Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A study led by a young Sri Lankan marine biologist tells us that over 90% of small fish found in samples from Negombo, Kudawella and Trincomalee contain microplastics. In other words, if your diet includes small fish, you’re most likely ingesting plastic as well.

Fish is widely considered as one of the healthiest foods, vital for wellness. It is rich in nutrients such as protein, vitamin D and Omega-3 fatty acids, important elements of a healthy diet. Yet, research from around the world now suggests that the fish in your diet, most probably contain small but significant amounts of plastics.

24-year-old Vinuri Silva, a marine biologist, in the course of conducting research for her honours year at university, has found this alarming news to be true for the small fish species of Sri Lanka as well. With over 8,000 square miles of territorial waters surrounding the island and a population which regularly consumes fish as a part of its staple diet, Vinuri, however, is surprised that there is no previous research to be found on this subject.

A past pupil of Visakha Vidyalaya and Gateway College and the daughter of Army Commander Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva, Vinuri has always been drawn to the deep waters. “I was always interested in sports such as rowing and swimming. Nothing on land, it had to be in the water,” she recalled. When Vinuri moved to Adelaide, where she would pursue her higher studies, she had no idea she would stumble upon marine biology as a career. “Despite my love for water, I didn’t really know about marine biology when I was in Sri Lanka. It wasn’t a known career to consider here. But I did like science and when I saw that I had the option to study marine biology when I was enrolling in university, something clicked,” she said.

When I was thinking about research topics for my honours year, I happened to attend this random meeting about garbage at a local authority in Adelaide

Her marine biology degree at the University of Adelaide required three years of study, following which she had to decide on a research topic for her honours year. In her pursuit of a supervisor for her research, Vinuri found Prof. Bronwyn Gillanders, a renowned Australian marine scientist whose research spans freshwater, estuarine and marine waters, who was willing to support her.

“I’ve always wanted to do something for my country. Asha De Vos is doing great work with whales and ocean education. But Sri Lanka is an island nation which has got so much to offer and I’m surprised that the study of marine biology is not a bigger option here,” she shared. Driving her point further, Vinuri added that she was the only student studying marine biology from Sri Lanka at her university.

“When I was thinking about research topics for my honours year, I happened to attend this random meeting about garbage at a local authority in Adelaide. They spoke of garbage management and a presentation highlighted how garbage was disposed. At one point they presented a graph that showed the top ten countries which were polluting the oceans the most. To my surprise, Sri Lanka was the fifth largest contributor of plastic pollutants,” Vinuri said.

“On my way back from this meeting, I asked many of my friends if they knew that Sri Lanka was the fifth top polluter of oceans, and nobody knew. Then I called my friends and said, ‘I think I know what I’ll do for my research project.’”

Her research supervisor Prof. Gillanders was soon on-board with Vinuri’s idea, as she was already conducting similar research in Australia. “Prof. Gillanders was very keen to see the difference between the two countries. Garbage disposal and waste management is very different in Australia and Sri Lanka, so that aspect was interesting to research too,” Vinuri said.

Fish for thought

The microplastic particle content in fish is a relatively untouched topic in Sri Lanka, according to Vinuri. “My supervisor gave me the freedom to pick the species and the area. We decided to select smaller species, not only because it’s easier to transport but also because they are consumed whole. I picked three varieties; sprat, herring and sardinella. (haalmassa, hurulla and saalaya) They’re also supposed to be very nutritious as well,” she said adding that their wide consumption was another reason for the selection.

I asked many of my friends if they knew that Sri Lanka was the top fifth polluter of oceans, and nobody knew. Then I called my friends and said, ‘I think I know what I’ll do for my research project

Early in 2019, just over 150 fish from Trincomalee, Kudawella and Negombo were collected. Vinuri exported the fish to Australia with the help of the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA).

“What I looked for in my research is microplastics, which are small pieces of plastic less than 5 millimetres,” Vinuri explained. Her supervisor then suggested that they look for the same species in Australia to obtain a direct comparison. “I found two of the same species, but I couldn’t find Saalaya.”

The results were alarming and confirming the overwhelming research worldwide. “Almost 40 to 55 per cent of the fish I looked at from Australia had microplastics in them, whereas from the fish I took from Sri Lanka, over 90 per cent had microplastics,”

she revealed.

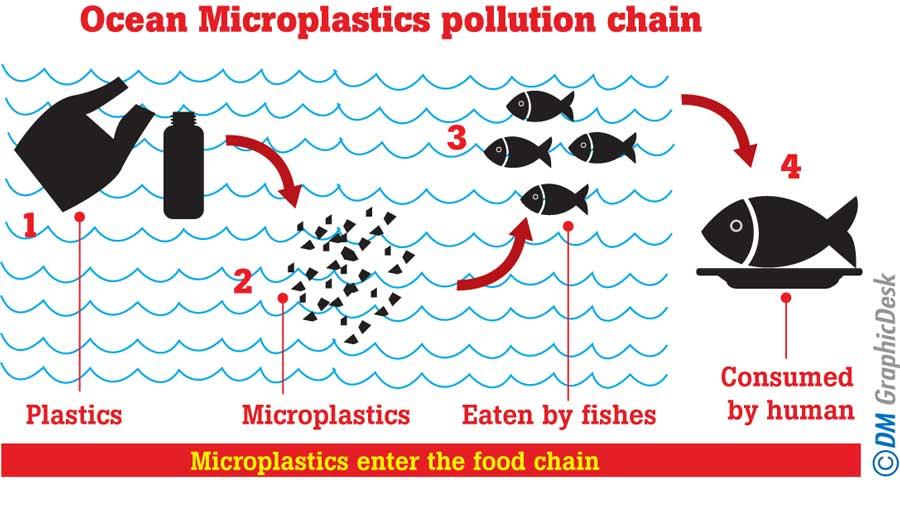

“These are small fish, so you can imagine how it gathers up in the food chain. What I found interesting was that we eat them as a whole, so whatever’s in these fish is potentially going into our systems as well. Unfortunately the human health aspect of it, I don’t have the knowledge to explore. There is a huge research gap there,” the young marine biologist highlighted. Given the opportunity, Vinuri is eager to partner with research efforts to help bridge this gap. She also intends to do similar research on the content of microplastics in dried fish (karawala) and publish her findings in a scientific journal.

Bridging the gap

Vinuri is set to commence studies for her PhD in April, which she estimates will take the next three to four years of her time to complete. “Most science students pursuing research interests in a foreign country are not allowed to study something related to their home country. In that aspect, I was quite fortunate to be able to do something relevant to Sri Lanka, because I had a very supportive supervisor. I haven’t selected an area of study for my PhD yet, but I’m hoping to relate it to Sri Lanka as much as I can,” she beamed.

She adds that she is doubtful of pursuing a career, after all, she is still 24 years old. Vinuri recollected that she was contacted on social media by a young girl who wished to study marine biology recently. “I’m happy that marine biology is slowly being recognised as a career option here. This country has a lot of potential in terms of its marine life and beaches, but I don’t know if there are people who are knowledgeable enough to contribute to its betterment,” she commented.

During a recent visit to the coast, Vinuri had observed how the Sri Lankan Navy is attempting to revive the declining coral reefs of Sri Lanka. “I’ve seen for myself that this project is working out really well. But imagine if there were more scientists working with the Navy, there would have been a lot more that we could do, especially in terms of conservation,” she wondered.

Asked of her potential interests of study, Vinuri said that she hopes that Sri Lanka’s plastic issue can be resolved. “I know it’s a big ask. But if we can get out of the top ocean polluters list or at least come down in the rankings and figure out the answers to this problem, it will be a huge achievement. Sri Lanka is such a small country to be in the top five,” she added.

According to a United Nations report in 2017, 51 trillion microplastic particles --500 times more than stars in our galaxy – litter the seas. Each year, more than eight million metric tonnes of plastic end up in oceans, the report said. According to estimates, by 2050, oceans will have more plastic than fish if present trends are not arrested. This young scientist too is worried about the alarming plastic consumption in Sri Lanka.

“We don’t have substitutes for plastics, which is a real problem in Sri Lanka. When plastics are dumped in the ocean, they take longer to break down, because there’s less exposure to UV light,” she explained. Vinuri stressed that in Sri Lanka there are no regulations, especially when it comes to marine life and ecosystems. “My goal is to get people to change their mentality and really understand the depth of this issue. It’s a cycle when we dispose of plastics, they reach the ocean, it breaks down into smaller pieces, which will get eaten by fish and eventually end ingested by humans. I want to help people understand this and change the way they see plastic usage,” Vinuri stressed.