Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Some prefer to call it a religion, while others call it a philosophy, still others regard it as both a religion and philosophy, as it contains many characteristics

Buddhism originated in India in the 6th century BC. Today Buddhism has become one of the most popular religions with over 507 million followers worldwide. It is a non-theistic religion, as it does not believe in a creator or God.

it does not believe in a creator or God.

Some prefer to call it a religion, while others call it a philosophy, still others regard it as both a religion and philosophy, as it contains many characteristics which blur the lines between philosophy and religion.

Different people view Buddhism differently. Therefore, the question of whether Buddhism is a philosophy or a religion depends on how people define religion and its technicalities.

Religion generally connotes the idea of the presence of a powerful God who controls the entire world, non-theistic Buddhism cannot be classified as a religion. Term non-theistic religion would be a contradiction in terms.

Of course, it has to be admitted that there are plenty of religious and philosophical aspects to Buddha’s doctrine.

Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama the Buddha. He was born to a royal family in Kapilavastu, on the foothills of the Himalayas in the 16th century B.C. When he was overcome by sights of disease, old age and death he realized that the world was full of suffering and misery and therefore renounced his worldly life in search of true happiness. After practising great austerities, and going through intense meditation with a strong will and a mind free from all disturbing thoughts and passions, he attained enlightenment.

The Buddha can also be regarded as one of the greatest psychotherapists the world has ever produced.

Buddhism is a pragmatic teaching, which starts from certain fundamental propositions about how we experience the world and how we act in it. It teaches that it is possible to transcend this sorrowful world and shows us the way of liberating ourselves from the sorrowful state.

Buddhism is not culture-bound, nor bound to any particular society, race or ethnic group, unlike certain religions that are culture-bound. Buddhism believes in pragmatism and its practicality can be seen as one of its distinguishing features. Buddhism lays special emphasis on practice and realisation.

In a way, Buddhism can be considered a way of life a righteous way of life which brings about peace and happiness. It is a method of ridding ourselves of miseries and finding liberation from samsaric cyclic life.

The teachings of the Buddha contain practical wisdom that is not limited to theory or philosophy. Philosophy deals mainly with knowledge and it is not concerned with translating that knowledge into day-to-day practice.

Philosophy is commonly defined as a rational investigation of principles and beliefs of knowledge and conduct. Philosophy can see the frustrations and disappointments of life but unlike Buddhism, it does not show any practical solution to overcome those problems which are part of the unsatisfactory nature of life.

The Buddha’s teachings are referred to as the Dhamma, which means ‘the ultimate truth’ or the ‘truth about reality. Buddhists are expected to live by it. The Buddha always encouraged his followers to investigate his teachings for themselves. His Dhamma is described as Ehipassikko which roughly means “Inviting his followers to come and see for themselves or verify or to investigate.

He strongly encouraged his followers to engage in critical thinking and draw on their own personal experiences to test what he was saying. This attitude differs entirely from other religions such as Christianity where followers are encouraged to accept its scriptures unquestioningly. This is exemplified by the Kakama Sutra.

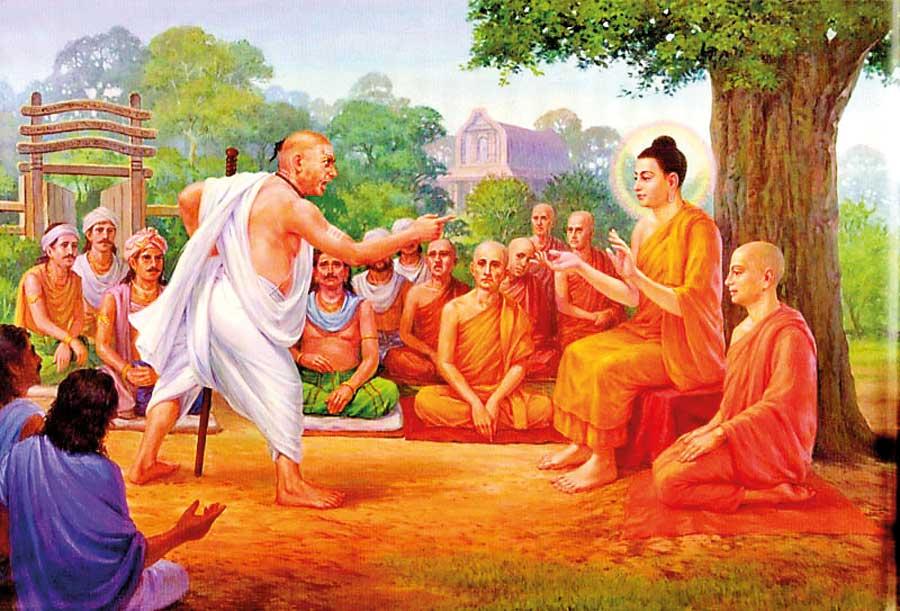

When the Buddha on his wanderings arrived at Kesputta, the town of the Kalamas, the Kalamas went to the Buddha and said to the Buddha

“Lord, there are some Brahmins and ascetics who had come to Kesputta. They expound and glorify their own doctrines but as for the doctrines of others, they deprecate them, revile them show contempt for them and disparage them. Then again other Brahmins and ascetics come to Kesputta they too expound and glorify their own doctrines, but as for the doctrines of others, they deprecate them, revile them show contempt for them and disparage them. They leave us absolutely uncertain and in doubt. Which of these venerable Brahmins and ascetics are speaking the truth, and which ones are lying?

Lord Buddha in reply said:

“Yes, O Kalama’s, it is right for you to doubt, it is right for you to waver. In a doubtful matter, wavering has arisen.”

And the Buddha gave them the following advice.

“Come, O Kalamas, do not accept anything on mere hearsay. Do not accept anything by mere tradition thinking that it has been handed through many generations. Do not accept anything on account of rumours without investigations. Do not accept anything just because it accords with your scriptures. Do not accept anything by mere supposition. Do not accept anything by mere inference. Do not accept anything by merely considering appearances. Do not accept anything merely because it agrees with your preconceived notions. Do not accept anything merely because it seems acceptable. Do not accept anything thinking that the master is respected or it is part of the tradition.”

“But when you know for yourselves after an investigation that these things are good, these things are not blameless, these things are praised by the wise, undertaken and observed, these things lead to the benefit and happiness, enter on and abide in them”

These wise utterances of the Buddha made more than 2,500 years ago, still hold good.

“As the wise test gold by burning, cutting and rubbing it on a piece of touchstone, so are you to accept my words after examining them and merely out of regard for me.”

The Buddha dealt with the problem of human suffering and approached it concretely.

This attitude of pragmatism in Buddhism is evident from the Culamalukyasutta in which the Buddha made use of the example of the wounded man.

A man wounded by an arrow wished to know who shot the arrow, from which direction it was shot, and the material with which it was made before it was removed from his body. This man is compared to a man who would like to know about the origin of the Universe, whether the world is eternal or not, finite or not before he practices the religion.

Just as the man in the parable will die before he has all the answers he wanted regarding the origin and the nature of the arrow, such people will die before they will ever have the answers to all their irrelevant questions. This Sutra exemplifies the practical attitude to Buddhism and the question of priorities.

Buddha as a primarily ethical teacher and reformer discouraged metaphysical discussions devoid of ethical value and practical utility. Instead, he enlightened his followers on the most important questions of sorrow, its origin, its cessation and the path leading to its cessation, as adumbrated in the Four Noble Truths. To him, the problem of human suffering was much more important than speculative discussions or reasoning.

Buddhism is not a religion based on faith, authority, dogmas or revelation, but based on facts as we experience them in our daily lives. Buddha declared “whether a tathagata (buddha) arises in the world or not, all conditioned things are transient” (Annica), unsatisfactory (Dukkha) and soulless (Annatta).

He declared deliverance could be attained independent of any external agency such as a God or a saviour. This is one of the fundamental differences which distinguish Buddhism from other religions.

In the Dhammapada the Buddha says:

“By oneself alone is evil done: by oneself is one defiled. By oneself alone is evil avoided: by oneself alone is one purified. (Purity and impurity depend on oneself. No one can purify another). A Buddhist does not think that he can gain purity or salvation merely by seeking refuge in the Buddha or by mere faith in him. Buddha as a teacher may be instrumental or show the path of purification to a person but he himself has to strive.

Although the Buddha discounted the concept of God he never denounced or denigrated it. Never in all his discourses did the Buddha make a direct attack on the concept of God.

The Buddha speaks of the law of karma which he uses to expound on the unfairness and inequality that exists in society, the defilements, fetters and hindrances such as attachment, sensory desires, lust, doubt and uncertainty and craving which prevent one from attaining liberation from samsaric life. All of the above goes to prove the religious aspects of the doctrine. The five precepts by Buddha are more like a set of guidelines people should follow for a good life in this and the next life.

Therefore, the debate whether Buddhism is a religion or a philosophy is legitimate as both sides have a reasonable argument to buttress their stand on the matter.