Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

In the past, whatever government that secured power, focussed on providing subsidised fertilizer, pesticides and other inputs apart from waiving farmers’ loans and promising better prices for agricultural products

In the past, whatever government that secured power, focussed on providing subsidised fertilizer, pesticides and other inputs apart from waiving farmers’ loans and promising better prices for agricultural products

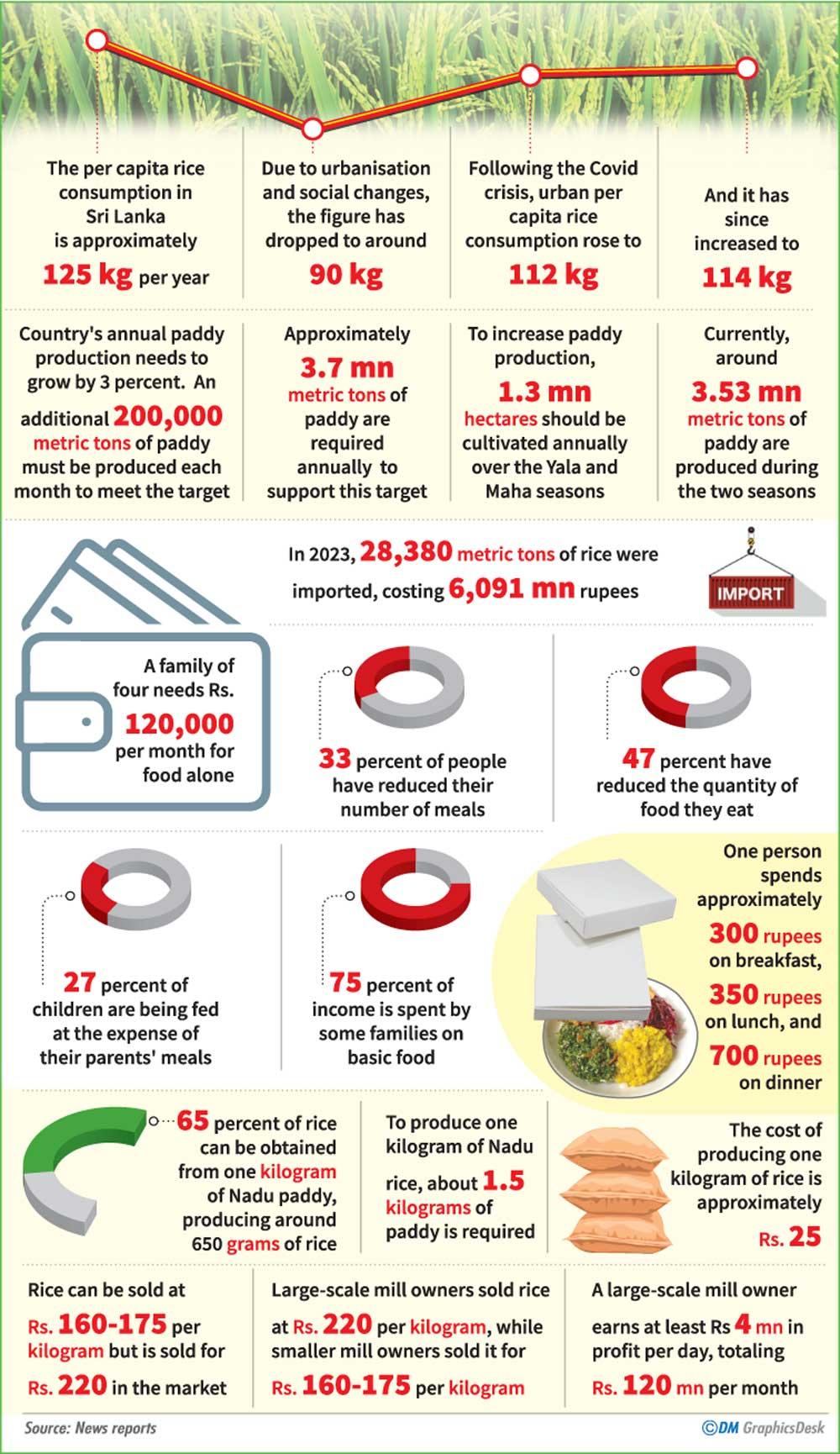

If Sri Lanka was self-sufficient in rice, there would be no need to import even a single grain. Yet, in 2023, 28,380 metric tons of rice were imported, costing 6,091 million rupees. Despite this, in January 2024, former Agriculture Minister Mahinda Amaraweera claimed that the country was self-sufficient in rice

The per capita rice consumption in Sri Lanka is approximately 125 kg per year. However, due to urbanisation and social changes, the figure has dropped to around 90 kg with regard to some people. Following the Covid crisis, urban per capita rice consumption rose to 112 kg, and it has since increased to 114 kg. This represents an annual increase in per capita rice consumption of about 1.1 percent. Consequently, the country’s annual paddy production needs to grow by 3 percent. According to former Director of Agriculture, K. B. Gunaratne, to achieve this target, an additional 200,000 metric tons of paddy must be produced each month; totalling 2.4 million metric tons annually. Furthermore, to support this target, approximately 3.7 million metric tons of paddy are required each year. Most of the facts and figures supporting this article have been derived from a conversation this writer had with Gunaratne.

The per capita rice consumption in Sri Lanka is approximately 125 kg per year. However, due to urbanisation and social changes, the figure has dropped to around 90 kg with regard to some people. Following the Covid crisis, urban per capita rice consumption rose to 112 kg, and it has since increased to 114 kg. This represents an annual increase in per capita rice consumption of about 1.1 percent. Consequently, the country’s annual paddy production needs to grow by 3 percent. According to former Director of Agriculture, K. B. Gunaratne, to achieve this target, an additional 200,000 metric tons of paddy must be produced each month; totalling 2.4 million metric tons annually. Furthermore, to support this target, approximately 3.7 million metric tons of paddy are required each year. Most of the facts and figures supporting this article have been derived from a conversation this writer had with Gunaratne.

To increase paddy production, 1.3 million hectares should be cultivated annually over the Yala and Maha seasons. Currently, around 3.53 million metric tons of paddy are produced during these two seasons. Therefore, producing enough paddy to meet the country’s needs isn’t a significant challenge. Additionally, the government has maintained a surplus of paddy for the past three months. However, the last time Sri Lanka was truly self-sufficient in paddy was between 2010 and 2013. Since then, the country has not achieved self-sufficiency. The claims that are being made that the country is self-sufficient in producing paddy are misleading.

If Sri Lanka was self-sufficient in rice, there would be no need to import even a single grain. Yet, in 2023, 28,380 metric tons of rice were imported, costing 6,091 million rupees. Despite this, in January 2024, former Agriculture Minister Mahinda Amaraweera claimed that the country was self-sufficient in rice.

The current pattern of food consumption in Sri Lanka is in dire straits. This is largely due to the collapse of the economy. As a result, people have changed their diets and many have reduced the amount of food they consume. Those who once ate three meals a day now limit themselves to two or even one. Many are also resorting to food with little to no nutritional value. Parents often sacrifice their own meals to feed their children. This was confirmed by a survey conducted by ‘Learn Asia’ taking input from 4,000 families in 400 Grama Niladhari divisions in Sri Lanka. The survey found that 33 percent of people have reduced their number of meals, while 47 percent have reduced the quantity of food they eat. Additionally, 27 percent of children are being fed at the expense of their parents’ own meals.

Increase in food-insecure families

A recent joint survey by the World Food Programme and the Food and Agriculture Organization revealed that the number of food-insecure families in Sri Lanka has risen from 17 percent to 24 percent in just six months. This includes 51 percent of households in the estate sector, 51 percent in rural areas, and 15 percent in urban areas. Some families are now spending 75 percent of their income just to afford basic food. According to government statistics, a family of four needs 120,000 rupees per month for food alone. This raises serious concerns about how they are able to afford food.

Given the current situation, one person spends approximately 300 rupees on breakfast, 350 rupees on lunch, and 700 rupees on dinner. However, the food consumed lacks nutritional value. If this trend continues, the number of people affected by malnutrition and communicable diseases would increase.

To address this issue, providing rice at a subsidised price is essential for Sri Lankans. It is the responsibility and duty of a responsible government to do so. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka lacks a proper agriculture policy to implement such measures. In the run-up to the presidential elections- that concluded on September 21- all major parties made promises to the people that they cannot realistically fulfil. These political boastings give rise to a debate whether the agriculture policies promised pre-election would have been carried out effectively had the lawmakers serving the past cabinet survived this election.

It’s a fact that whatever the government that secures power, the focus is often on providing subsidised fertilizer, pesticides and other inputs apart from waiving farmers’ loans and promising better prices for agricultural products. However, there appears to be little emphasis on increasing food production through scientific methods. Additionally, none of these policies seem to address the need to protect consumers in the country.

What a government should do is prioritise measures that increase food production using scientific methods to meet consumer demands. When one kilogram of Nadu paddy is processed, around 650 grams of rice is produced. To produce one kilogram of Nadu rice, about 1.5 kilograms of paddy is required. Similarly, 64 percent of Kekulu rice, 63 percent of Samba rice, and 61 percent of Keeri samba rice can be obtained from one kilogram of their respective paddy types. The cost of producing one kilogram of rice, including expenses such as machinery, electricity, labour and distribution is approximately 25 rupees. Given the government’s guaranteed price of 100 rupees per kilogram of paddy, rice can be sold to consumers at 160-175 rupees per kilogram. However, in the current market, a kilogram of rice is sold for 220 rupees. The government should address this issue. If some relief is provided, rice could be sold to consumers for 150-160 rupees per kilogram.

Paddy milling costs

To provide rice at a lower price, the government could offer transportation facilities for rice distribution. Additionally, the paddy milling costs could be reduced by supplying milling machines to farmers’ organizations under the Department of Agrarian Development at subsidised prices. Strengthening these organizations would enable the government to create a system that supplies rice to the public at a subsidised rate. Countries like Japan, China, and Korea use modern rice milling machines, and similar machines are now being produced in Sri Lanka. By equipping farmer organizations with these machines, greater efficiency can be achieved.

The government should also facilitate the establishment of rice mills in the major paddy-producing districts such as Ampara, Batticaloa, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Kurunegala, Hambantota, and the Mahaweli B, C, L, and M zones. Alternatively, the best rice mills in South Asia, located in Hasalaka, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, and Ampara, should be reactivated. Hector Kobbekaduwa served as the Minister of Agriculture in the United Front Government that assumed power in 1970, with Sirimavo Bandaranaike as Prime Minister. He established the Paddy Marketing Board through Act No. 14 of 1971. The primary goal of the Paddy Marketing Board was to ensure a guaranteed price for farmers and offer consumers concessions at a fair price. The Paddy Marketing Board is one of the institutions capable of carrying out this task. Under this system, cooperative societies across the country purchased the rice harvest and handed it over to the Paddy Marketing Board’s warehouses. Private paddy mill owners were then tasked with milling the paddy for a fee, and the rice produced was returned to the Paddy Marketing Board. Mill owners were paid the milling fee and the transportation costs.

The government should also facilitate the establishment of rice mills in the major paddy-producing districts such as Ampara, Batticaloa, Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Kurunegala, Hambantota, and the Mahaweli B, C, L, and M zones. Alternatively, the best rice mills in South Asia, located in Hasalaka, Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, and Ampara, should be reactivated. Hector Kobbekaduwa served as the Minister of Agriculture in the United Front Government that assumed power in 1970, with Sirimavo Bandaranaike as Prime Minister. He established the Paddy Marketing Board through Act No. 14 of 1971. The primary goal of the Paddy Marketing Board was to ensure a guaranteed price for farmers and offer consumers concessions at a fair price. The Paddy Marketing Board is one of the institutions capable of carrying out this task. Under this system, cooperative societies across the country purchased the rice harvest and handed it over to the Paddy Marketing Board’s warehouses. Private paddy mill owners were then tasked with milling the paddy for a fee, and the rice produced was returned to the Paddy Marketing Board. Mill owners were paid the milling fee and the transportation costs.

Following this, the distribution of rice across the country was managed by the Food Department. However, at present, the Food Department no longer exists, cooperative societies are defunct, and the Paddy Marketing Board has become a slow-moving institution. As a result, consumers no longer receive rice at subsidised prices. During that time, the Paddy Marketing Board had both numerous warehouses and its own paddy mills. Today, these facilities have degenerated. The ‘rice monopoly’ could be broken if the government takes steps to control at least 10 percent of the country’s annual paddy production.

However, something else has happened. The rice monopoly is now in the hands of a few private mill owners in Sri Lanka, who are closely linked with politics and politicians. As a result, breaking the rice monopoly becomes nearly unthinkable. Mill owners support present political party shifts aimed at gaining or retaining power. These mill owners appear on political platforms too. Recently, some private paddy mill owners, involved in the rice monopoly, were seen aligning with political figures, as reported in the media. Even prior to the elections, these individuals were seen giving priority to protecting their businesses, regardless of which party assumes power. Therefore, despite the grand claims made by presidential candidates about breaking the rice monopoly, now it seems that these promises would remain unfulfilled.

In the past, large-scale paddy mill owners sold rice at Rs 220 per kilogram, based on the government’s guaranteed price. Meanwhile, smaller mill owners sold the same rice for Rs 160-175 per kilogram. This allowed large-scale mill owners to make a profit of Rs 60-75 per kilogram of rice. They earned significant profits from paddy purchased at low prices. Although the government set a guaranteed price of Rs 100 per kilogram of paddy, some large-scale mill owners bought it for as low as Rs 70-80. It is no secret that purchasing hundreds of thousands of kilos of paddy at low prices and storing it led to massive profits. The owners of the several mills sold rice produced from this paddy, bought at lower prices, at much higher prices. According to data from the National Institute of Post Harvest Management, a large-scale mill owner earns at least Rs 4 million in profit per day, which amounts to Rs 120 million per month.

The government must intervene and establish a programme to provide rice to the public at a subsidised price. During the pre-election campaigns it was unfortunate that none of the major presidential candidates had addressed this issue. Just like how some ride the coattails of others’ actions, large-scale mill owners profit no matter whether there is rain, floods, droughts, or elections. Both rice farmers and consumers in this country are left powerless by this situation.