Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

DWC officers treating an elephant that suffered gunshot injuries Image Courtesy DWC

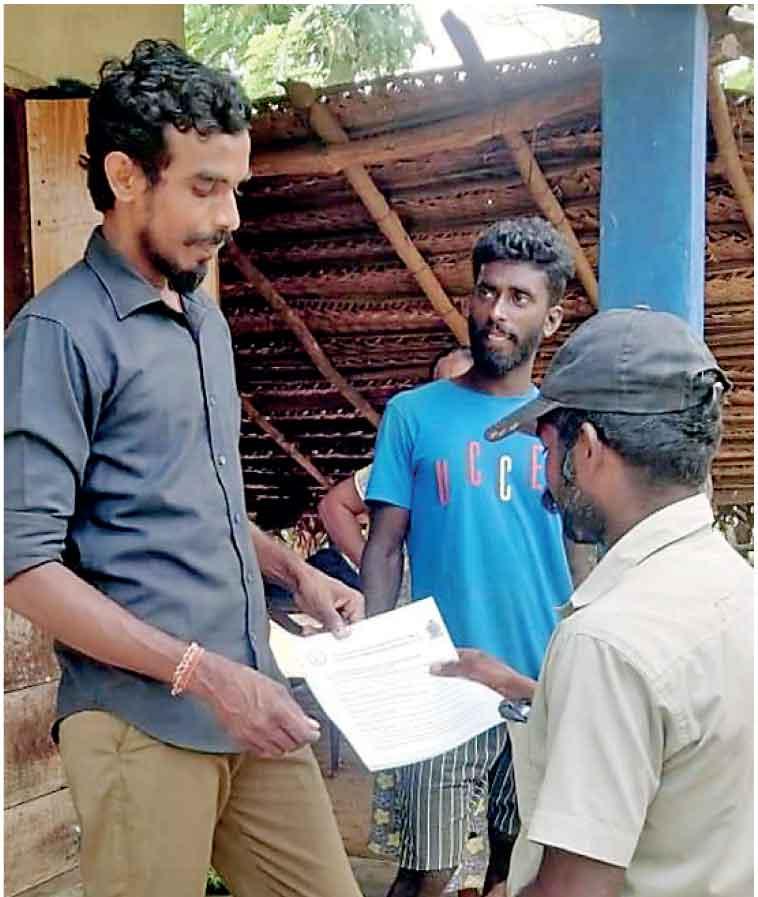

Wildlife officials educating people on electric fences in Kudumbimalai Image courtesy DWC

Elephant carcass found in Giribawa, Kurunegala

“We are also experimenting with a collar system, again working with the ETH of the DWC, to understand if we can use this collar to provide an early warning system to mitigate conflict between villagers/farmers and elephants

The discovery of an elephant carcass in Giribawa on February 6 raised the total count of elephant deaths to 21 for this year. In 2023, Sri Lanka made history as the country with the highest number of elephant deaths, hitting a record high of 400 or more. Elephants are frequently at the receiving end of the ever-aggravating human-elephant conflict (HEC) that was created more than 50-60 years ago, when people moved into elephant territory sans any assessment. As a result, people are more worried about their paddy lands and vegetable plots, and would go to any extent to keep the elephants away. But what they fail to understand is that they have constructed their houses along elephant corridors or near forest reserves which are home to elephants.

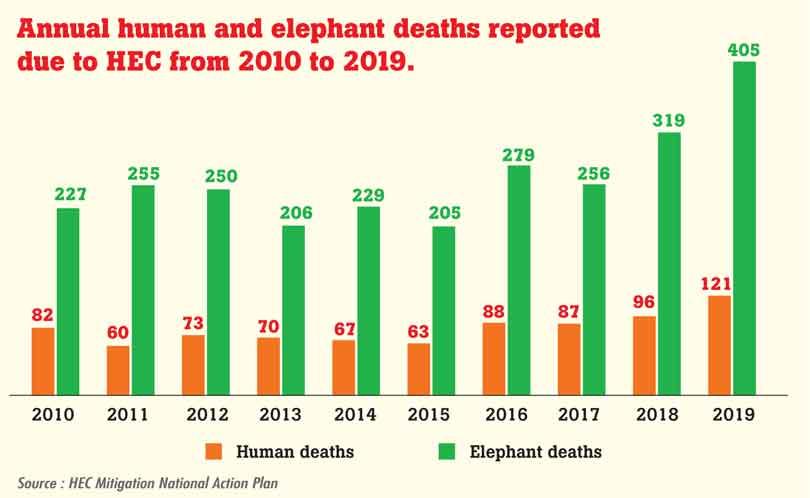

The discovery of an elephant carcass in Giribawa on February 6 raised the total count of elephant deaths to 21 for this year. In 2023, Sri Lanka made history as the country with the highest number of elephant deaths, hitting a record high of 400 or more. Elephants are frequently at the receiving end of the ever-aggravating human-elephant conflict (HEC) that was created more than 50-60 years ago, when people moved into elephant territory sans any assessment. As a result, people are more worried about their paddy lands and vegetable plots, and would go to any extent to keep the elephants away. But what they fail to understand is that they have constructed their houses along elephant corridors or near forest reserves which are home to elephants.

HEC in the North Central Province

The North Central Province is one of the worst-affected areas by the HEC. Most elephants succumb to gunshot injuries while some elephants are subject to illegal electrocution. Others collide with speeding trains. In September last year, within a span of 36 hours, eleven elephants succumbed to injuries as a result of elephant-train collisions. But no practical solution has been implemented to mitigate this situation.

Haphazard encroachment activities have kept people and elephants at war. The HEC has claimed the lives of at least 176 people in 2023. As more humans are being killed, people fear to coexist with elephants. A common notion is that elephant fences and other solutions may not work anymore. “There have to be orders given from above for the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) to provide a lasting solution for the HEC,” opined R. M. J Bandara, a resident from Galgamuwa. Bandara has been working at the grassroots level, raising awareness on the HEC for many years.

He observes how illegal constructions along elephant corridors, environmentally sensitive areas and forest reserves have pushed more elephant herds to raid villages and cause irreversible damages to property and vegetation. “Elephants travel long distances in search of water and food. We have seen how elephant herds in Palukadawala Lake reserve now frequent smaller lakes such as the Ambakola Wewa when water levels in bigger lakes go down. They travel to the Kala Wewa via the Kahalla-Pallekele forest reserve towards the Inginimitiya Wewa, Thabbowa all the way up to Wilpattu. Hence when their usual migratory path has been disturbed they will seek alternatives,” Bandara added.

Efforts by WNPS to Mitigate HEC

As a leading conservation organization in the country, the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society believes that no single mitigative method will solve the problem of the Human Elephant Conflict. “All stakeholders must gather and work in unison to reduce the stress levels of both the farmer and the elephant,” WNPS President, Jehan CanagaRetna. “A mind-set change of how the farmer sees the elephant, and if we can change their minds to make an earning from the elephant will solve a lot of our HEC issues in the future.”

The WNPS experimented on a Light Repel System (LRS) for the past three years which has yielded satisfactory results in 6 districts, at 24 locations. “Currently, we have an 82% efficacy rate for the LRS. We are in the process of compiling a ‘white paper’ so that we can publish the results, and pass on the concept to the government as another effective tool for conflict mitigation.”

The WNPS has supported the Presidential Committee headed by former Director General of Wildlife Conservation, Dr. Sumith Pilapitiya, to monitor the progress of the implementation of the National Action Plan for the Mitigation of the Human-Elephant Conflict, by implementing pilot projects in erecting protective fencing around villages, as well as agricultural cultivations. This is a concept of Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando who has been experimenting with it in two Districts with more than 500 farmers benefiting from it. The idea is to fence the village in and keep the jungle free for the elephants to roam their traditional ranges.

The WNPS is also working on legal proceedings that bring about landmark judgements against perpetrators of elephant killings. “For good reason, we cannot publicly outline the details. We are also working on a method of engaging with villagers, trying to implore them to see the elephant in a different light, with the priority of making them understand that humans and elephants can co-exist. We are trying this out in the Anuradhapura District, and we hope to publish our results within 2 years. We have individuals who are on WNPS pay roll that live in hamlets, and are going through the problem with the villagers, to come up with the best solution. There is no better way than experiencing the stress by living with farmers and understanding the situation first hand,” CanagaRetna added.

Work continues with farmer communities to provide them with immediate assistance to make their lives less stressful, and thereby make the elephants’ lives less stressful too.

In collaboration with the Elephant Transit Home (ETH) of the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) and the Ragama Campus of the University of Kelaniya, the team has conducted research on an antibiotic study to understand the resistance levels of elephants in the wild, in captivity and elephants in the wild who feed on garbage dumps.

“We are also experimenting with a collar system, again working with the ETH of the DWC, to understand if we can use this collar to provide an early warning system to mitigate conflict between villagers/farmers and elephants. This experiment is currently taking place but it will not be until the end of 2024 before we can assess how successful it has been,” he said in conclusion.

Will The Numbers Come Down?

In December 2023, the Sectoral Oversight Committee on Environment, Natural Resources and Sustainable Development presented the National Action Plan for reducing Human-Elephant Conflicts. The committee was chaired by Senior Elephant Researcher, Dr. Sumith Pilapitiya. In their presentation, the Committee pointed out that wild elephants have spread across 62% of the country’s landscape and that the construction of community-led electric fences is the most viable solution to minimize the HEC.

But even though electric fences seem to be the most viable solution, many elephants succumb to illegal electrocution. As a result, DWC officials are now conducting a survey to ensure that private electric fences have direct current instead of alternating current. “We don’t have adequate technical staff but we are now working in different zones to educate people on constructing standard electric fences,” said DWC Director General, M. G. C Sooriyabandara. “The DWC has put up electric fences in certain areas, and people should ideally take these fences as an example.”

When asked about the rise in elephant-train collisions, Sooriyabandara said that there doesn’t seem to be any increase, but several elephants succumbed to injuries within a span of a few days in 2023. “We found that these incidents are likely to occur in places where new railway tracks have been laid or when trains run behind schedule. We have deployed our officials to clear the thick shrub growing on either side of railway tracks to minimize elephant-train collisions.”

Sooriyabandara further said that a collaborative approach among stakeholder institutions would help provide more feasible solutions to minimize HEC. “Already the Department of Agrarian Development has started putting up fences around plots of agriculture in areas with a heavy HEC. The Railway Department is working on a plan to minimize accidents. This way going forward we hope to bring down the number of elephants as well as human deaths.”