Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

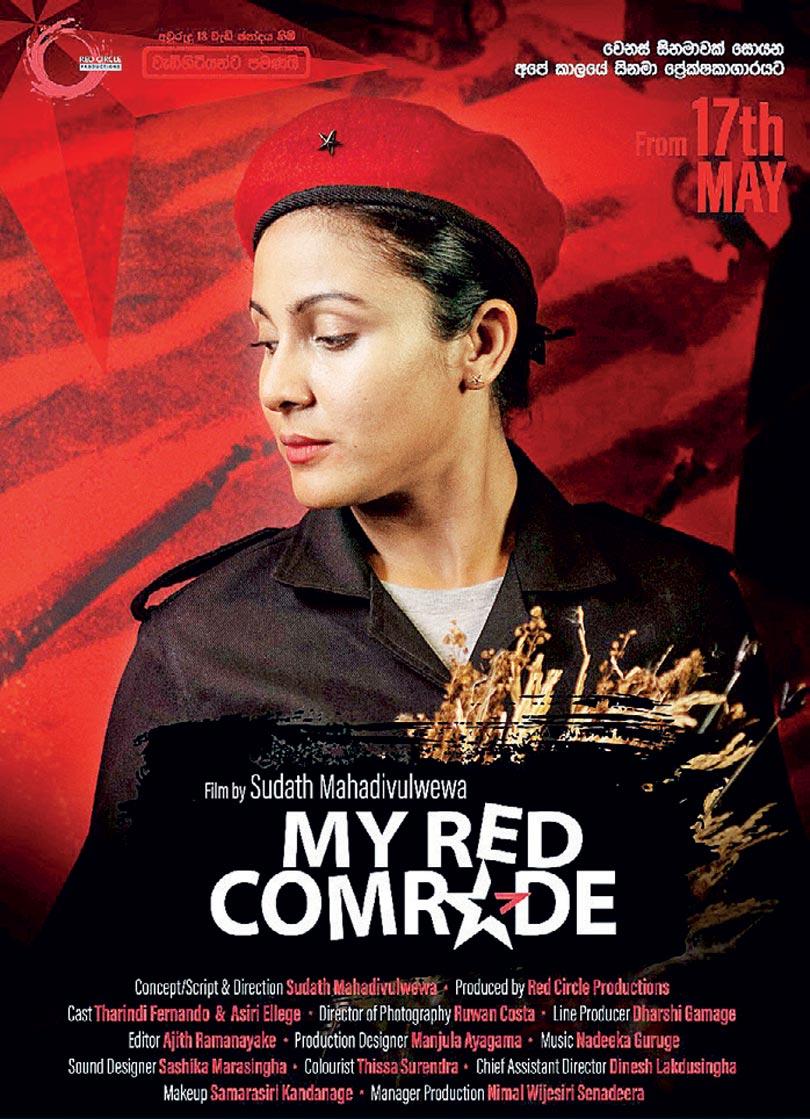

My Red Comrade” makes a critical contribution to the society

Sudath  Mahadivulwewa’s latest film, now in cinemas, is openly political and experimental. A major aspect of the film is a debate between the old view of revolution and a more modern one

Mahadivulwewa’s latest film, now in cinemas, is openly political and experimental. A major aspect of the film is a debate between the old view of revolution and a more modern one

Sudath Mahadivulwewa, the producer of the film ‘My Red Comrade’, is well-known for his various feature films, documentaries, theatre work and social awareness campaigns, in Sri Lanka. His latest film is openly political and experimental. A major aspect of the film is a debate between the old view of revolution and a more modern one which is construed to be more inclusive. The film conveys a message “think simple as a child, and do not make things more complicated than necessary”. To demonstrate this, the film uses a Native American fable about a wolf. How the wolf gets into us from the environment we are brought in; an environment in which we receive our education, the media we are exposed to and the conscious choices we make: The moral of the tale being what wolf to feed and what wolf we must reject. It appears to have been used as a metaphor for capitalism which has destructively transformed the extraction and exploitation of the environment and human beings.

Considering the environment the vast majority of people labour under, what are the political social issues springing from that inequitable and destructive system that the protagonists of the film debate on? The title of the film itself denotes that it will be about the Left. The very first scene confronts us with the repressive state apparatus and its victims. Without overwhelming us, the scene expertly draws our attention to think about these issues. The film commences with a scene where the main female character is subject to a hunt by the police. To avoid capture she hides in an unknown dilapidated slum like dwelling occupied by a middle-aged man. The sounds employed heightens and enhances the drama taking place. By this astute use of sound, lighting and props, My Red Comrade confines its narrative and action to a night in a simple one-bedroom dwelling; taking us to a complex and problematic night with a myriad of survival situations; predicated by an inherently radical communal humanism. The leaking water from the roof falling onto pots on the floor depicts the social status of the inhabitant itself. The intense rain may denote the effects of climate change. The male occupant with his long-dishevelled hair and unruly beard is reminiscent of the portraits of Marx. He is a typical vivid reader and writer with a large collection of books with proficiency in the use of a laptop, a scooter and a mobile phone. It brings to mind the archetypical well-read leftist political activist. Maintaining an extensive ‘library’ under a run-down leaking roof of a shanty town is unrealistic, heightened by a Soviet era poster. Not what you would expect of a clandestine journalist collating material for articles and fighting against the government. Nevertheless, they can be considered necessary props for some of the debates on what it entails to be a leftist. She expects the well-read ‘leftist’ (the Red Comrade) to believe in an equal society and aspire to build a better world; to be a kind-hearted person. But his behaviour belies his political beliefs. He does not look at her when she addresses him and demands her to vacate the place. He, who dreams of a decent world of equals, thinks highly of himself compared to others, and expects respect and deference from others. He continues to be rude to her. His character displays a contradiction: initially of a rigid rudeness and disrespect and later being compassionate and of flexible politeness, towards the girl who is wet and shivering with cold. After making coffee he sees her sitting on his chair and barks at her: “why did you sit on my chair”. She becomes irritated and asks whether the chair is a throne. He shows no kindness, until he finds out about her desperate situation. Ultimately, he persuades her to remain maintaining that it is yet raining outside, and the police may be still in the vicinity. After hearing her story of how her mother had left her father and how he looked after her without letting her feel the absence of her mother in her life; and later, how her father was killed by the security forces, he offers his chair. He proposes to her to cook dinner for both of them. Nevertheless, there is only one plate. They discuss the choices they can make in an understanding and compromising manner. Ultimately, they agree to share the same plate. Then, he proposes to have a chat and she becomes more sociable. She takes the black and red coffee mugs he had brought and offers the red mug to the Red Comrade. One wonders whether the scene depicted the cultural inhibitions in a proper manner. Such an attitude may have been generated by many factors, though the impression I got while viewing was that of a typical male comrade who is committed and dedicated to their cause, but is still prejudicial against women. The disparity and distance between the two are depicted with the girl looking outside while he is looking at her. Later in the film, this comes out clearly during many scenes, when “the comrade” says ‘women do not understand it” and when the girl shouts back – but you have no room for women like me in your equal society. He stubbornly continues to underestimate the strength and commitment of the young woman.

He

|

Filmmaker Sudath Mahadivulwewa |

receives a warning, that the security forces are on to him, but does not want to tell her; believing that she cannot be of any help. He asks her to leave to avoid getting arrested. If she were not there, he could have left the place immediately, but they cannot leave as the police have surrounded the area. She questions why. Is it because being arrested with a girl at his house would ruin the chastity of his left politics? He is adamant that there are no “us” here, yet both are to be arrested under the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act. At first, she lied, when asked a question and then she went to the extent of stating: “My family believes that I am doing a good job”. She does this as she thought nobody would understand her story. She refuses to leave, but thinks of a way that would save them both. Then she reveals her real role that she is a performing artist. To save them both from being arrested by the police, she impersonates a sex worker. The police then leave thinking that she is in fact a sex worker. The sadistic nature of state repression and the degradation of the legal system is starkly illuminated when she says the police would place a packet of drugs, to keep her in custody for at least six months. A tacit understanding is illustrated, when the girl with a liking towards the library of books movingly reveals what happened to her father, an avid collector and reader of progressive Russian literature. Her father’s influence on her become clearer when she recites certain paragraphs with lines like: “a person is a slave from birth unto death”. These words are from Maxim Gorky’s Makar Chudra short story book that her father had. Both characters are committed to the same political vision, but did not know each other until they met accidentally due to a police pursuit. They fought for the same dream, but the state killed the dreamers of the nation; creating a country without dreamers in the process.

A film needs to reflect the social and political concerns of the era in which it is made. The disparity between what the two characters identify when listening to the rain with their eyes closed shows how close they are to reality. The girl hears natural sounds; however, what the Red Comrade hears is his feelings: like a child crying while a mother is singing a lullaby, or a man and a woman fighting with each other. Gradually the man also comes to hear the natural sound of rain. The girl asks how the comrade missed the sound of the rain which they were both experiencing. Obviously, the comrade has heard the rain but not listened to it. This is symbolically depicted as the reason revolution did not succeed in Sri Lanka.

She emphatically states that one cannot plant poplar trees brought from Russia in Sri Lanka. They need to suit the Sri Lankan soil.

Finally, both of them get together to light a candle to expel the darkness. The violent nature of state repression comes out movingly with her story. Her father was forced to move all books to the middle of the house. Then the forces poured petrol and set fire to the books. Then they shot her father; forcing him to fall onto the burning pyre of books. This evokes emotions reminding us of what the forces and politicians did during the three uprisings in the island; particularly when they set alight the Jaffna library. She mutters: “In Russia those who read those books made the revolution and in Sri Lanka, they were killed.”

The film also portrays the post traumatic distress disorder (PTSD) Sri Lankan society is under.

In my view, the film “My Red Comrade” makes a critical contribution. It is an independent film taking a more realistic approach rather than a melodramatic formalistic one - though certain episodes at various points appear to break that sense of reality.

This is an excellent film, with fine direction, a masterful script with skilful use of sound and lighting and impeccable performance from the leads which are both naturalist and moving. It is a commendable and brave experimentation in filmmaking.

(The writer was a 1972 senior JVPer and now

an academic in Australia)