Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

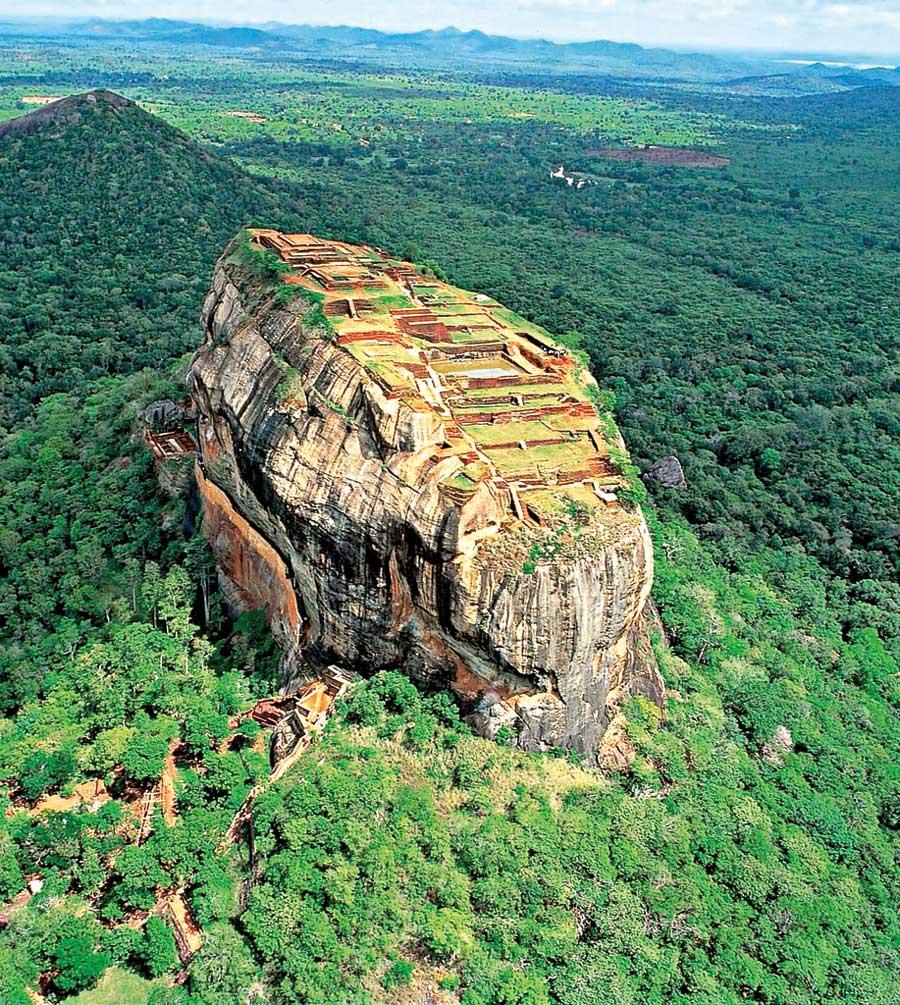

"With the prime place in Sigiriya given to the lion, Mahavamsa states: Kasyapa, in fear of his brother, fled to the great rock Sigiriya. He cleared the land roundabout, surrounded it with a wall and built a staircase in the form of a lion"

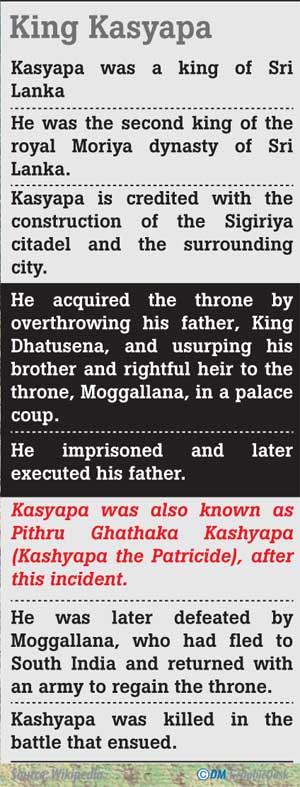

Mysteries of Sigiriya, continue to inspire scholars to unravel its hidden stories. Examining the psychology of its architect and presenting a startling interpretation of his edifice is anthropologist Professor Gananath Obeyesekere in his “The Buddha in Sri Lanka, Histories and Stories.”

edifice is anthropologist Professor Gananath Obeyesekere in his “The Buddha in Sri Lanka, Histories and Stories.”

Expounding his theory under the chapter “Sigiriya narratives: tellers of stories, writers of histories,” he writes: the significance of Sigiriya is in relation to the psychology of the father-killer in which he (Kasyapa) commemorates the arche-typal father-killer of Sinhala myth Sinhabahu (lion limb) who after killing his father, the lion, constructed a new city named “Sinhapura” – the lion city.

“Kasyapa, by identifying with this primordial parricide in Sinhala history and the conscienceless killer of his father the lion, like his ancestor, lacked a conscience or a sense of remorse. The conspicuous nature of this creation is evident in what the Mahavamsa says as well as our current knowledge of the archaeology of Sigiriya that the formal entrance to Sigiriya is through the limb of the lion.

"Kasyapa has built what he considered to be another Sinhapura, the city of the lion which of course is what Sigiriya also means"

“Kasyapa has built what he considered to be another Sinhapura, the city of the lion which of course is what Sigiriya also means.”

It seems to the author that Kasyapa had adopted a model from the past, what he calls a “myth model” and recreated it in his magnificent creation.

With the prime place in Sigiriya given to the lion, Mahavamsa states: Kasyapa, in fear of his brother, fled to the great rock Sigiriya. He cleared the land roundabout, surrounded it with a wall and built a staircase in the form of a lion (MV. 38:3-4.) Hence the name of the rock : Sigiriya, Sinhagiri, Sihagiri meaning the lion rock (perhaps having the extended meaning of the “Lion City”.)

“Moreover, the present lion is represented in his limbs and it is through the lion limb that one ascends the mountain nowadays; and of course Sinhabahu means “lion-limb.” It is extremely unlikely that a full scale lion constituted the entrance of Sigiriya, given the formidable dimensions of the lion-limb. Sinhala sculptors could have conceived a full lion on the basis of the extant lion-limb but they could not have implemented such a figure whereas “lion-limb” architecturally was feasible.”

" Kasyapa’s life of hedonism was a way of overcoming the guilt of parricide or rather not permitting guilt to surface by embracing the pleasure principle and living like a divine king enjoying the life of senses"

Was Sigiriya built within eighteen years? The author disputes this time period given by Mahavamsa calling it “fiction” by depicting the affinity between the oral and the written, between history-writing and story-telling. Obeyesekere who notices a strong preoccupation of the Mahavamsa author with the number eighteen, dismisses that Kasyapa built Sigiriya in the first part of his reign of eighteen years. He says it is not unlikely that Kasyapa reigned for much longer.

Obeysekere, besides traditional sources, had collected versions of Dhatusena-Kasyapa history or story from contemporary villages around Sigiriya which had helped elucidate what is unclear or unsaid in the Mahavamsa. He had also tried to blur the distinction between the kind of history represented in the Mahavamsa and the tradition of story-telling. But he admits that he cannot vouch for its veracity except being speculative.

"he approaching old age, the growing up of his daughters, the increasing realization of his painful conscience probably induced him to move to penance and self mortification and from one form of edifice construction to another, a more Buddhist one"

Obeyesekere uses a Chinese source to argue the fact that Kasyapa’s reign lasted only eighteen years. His evidence is a reference in a Chinese chronicle which reveals that there was another embassy from the island to China sent by “King Kia-che,” i.e. Kasyapa in 527CE. Wilhem Geiger had disagreed that the reference was of Kasyapa 1 because according to Mahavamsa, Kasyapa reigned from 478-496CE and 473-491CE according to the chronology of Sri Lankan scholars.

Whereas, Obeyesekere, agreeing with the Chinese sources says that it was perfectly possible for Kasyapa to have been alive, if not well in 527CE. The later date also fits in with the inference from the Mahavamsa that Kasyapa practiced “dhatunga” (extreme ascetic practices) in his old age. “A long reign is not only consonant with the psychology of the parricide ……… but fits in well with the conventions of practical Buddhism when renunciation and ascetic practices in old age are normative.”

Therefore, Obeyesekere proposes that it is Mugalan’s date that needs revision and perhaps one must take seriously the popular view that Mugalan went back to India after his brother’s death. If indeed Kasyapa and Mugalan fought a battle as Mahavamsa asserts, then it was an unequal war with Mugalan confronting a tired, old man, who had already given up his worldly ambitions and feeling guilty of parricide had given to extreme ascetic practices and meditation on the Brahma viharas (appamana.) The suicide of the King, confronted with the return of the brother, psychologically, the return of the father, makes sense in terms of the conscience of the King and his encroaching old age.

Therefore, Obeyesekere proposes that it is Mugalan’s date that needs revision and perhaps one must take seriously the popular view that Mugalan went back to India after his brother’s death. If indeed Kasyapa and Mugalan fought a battle as Mahavamsa asserts, then it was an unequal war with Mugalan confronting a tired, old man, who had already given up his worldly ambitions and feeling guilty of parricide had given to extreme ascetic practices and meditation on the Brahma viharas (appamana.) The suicide of the King, confronted with the return of the brother, psychologically, the return of the father, makes sense in terms of the conscience of the King and his encroaching old age.

And the author adds that if Kasyapa’s reign was longer, that makes the construction of Sigiriya during his lifetime much more plausible.

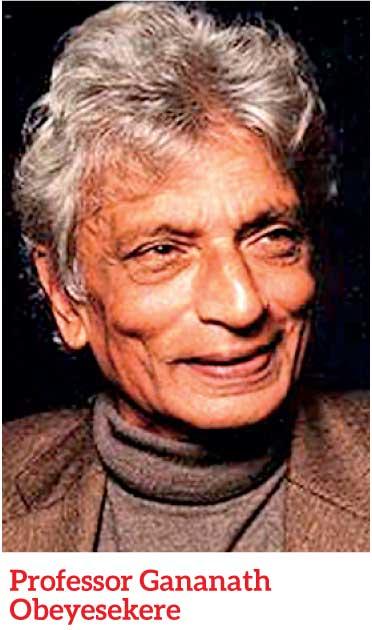

Under “The Two Kings” in Mahavamsa, Dhatusena had two sons –Kasyapa born of a mother of unequal birth while Mugalan (Mogglana) and a daughter were by a mother of equal caste. Obeysekere’s findings from village folks relate the story of Dhatusena’s amour with a woman of the Tamil community in his earlier years from whom he had Kasyapa, her death, his subsequent marriage to a Sinhala woman whose son was Mugalan and the step mother’s discrimination against Kasyapa. According to Mahavamsa, the architect of his parricidal act was Migara. Reading between the lines of the Mahavamsa, the author writes: the King had cold shouldered him, his cross-cousin later in life. Migara’s construction of a pirivena named after himself placed with an image of the Buddha, was denied a ceremony of consecration by Kasyapa. Migara bided his time waiting for the coming of the rightful ruler Mugalan.

What of the complex system of fountains and pleasure gardens that was a significant part of the Sigiriya landscape? Was it an expression of the King’s delight in sensual and aesthetic pleasures? And Sigiri graffiti refer to the King enjoying sensual pleasures with divine damsels. (Paranavitana 1956) Obeysekere’s assumption however is that Kasyapa’s all-consuming identification was with the parricide ancestor Sinhabahu.

Also, the King’s palace being on the very top of the rock was completely unrealistic, according to the author for normal living and kingly duties. But it expresses a meeting of geography with cosmology. Obeysekere however says that it has to be left open to understand whether the King, perched on his palace atop, surveyed the world as it unfolded although there is no way that one can confirm this hypothesis.

Kasyapa’s life of hedonism was a way of overcoming the guilt of parricide or rather not permitting guilt to surface by embracing the pleasure principle and living like a divine king enjoying the life of senses.

The question then is whether we can reconcile the life of pleasure of imitating the cosmos with its very opposite life of penance alongside the idealized Brahma viharas and the King’s latter day open espousal of Buddhism?

“……………..the approaching old age, the growing up of his daughters, the increasing realization of his painful conscience probably induced him to move to penance and self mortification and from one form of edifice construction to another, a more Buddhist one.”

Mahavamsa mentions that Kasyapa restored and expanded the great temple of Isurumuniya in Anuradhapura and named the temple after his two daughters and his own – “Isuramenu Bo-Upulvan-Kasubgiri (Kasyapa of the mountain.)