Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The Eastern Province is home to as many as 60,000 war widows who have been forced to become breadwinners of their families upon the death or disappearance of their husbands. 10 years after the war, some are still destitute, going from place to place doing odd jobs as they were not educated or skilled enough to take up ‘dignified’ jobs. Some recall how they last saw their husbands and children many years ago, while others have hopes that they would return one day, thereby making it a challenge for them to get over their emotional and mental turmoil as yet. With such optimism, they are ready to grab any opportunity to voice out their issues, show any written documents they have, to prove that their loved ones are no more and that their requests deserve an answer. This was evident when we visited some of them during a recent visit to Batticaloa.

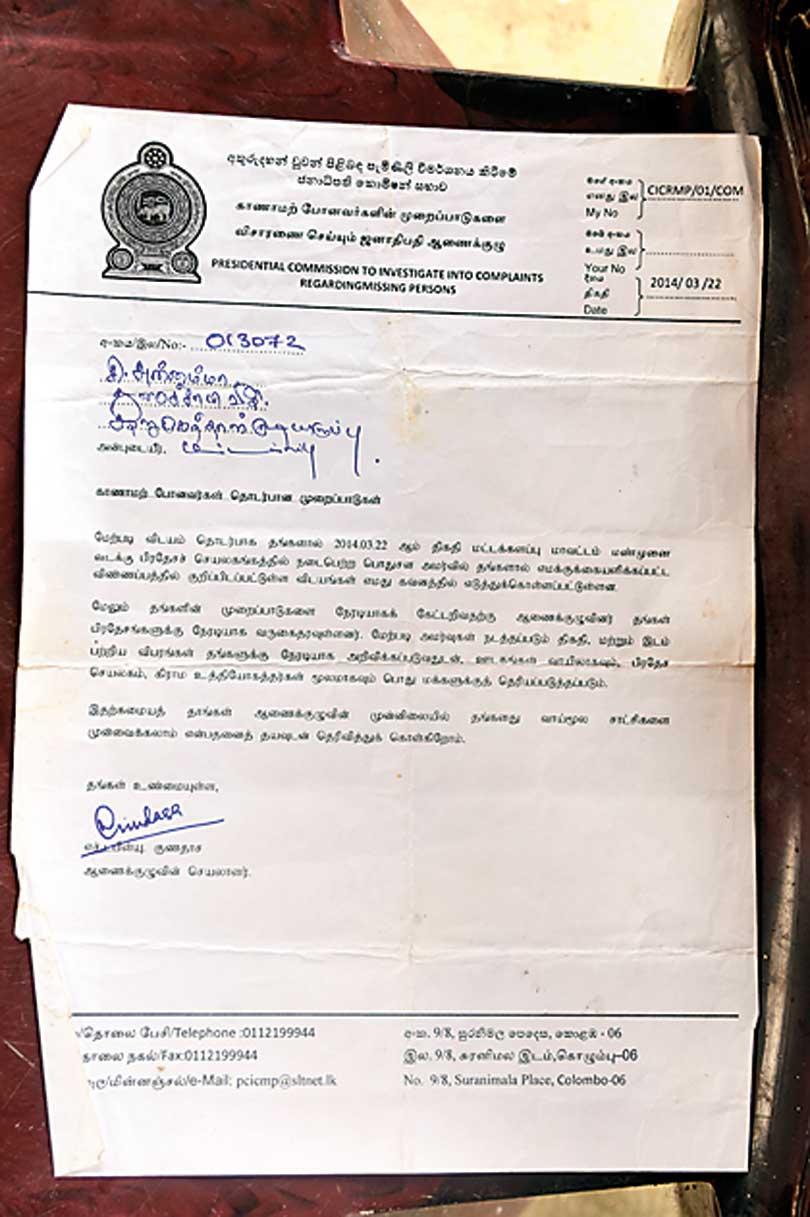

The Eastern Province is home to as many as 60,000 war widows who have been forced to become breadwinners of their families upon the death or disappearance of their husbands. 10 years after the war, some are still destitute, going from place to place doing odd jobs as they were not educated or skilled enough to take up ‘dignified’ jobs. Some recall how they last saw their husbands and children many years ago, while others have hopes that they would return one day, thereby making it a challenge for them to get over their emotional and mental turmoil as yet. With such optimism, they are ready to grab any opportunity to voice out their issues, show any written documents they have, to prove that their loved ones are no more and that their requests deserve an answer. This was evident when we visited some of them during a recent visit to Batticaloa.

Some Tamil mothers still lament over the disappearances or murders of their children. Memories of their brutally assaulted bodies still haunt them. When we met them, they showed us files full of letters and complaints sent to commissions that haven’t received any response. We also came across women who haven’t been entitled to Samurdhi benefits for the past 23 years and have to live off their husband’s salary. Some were promised houses and all that they had to do was fill a form. Proof of that form is still in their files, but no houses were built. This was how they were ‘used’ during regime changes, elections and various other instances when local politicians needed votes. Apart from that the psychological trauma that they have dealt with is beyond description, as many of them may already be suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Whether anybody really questions about how they are ready to accept this trauma remains a question. The Daily Mirror also learned that although there are widows’ societies in the region, they don’t necessarily help those in need. They would charge membership dues from every member, but not do anything in return to help them stand on their feet. Although successive Governments have briefly touched on reconciliation, quite sadly, none of these projects were a success. From public hearings to questioning the accused, profiling the disappeared persons, keeping records and following things up is a cycle that needs to be established. Apart from that, setting up regional branches of these offices and ensuring that they are equipped with qualified officials too is a task vested upon the Government. For how long they would have to wait for justice to be served remains a question and even if they do, compensation and responses to long awaited queries would not bring their loved ones back to life.

When Sinnathurai Annamma was diagnosed with asthma, she had to stop her cashew and peanut supply business. “My son was 15 years old at the time he went missing back in 1997. My other son was injured during a bomb attack. We wrote to many commissions, but didn’t receive compensation. I was only asked to fill a form as proof that my husband passed away. Although I submitted it, I haven’t received any response as yet,” said Annamma.

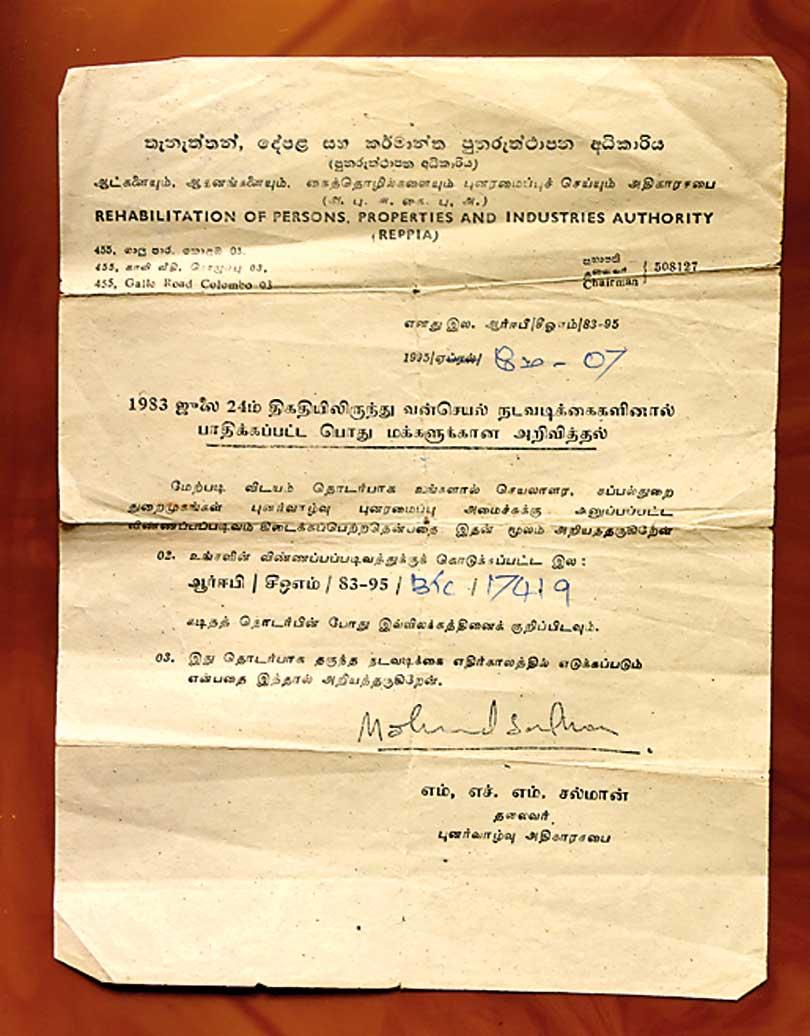

Thiyagaraja Leelavathi’s husband was brutally assaulted by the Army. “The incident took pace back in 1990 where he was taken away on suspicions that he was supporting the Liberation Tigers. Fortunately he didn’t die, but two years later he left us. I’m a housewife and do contract work for a living. We were displaced from our ancestral homes and then resided in Batticaloa after the unrest. We didn’t receive any compensation and 10 years after the war I still don’t have a permanent job. I live with my daughter who has also gone through a divorce and is now working at a non-governmental organisation,” said Leelavathi.

She showed us numerous letters she had written and sent during the past 29 years to places including the Rehabilitation of Persons and the Properties and Industries Authority. But 29 years later, she is still awaiting answers.

We then visited Sellathurai Iswari’s house which was another female-headed household in the heart of Batticaloa. “15 years ago my husband went to work and never returned. After a few days his body was recovered with gunshot wounds. After his demise I started doing contract work and cooking food and giving to the fishermen who work close by. But I would get an income only if they went to sea and found a catch. If they find fish worth Rs. 500, I would get Rs. 200. Sometimes I go to ‘clean’ houses since I don’t have a permanent job. Usually we need around Rs. 30,000 for a month. So far we haven’t received anything from the Government, not even compensation for my husband’s state-sponsored murder,” said Iswari.

J. S Poomani’s son was taken away by the Armed forces when he was in the 10th grade. “We then stayed in temporary shelters for around three years. By the time we returned to our houses they were burgled, demolished or burnt. They asked us to fill a form and promised to give us houses. But we got nothing,” she said with tears swelling up in her eyes. “I live in my son-in-law’s house. My mode of income is by selling different green leaves at shops. Now I don’t have a permanent job and that’s the biggest challenge I face,” said Poomani.

She also opined that widows’ societies don’t help those in need. “We pay membership fees, but they don’t even know if we exist. But if one of us dies they would come and sponsor our funeral and have a funeral ceremony in a grand way,” she said.

Velupillai Kanmani had witnessed how 150 people seeking refuge at the Eastern University were taken away for questioning by the Armed forces. “My 18-year-old son was one of them. This happened in September 1990 and it has been 29 years since I last saw him. After that we lodged complaints at Human Rights Commission, Sri Lanka Red Cross and many other places, but our queries were never answered. We met with those officials as well and we even wrote letters to the Government, but nobody took any notice. 15 years ago I received Rs. 15,000 as compensation, but nothing afterwards. We don’t have any written evidence to prove it. Back then we had a border issue and Tamils and Muslims were fighting over it. We suspect whether the Muslims tipped off the Armed forces to take away our children claiming that they were supporting the Tigers. Thereafter they took away families and chopped them to death,” recalled Kanmani.

Kanmani earns a living by doing contract work. “I cook at the University canteen and sometimes go to clean houses too. I live off Rs. 200-500 that I earn a day. We get Rs. 1300 per month as Samurdhi,” she added.

“My youngest son had to join the Liberation Tigers since there was a period when Tamil youth were taken away by force,” recalled Ganesh Yogeshwari. “He was a member for around three years and later got settled. On the day he was going to open a retail shop his brutally tortured body was discovered. After that we didn’t want to open the shop. My husband is a fisherman and that’s our only income, but during this time of the year it’s off season. The family received Rs. 50,000 as compensation and that was it. I haven’t received Samurdhi after I returned from working overseas in 1997. I used to get Rs. 150, but I don’t get anything now. My husband doesn’t have his own boat. So he has to hire one and that’s quite costly. He doesn’t even have his own equipment,” said Yogeshwari.