due to rain. The sale of salt during these circumstances has exacerbated the shortage, necessitating salt imports.

The Hambantota saltern should be capable of continuously supplying the country with the required amount of salt. However, it has now been decided to import salt. Domestic salt production may take approximately six months to recover and alleviate the current shortage. This shortage could persist until April or May this year (2025). Furthermore, even if salt production resumes during this period, potential disruptions such as rain or other disasters could further delay recovery. This would necessitate importing salt from India once again to address the shortage. While plans are currently underway to import salt from India, several practical challenges have emerged that are hindering the importation of salt stocks.

There is the potential for adopting new technologies in salt production. Such advancements could increase yields and quality. However, according to its employees, inefficiencies of the previous management of the Hambantota saltern hindered the implementation of these technologies. Salt produced with water from the Kolangala area often contains shellfish as an impurity. Proposals to mitigate this issue were disregarded by previous administrations, raising concerns about the future of Sri Lanka’s salt production industry.

During the tenure of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, salt imports to Sri Lanka were entirely halted, and the Hambantota Saltern became the primary supplier for private companies and industries. This approach initially allowed the saltern to meet production targets. However, due to current challenges, salt production has significantly decreased, leading to an unavoidable salt shortage in the country. While importing salt from India may alleviate the crisis to some degree, it is uncertain if it will fully meet the nation’s needs.

Usually, salt harvesting is not feasible during January and February. The current crisis could be mitigated if the expected salt harvest is achieved by the end of March. If not, the country might face a severe shortage.

The main cause of the salt shortage is attributed to administrative weaknesses at the Hambantota saltern, according to its employees. Mismanagement has hindered the once efficient operation of producing salt. For example, water pumps often fail to function when seawater needs to be pumped into pans at the right time. Delays in pumping water subsequently postpone the salt production process; increasing the likelihood of rain disrupting the harvest. Such inefficiencies have impaired salt production.

Previously, due to administrative weaknesses and issues with the company responsible for iodine procurement, another type of flour was mixed into salt as a substitute for iodine during production. This salt was even released to the market. However, the iodine issue has now been resolved, and salt is currently being produced and contains iodine, according to the employees. The Hambantota saltern currently lacks a permanent chairman with the operation operating only under a CEO. Workers at the factory urged the government to appoint a capable chairman promptly to address the administrative challenges contributing to the salt crisis.

The authorities of the Hambantota Saltern have attributed the lack of salt production to flooding, but this claim appears questionable

(Photographs by Waruna Wanniarachchi)

The main cause of the salt shortage is attributed to administrative weaknesses at the Hambantota saltern, according to its employees

When this newspaper inquired about the situation, the Assistant General Manager of Lanka Salt Hambantota R.M. Gunarathna, stated that plans are in place to import 30,000 metric tons of salt to meet the country’s needs for salt. This import will be carried out jointly by Lanka Salt Hambantota and the private sector. When questioned about the presence of shells and waste in salt packets and the potential shortage, he suggested contacting the Trade Manager, Sumal Madhusanka, and the CEO, Ajith Sammuganathan, to obtain further details.

Trade Manager Sumal Madhusanka denied the claims of salt containing shells and waste, asserting that no such contaminated salt had been returned to the factory.

Efforts were made to contact Ajith Sammuganathan, CEO of the Hambantota Salt Factory, to seek clarification on these matters, but there was no response to our calls. Similarly, attempts made to reach the Sri Lanka Standards Institute to confirm whether the ISO 20,000 quality certificate had been discontinued also yielded no response.