Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Male and Female in Yala Buffer

The Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya) – IUCN Status: Vulnerable. Estimated range loss (2016): 63%

We are the IUCN Red List assessors for the Sri Lankan leopard having been members of the IUCN’s Cat Specialist group since 2002

It may be a dubious feat to celebrate, but the Sri Lankan leopard has the lowest overall loss of historic range of all the sub-species, with ~37% of its previous range remaining.

This is perhaps a testament to the conservation ethic that can be found here, underpinned by religions which foster the notion of shared space and the metaphysical overlap of humans and animals. Despite many naysayers insisting that little is known about the leopard in Sri Lanka, it was clear at the GLC that this island’s population is, in fact, one of the better researched of all sub-species, with a solid understanding of the distribution and numerous habitat-specific estimates of numbers and behaviour.

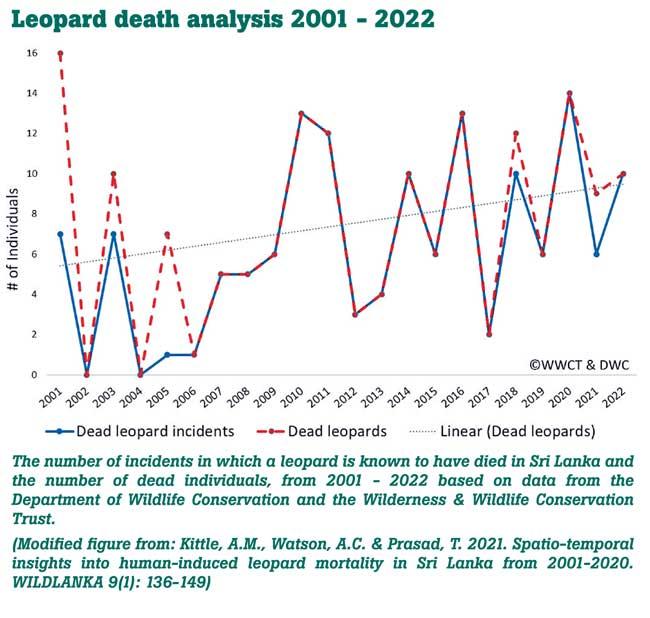

We are the IUCN Red List assessors for the Sri Lankan leopard having been members of the IUCN’s Cat Specialist group since 2002. Using all of the data that has been published on the Sri Lankan leopard as well as additional unpublished data from our long-term research, we estimate that 550 – 1050 adult leopards live in Sri Lanka with the population reasonably stable in the decade from 2008 – 2018 (estimated population reduction of ~7%). This relative stability led to a down-listing of the sub-species from Endangered (higher risk) to Vulnerable (lower risk but still a threatened sub-species). A fast-track re-assessment has been requested to ensure that rapid land use changes are accounted for in this sub-species assessment.

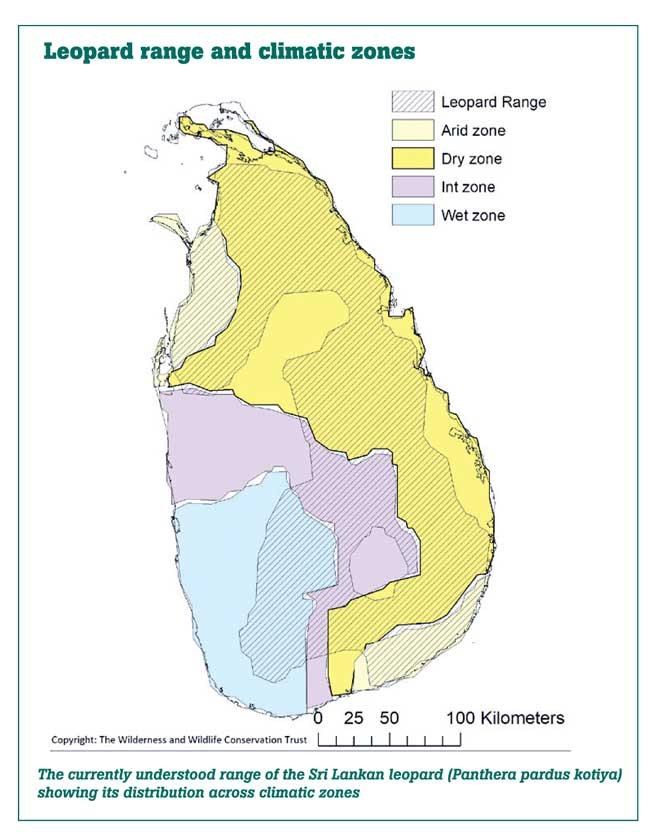

The positive news is that the leopard is still found in all habitat types in Sri Lanka from the arid coastal scrub of Yala, to the extensive lowland dry zones characterized by Wilpattu NP, Wasgamuwa NP and others. The transitional intermediate zone is also home to leopards, exemplified by Victoria-Randenigala and the area west of Gal Oya. The lowland wet zone, excluding the heavily urbanized coastal section, remains home to leopards, as documented at Sinharaja down to Deniyaya, while the sub-montane wet zone – mostly unprotected tea estate lands – also harbour relatively stable populations.

The montane zone forests of Horton Plains NP are so suitable for leopards that they are fast becoming the park’s star attraction! The negative news is that the leopard range continues to contract as human infrastructure expands, particularly post-civil war. In addition, retribution killings of leopards driven by livestock depredation (typically calves and goats) are not uncommon – particularly in the lowland dry zone - but the extent of leopard mortality from this scenario is not yet known. The inadvertent killing of leopards which get caught in wire snares typically set for wild boar and/or deer, is a serious issue in the Central Highlands certainly, and possibly other areas as well.

Thankfully, Sri Lanka is replete with citizens who care a great deal for the future of the leopard in the country, so various individuals and organizations (including ours), are making concerted efforts to combat some of these threats. For our part, WWCT has been conducting ecological and behavioural research on the Sri Lankan leopard for over 20 years, building on the research done by earlier generations and gathering a lot of key baseline data that has led to the improvement of our understanding of leopard distribution and abundance.

Thankfully now, the next generation of researchers is starting to emerge so hopefully the future monitoring of the species will continue to improve. In an all-too-familiar pattern well known to wildlife researchers, our research direction has changed substantially over the years, from baseline ecology to conservation as the realization becomes impossible to ignore that the long-term future of the species needs dedicated interventions on the ground. Most of our current research is conducted in unprotected landscapes as we have realized that these areas form the essential links between the more secure, protected areas and are vital for leopard dispersal and population connection. That the Sri Lankan leopard population does not become a series of unconnected, isolated sub-populations is essential for it to remain viable in the long term.

The next set of articles will delve into the ongoing work with the Sri Lankan leopard.

Copyright Kittle & Watson, WWCT.org (2023), Wilderness & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Sri Lanka. All work by WWCT is conducted under the purview of and often in collaboration with the Department of Wildlife Conservation, Sri Lanka. This article is Part IV in a series of articles by WWCT on leopard conservation.