Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

In Jayawardene’s book, was nothing less than taking the surveys and sketches of the period from 17th century to 19th century Sri Lanka

the book asks us to examine the nature of elite formation in the Sri Lankan context. What’s pertinent is that there was no one elite class, but several intermediate ones

Jayawardene’s work must be read in conjunction with the books, the essays, and the archival material of other writers

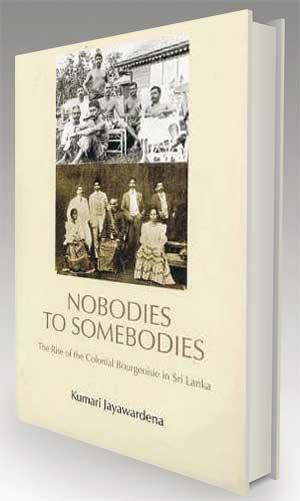

When Kumari Jayawardene wrote and published Nobodies to Somebodies at the beginning of the millennium, there were howls of protests from two separate though interrelated camps. First and foremost, there were the descendants of the families whose histories she had painstakingly sketched out.

They were irked at what they felt to be her attempt at tarnishing their image by claiming that their ancestors were involved in the arrack trade.

I remember a descendant of the De Soysa family once telling me that Ms. Jayawardene effectively undermined all the good work that these capitalist entrepreneurs had done. It was hard not to disagree with that thought, until you realise that most, if not all, of these entrepreneurs built the schools, hospitals, churches, temples, and other public institutions that they did because of two cardinal reasons: they were earning profits at a rate unprecedented in our history, and the profit they earned was not taxed. In other words, there was a lot of money lying around the corner, and not much that could be done with it even after channelling it to perpetuate the family wealth.

What Jayawardene did with her book was nothing less than taking the surveys and sketches of the period from 17th century to 19th century Sri Lanka, by writers such as Patrick Peebles and Michael Roberts, forward. Until Nobodies to Somebodies the emphasis on elite formation in this period had been on caste: the rise of the karava over the traditional govigama elite. Jayawardene took these surveys even further, and examined what Jayadeva Uyangoda referred to as the colonial caste system. It was an intrepid study of how the colonial machinery, instead of doing away altogether with the occupation-based caste system, retained certain elements of it while restructuring, if not obliterating, most other pre-colonial institutions and structures.

If this is all she did, Nobodies to Somebodies may have been a masterpiece on its own right. But she didn’t stop there. She took up from where she had paused in her earlier work, The Rise of the Labour Movement in Ceylon, to analyse the cleavages between the different sections of the elite in British Ceylon.

It was there that her scholarship and penchant for research cropped up discernibly, and it was there that she managed to irk those descendants of the families she sketched out.

The Rise of the Labour Movement had only briefly engaged with the bourgeoisie. Nobodies to Somebodies, by contrast, went into not just how the bourgeoisie rose up and prospered, but what they did in their everyday lives. One of her references was Arnold Wright’sTwentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon, but as she pointed out in a later essay, the people listed in it “paid to have their family histories mentioned.” She made up for the limitations of these sources by her own probing; in the tenth chapter, a series of sketches of elite families, thus does more than regurgitate old texts.

The 18th and 19th centuries were a period of intense shifts and transformations in this country. The Portuguese and the Dutch had, as scholars have pointed out, been merely content with mildly reforming local administrative structures to suit their needs. As with the British, with them also commercial and military interests preceded religious, social, and cultural considerations. But the advent of the British brought here with it something different. It’s hard to explain what that was without recourse to the changes that were being wrought on European society during the Industrial Revolution and the victories won by the British during the Napoleonic Wars.

The 18th and 19th centuries were a period of intense shifts and transformations in this country. The Portuguese and the Dutch had, as scholars have pointed out, been merely content with mildly reforming local administrative structures to suit their needs. As with the British, with them also commercial and military interests preceded religious, social, and cultural considerations. But the advent of the British brought here with it something different. It’s hard to explain what that was without recourse to the changes that were being wrought on European society during the Industrial Revolution and the victories won by the British during the Napoleonic Wars.

The economy the British conquered was inadequate to the achievement of their objectives. As Patrick Peebles has pointed out, “The amount of money in circulation in the domestic economy of 19th century Sri Lanka was small.” The British initially “did little to encourage its growth”, but with the annexation of Kandy, a plantation sector dependent on investment, labour, and foreign ancillary services such as banking compelled a radical restructuring of the economy. This encouraged the growth of a primitive primary sector. Almost nothing else concerned the colonial office, so much so that Edward Barnes, who placed emphasis on infrastructural projects, was openly hostile to missionaries who tried to set up schools in the country.

Barnes, however, was not an advocate of the laissez-faire economy that Colebrooke and Cameron would later usher into the island. His views were decidedly statist, if not mercantilist: for him even the plantations were “not sufficiently valuable to attract European speculators.” Jayawardene here goes to point at the two most significant events that facilitated a take-off for those speculators and local capitalists: renting on a tavern basis being replaced by renting on an administrative basis, and the prohibition against headmen (vidanes) taking part in the arrack trade (by then a booming sector), both decreed in 1832. She speculates, correctly, that this is what led to the fall in the number of govigama arrack rentiers over the decade.

I have in another essay sketched out, in a basic form, the nature and the characteristics of the elite that emerged from the boom in the arrack and plantation trade. What needs to be pointed out is that they were only partly allowed into the administration of the country; as Jayawardene has noted, banking facilities were limited to foreign planters, which had the effect of preventing the local capitalists from maturing to the industrial sector. With very few options left, the elite naturally invested in the few crops they were allowed to: coffee, tea, graphite, rubber, coconut, and arrack.

It is here that the contradictions in the period delved into in Nobodies to Somebodies begin to emerge. And it is here that the book asks us to examine the nature of elite formation in the Sri Lankan context. What’s pertinent is that there was no one elite class, but several intermediate elite classes.

Contrary to the later dichotomies drawn between these milieus, these were not always opposed to each other.

They were the front-runners and the leaders of the Buddhist, Hindu, and Muslim revivals; they were the founders of the trade union movement in the country; they were the first agitators for ethnic separatism.

The conflicts between them did emerge with the rise of the labour movement, but even then it’s difficult to generalise and say that they were perpetually against one another.

It must be pointed out that to appreciate the complexities that were the defining hallmark of this period in history, Jayawardene’s work must be read in conjunction with the books, the essays, and the archival material of other writers.

To understand the intricacies of the Buddhist revival, it is imperative to read Kitsiri Malalgoda’sBuddhism in Sinhalese Society. To understand the role played by the women in these movements, it is imperative to read Jayawardene’s studies of third world feminism and Manel Tampoe’s extensive biography of Celestina Dias.

Nobodies to Somebodies, unlike certain books in the genre, was consequently not a mere compilation, but a reference point that took from, and supplemented, other material. It’s hard to categorise a work like it because it belongs to so many fields and disciplines: sociology, economics, history, economic history, even literature.

The late S. B. D. de Silva, who read through the first drafts of her work, once noted, “Writing is less a matter of language than logic, connecting one idea to another.” In that sense Jayawardene’s study is as logical as it is literate; it is not a flawless study (among those flaws, it perpetuates the same kara-govi caste conflict discourse it sought to go beyond), but it is certainly free from the generalisations and the simplifications that characterise the genre. At a time when the rentiers are back in power, we need to read it, to understand it, to appreciate it, so as to come to terms with the reality of our economic, social, and cultural debacle.

I mentioned that there were two camps that opposed the publication and sale of Nobodies to Somebodies. The first, the descendants of the rentiers, I have detailed.

The second camp is more complicated and complex: the nationalists. Why and how they were (and are) against the book merit a separate essay, to itself.

The author can be contacted on