Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

This new work is a departure from that biographical vein. The resurgence of Ravana literature in recent times, mainly in the Sinhala newspapers, should be interpreted as an attempt to place today’s strident Sinhala nationalism in a romantic, glorified setting

Dr. Arthur Clarke stated categorically that astrology is not a science. Science or not, astrology has millions of followers, and not just in Asia

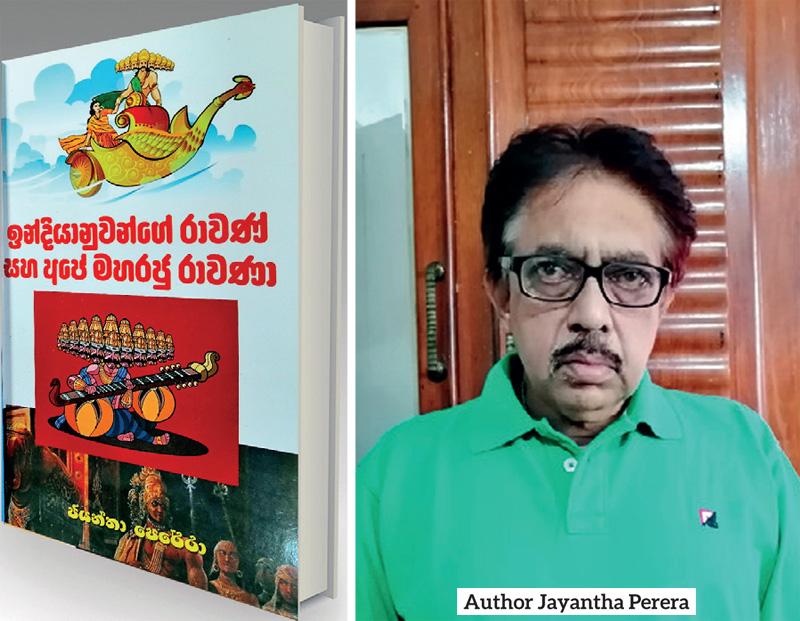

‘Indianuwange Ravana and our King Ravana’ is the title of the third book by Jayantha Perera. His previous two biographical works dealt with his life experiences, from his time in Italy and Britain as a very young man, to growing maturity and professional disillusionment as a tourist guide lecturer back in Sri Lanka.

This new work is a departure from that biographical vein. The resurgence of Ravana literature in recent times, mainly in the Sinhala newspapers, should be interpreted as an attempt to place today’s strident Sinhala nationalism in a romantic, glorified setting. Ravana wasn’t Sinhalese as his story is a pre-Vijayan tale of fantasy and adventure to rival the Arabian nights (minus the erotic parts).

This new work is a departure from that biographical vein. The resurgence of Ravana literature in recent times, mainly in the Sinhala newspapers, should be interpreted as an attempt to place today’s strident Sinhala nationalism in a romantic, glorified setting. Ravana wasn’t Sinhalese as his story is a pre-Vijayan tale of fantasy and adventure to rival the Arabian nights (minus the erotic parts).

But then, shouldn’t every upright Sinhalese be proud of an ancient demon king who flew aircraft and took on mighty India? Or so seems to believe every writer, who has resurrected the Ravana mythology in our newspaper pages. In any case, the idea that the Sinhalese too, can be equal to the best of demons (at least when it comes to politics) is a believable hypothesis.

Kinship, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. In India, certain Tamil groups love Ravana for a different reason – those who think that the Ramayana is an example of the Sanskritisation and cultural dominance of the South by the North and others that the story stands for northern political domination of South India admire Ravana for what he did.

Jayantha Perera does not indulge in hero worship, though his admiration for the demon king is plain. The difficulty for the reviewer is this: Is this a work of fact, or fiction? Like with other durable and endearing myths (the story of Atlantis, for example), there hasn’t been a shred of archaeological evidence to support Valmiki’s Ramayana, the source of the Ravana myth.

For those who want us to believe in myths, the field of cult archaeology is wide open and tempting. The 1968 bestseller Chariots of the Gods by Eric Von Daniken is a good example, in which the author tried to convince readers that extra terrestrials visited the earth thousands of years ago. He presented as evidence drawings by pre-historic cave dwellers and giant rock sculptures with the claim that some of these figures represented astronauts and spacecraft. But nothing was ever proven except that the author had a bustling imagination.

There isn’t even a cave drawing either here or in India to support the Ravana story, but many continue to believe that Ravana is a historical figure and the events narrated in the Ramayana, such as the kidnapping of Sita by Ravana and the subsequent war, have some historical basis. The name of both Sita and Ravana are associated with several geographical locations in the Island. But there is no supporting evidence.

Lack of evidence, as those in the legal profession surely know, does not mean the story isn’t true. The lack of a Ravana section in the national museum does not prevent us from enjoying this book. Jayantha Perera does not pretend to be scholarly. Instead, being an astrologer, he looks at the demon king from that angle. While he does not provide us with a comprehensive bibliography, the author quotes from sources such as the Mahawamsa (the Greater Chronicle). Since there are many who accept its mythological passages as part of a valid historical narrative method, the reader may feel a compulsion to accept the author’s astrological explanations in the

same spirit.

Whether one believes in astrology or not, this makes fascinating reading. One can’t help recalling David Frawley, who came to India as a young American to study Vedic astrology, married an Indian, became Hindu and is now part of the Hindutva movement. His early books such as ‘The Astrology of Seers’ provide fascinating reading, and he offers the birth charts of many historical figures ranging from Mahatma Gandhi to Adolf Hitler. While Frawley’s Hindutva associations including the Hindu far right are less appealing, there is no denying that his works on Vedic astrology are interesting reads. Scholars, both Indian and Western, dismiss the idea that Frawley is a scholar, and say that his books have popular appeal.

Jayantha Perera’s book, too, should be read with the same mindset. When Frawley speaks of the Asuras, is he talking fact or fiction? Dr. Arthur Clarke stated categorically that astrology is not a science (Dr. Abraham Kovoor would have given an interesting answer to that question). Science or not, astrology has millions of followers, and not just in Asia. There is a Western branch of astrology too, though one doubts if either Donald Trump or Joe Biden counted on astrologers ---being mercurial, Trump just might if he decides to go for the White House again.

Even astrology’s detractors would be hard put to deny that astrology is therapeutic. While astrologers do not always offer happy endings, they know how to deliver the bad news. This may be one reason why Sri Lankans have no faith in psychiatry. While the psychiatrist can turn one’s grandmother into a demon, the astrologer puts the blame squarely on planets in collision.

When Jayantha Perera details the birth dates, stars and planetary dispositions of Rama, Ravana and their eventful times, he sounds eminently believable. Unlike astronomy, which requires sleepless nights with eyes glued to telescopes without giving anyone a clue as to what fate is all about, astrology gives a short or long term progress report of future and past events based on planetary conjunctions. Therein lays the charm of astrology compared to the number-crunching boredom of astronomical science.

Anyone who believes in astrology can easily believe in UFOs and ‘Chariots of the Gods’ would be good bedtime reading for such people. When I began reading Jayantha Perera’s book, my mindset was agnostic, as it has always been. But, a couple of chapters into it, I almost believed in gods and demons. Eventually, the skeptic in me gained control. Did Atlantis really exist? Most probably, Plato made it up. But one should be glad he did, for history would be barren without an Atlantis, a mysterious, romantic, lost continent and civilization. The story of Ravana has retained its best-seller quality down the centuries and Jayantha Perera has grasped this point well in his narrative.

According to him, Ravana had a good knowledge of astrology. Didn’t he see what was in store for him? Perhaps he thought he could take on the stars, and win. What matters is not whether Ravana really had ten heads or if he had a flying machine or if he existed at all. What’s fascinating is how he could get into 21st century minds and stay there, and that’s why this book is such a good read, even if one would be better off taking it as fiction and not fact.