Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

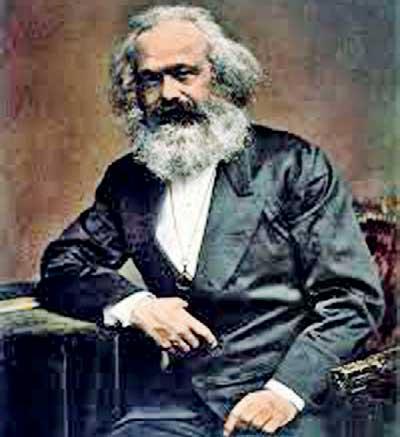

Karl Marx did something no other economist or thinker before him had: he reduced everything, if not almost everything, to the level of relations of productions. History, he wrote, was a process that repeated and returned to itself. In 19th century Europe this idea of an historic recurrence led to either of two extremes: to an embracement  of the status quo (the path Hegel followed) or to a wholesale repudiation of it (the path Marx followed). By bringing the cultural, social, and personal to the economic, Marx restored, if not wedded, the economic to the political.

of the status quo (the path Hegel followed) or to a wholesale repudiation of it (the path Marx followed). By bringing the cultural, social, and personal to the economic, Marx restored, if not wedded, the economic to the political.

Today when I see artistes, professionals, and intellectuals calling for a new political order devoid of political representatives, I tend to get bewildered. The divorcement of the non-political from the political was rendered meaningless the moment the world entered the 17th century, and ever since Louis XIV pompously declared, “L’état, c’est moi.” What the West bequeathed to the world – and this remains the most significant contribution by it thus far – was the State: secular, at least in a cosmetic form, and based on a tradition of continuity. Even in its most archaic, minus a popular mandate but with a mandate of heaven, it was rooted in some form of representation.

At a protest rally organised soon after Mahinda Rajapaksa was illegally sworn in as Prime Minister, there were professionals who gloated that they would not pay taxes if the parliament elected to represent him was made up of drug peddlers. The “I-won’t-pay-taxes” threat, a rehash of “no taxation without representation” slogan, is a middle class cosmetic which few people in the lower classes can or will be able to brandish: less than 10% of our GDP comes from taxation, not much considering that the figure in the seventies was around 20% and the OECD average is 34%. The bulk of these taxes are not direct but indirect; they hit at the lower class. I did not see any member of that lower class at that rally.

The failure of the right-wing and left-wing intelligentsia in this country has been their refusal to spot out, and infer, the economic (or political-economic) aspect to an issue. In this the left-wing intelligentsia has to share the bulk of the blame, because unlike their counterparts and colleagues to the right, have at least their Marxist legacy which should theoretically have enabled them to avoid this ideological fallacy. When calls made against hate speech and for individual rights are made without as much as a passing reference to the social inequalities underlying the issues giving rise to their protests, the intelligentsia, whatever their orientation, is thus doing itself and the country a disservice. This is not an illusion we can hold on to for long.

"No one is going to get at a national consensus until we strip these social and cultural problems"

Western political philosophy reached its apogee with the triumph of capitalism and private property in the late 17th century. Thomas Hobbes presented a Hobson’s choice for the citizen: freedom without stability, or stability with limited freedoms. In 2015 we were faced with roughly the same choice: as Dr. Dayan Jayatilleka put it, “change without continuity” (Sirisena) or “continuity without change” (Rajapaksa).

Like Machiavelli, who’s got a bad press over his attempts at justifying the unification of Italy, Hobbs was pandering to the political climate of his time. With every era thereafter, from Hume to Locke to Montesquieu to Rousseau, Western philosophy wremained attached to the zeitgeist of that climate: the need for reform favouring a nascent and maturing capitalist bourgeoisie.

The argument was that man had fallen from grace: he was living in a state of nature. In Hobbs’s formulation, this state of nature was “nasty, brutish, and short”, whereas in Locke’s formulation it was a paradise that antedated the need for property (man lacked the will to divide property; the State was needed to preserve the right to it). Either way, it heralded the rise of a propertied political order, which later came to be known as liberal democracy – the sort that the left and right here repeatedly call for.

The United States Declaration of Independence did not recognise a right to happiness merely a right to pursue happiness. This new “capitalist order” (as Fernand Braudel described it), rational and fascinated with the idea of maximising gain and minimising loss (the idea of utility), is the essence of the State today. The left’s call for an overhaul of the political order we have here is hence pointless, because no amount of constitutional amendments are going to change the oppressive nature of that system. But our intelligentsia remain attached to campaigns that have brought off the ultimate deception: a movement that talks big on social ills without mentioning the economic foundation to them.

"Since 2015, we have seen one oppressive economic measure after another being piled on the people"

No one is going to get at a national consensus until we strip these social and cultural problems of the frill that gets added to them by ideologues and get at their essential character. The fact that we have not been able to do this, however, is in large part due to both sides of the spectrum: the rights brigade for demanding a halt to displays of populist nationalism without getting to the roots of populist nationalism, and the petit bourgeois nationalists for demanding a halt to manifestations of minority grievances without getting to the roots of those grievances.

Politicians who take to Twitter claiming to speak for true Buddhists and urging everyone to take a stand against chauvinists, without considering the economic policies that put an inexorable strain on the lower (middle) class and fuelled chauvinism, are hence engaging in doublespeak.

Since 2015, we have seen one oppressive economic measure after another being piled on the people. We have seen price hikes; attempts at privatisation, deregulation, and scaling down of State property; simmering ethnic tensions made worse by statements by ministers who went mum when tensions flared up in other communities; proposals to recognise a Joint Opposition that stood apart from a government and a government-appointed Opposition shelved off, causing the JO to seek popular support outside the parliament; and activists and intellectuals whose mouths never open over, and against, the government’s less than stellar economic policies.

Since 2015, we have seen one oppressive economic measure after another being piled on the people. We have seen price hikes; attempts at privatisation, deregulation, and scaling down of State property; simmering ethnic tensions made worse by statements by ministers who went mum when tensions flared up in other communities; proposals to recognise a Joint Opposition that stood apart from a government and a government-appointed Opposition shelved off, causing the JO to seek popular support outside the parliament; and activists and intellectuals whose mouths never open over, and against, the government’s less than stellar economic policies.

The short-lived Rajapaksa-Sirisena administration, as one writer pointed out aptly in an article in Jacobin magazine (“The Crisis in Sri Lanka”), was a “remarkably peaceful affair” greeted by “near silence.” Indeed, hidden beneath the protests and the demonstrations, the “I-am-not-here-for-Ranil-but-for-democracy” slogans and slogan-bearers, was a simmering hatred of the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe regime.

If the Rajapaksa administration achieved one small thing in their three months in power, it is this: it eroded any popular sympathy for the neo-liberal wing of the UNP. This process of declining credibility accelerated after the Easter bombings.

You can call the Rajapaksas fundamentalists, chauvinists, populists, and demagogues. You can argue they and the rest of their brigade are motivated by a megalomania which remains unprecedented in our history. You can make the case for the belief that the country is suffering because of its political representatives. To me these remain convenient, lazy and reductionist conclusions of a consumerist middle class exculpating itself of guilt over its less-than-considerable contribution to the country.

Politics is inseparable from economics. Economics is inseparable from culture and society. And culture and society are inseparable from us. Attributing the issues of the present to politicians and populists, without giving due weight to those who provoked those issues through malignant economic policies, is avoiding one dead-end for another. It has not, does not and will not work. If we are aiming at a national consensus, we should thus go back in time, read wMarx, if not the followers of Marx, and strive to wed the political with the economic.