Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Moses Saman is a Spanish-American (born Peruvian) photojournalist who specializes in the coverage of war and civil conflict. An article about him published in the Guardian UK (written by Tim Adams) showcases his coverage of the post-conflict situation in northern Sri Lanka.

That made me think of how the nature of war (or conflict) photography has changed over the years, and what makes some photojournalists choose this dangerous sphere of work and how they stand out from the rest.

The term ‘war photographer’ which brings to mind Robert Capa, Dmitri Baltermans or W. Eugene Smith, is no longer in use.

‘Conflict photographer’ isn’t a substitute, but it does bring up an attitude – these are people willing to risk their lives covering not just wars and civil wars but riots, civil unrest, natural disasters and the like. The mortality rate among them remains surprisingly low given the risk levels, but the recorded deaths-Robert Capa in Vietnam, and more recently Remy Oshik in Iraq (2012) and Afghan photojournalist Shah Marai killed in Kabul last year – are sobering reminders that these are a special breed of people willing to take repeated risks in high-risk zones.

Among the contemporary photojournalists working in this field are Pete Muller, Joao Silva, Donna Ferrato, Nicole Tung, Robin Hammond, Eros Hoagland and Denis Sinjakov, among others.

This is the younger generation but veterans such as James Nachtwey, who took gruesome images of East Timor in the late 1990s and was later wounded in Iraq, are still working. He’s now 65.

Presently based in New York, Saman has covered conflicts for almost 20 years and has worked for Magnum, the international news photo agency founded by Robert Capa, since 2010. His post-conflict images of northern Sri Lanka are a pointer, however, to how the nature of this risky profession has changed. Rather, the focus has shifted from direct action in combat situations to the aftermath – days, months or even years after. Moises Saman, now 44, visited Sri Lanka last year, a decade after the war ended, and still managed to find the images he was looking for.

It was while covering the war in Iraq that he got personally involved, to the extent of marrying an Iraqi-Kurdish woman. That, he says, “opened up a completely new set of questions for me.”

His photography shifted from the objective to the subjective. His coverage of the Arab spring which began in Tunisia in 2010 led to a book called ‘Discordia.’ As Saman puts it: “Over these years, the many revolutions overlapped in my mind became one blur, one story in itself. In order to tell this story the way I experienced it, I felt the need to transcend a linear journalistic language and instead create a new narrative that combined the multitude of voices, emotions and lasting uncertainty I felt.”

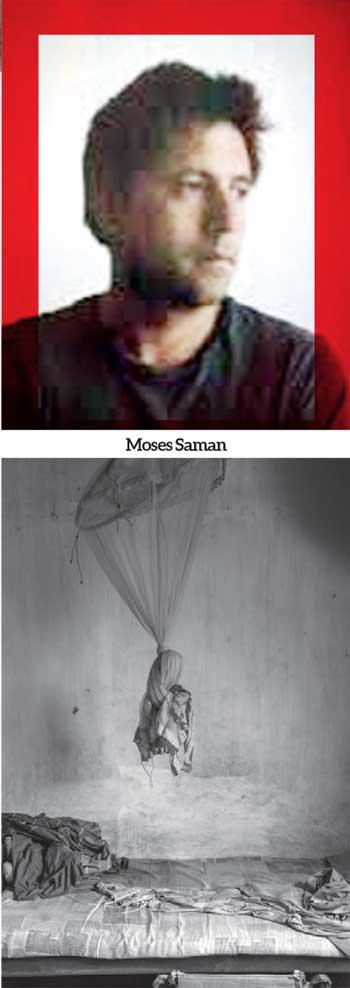

He says that his photographs taken in Sri Lanka represent a recurring theme in his work – how wars leave their mark on people and places long after they end and media focus has shifted elsewhere. The published images – a decrepit room with an empty bed and a mosquito net, a makeshift memorial to civilians slain in the last stages of the war in the shape of a bloodstained hand, the ruins of an outdoor theatre in Point Pedro and a 70-year-old woman from Jaffna whose son disappeared in 1996 – are interesting because, seen strictly from a local point of view, they would be unremarkable. Most Lankan newspapers would not even consider publishing them.

This is not to detract from the quality of Saman’s work. But I have always been struck by the disparity between the two worlds of photojournalism – that of ours, with people working under all kinds of official restraint, and those who work for international agencies. These are the images which get noticed.

I have travelled in the northeastern war areas only twice (to LTTE held areas in Batticaloa and Mannar during the 2004 peace accord on my own and once with the murdered journalist Sivaram) and have taken similar images.

But no one ever found them remarkable or even interesting. This is not an attempt to assess my own work. Rather, it is an attempt to assess those agendas and socio-cultural and political parameters which push us into this localised slot.

The element of self-censorship plays a key role in this. For the visiting correspondent or photojournalist, that doesn’t come into play. His or her survival depends on not censoring in their minds what they see. Another key factor is personal prejudice by someone from this or that ethnic group against another, majority vs. minority and vice versa. The visitor may bring his or her own prejudices, or bias, but that doesn’t lead to self-censorship.

The element of self-censorship plays a key role in this. For the visiting correspondent or photojournalist, that doesn’t come into play. His or her survival depends on not censoring in their minds what they see. Another key factor is personal prejudice by someone from this or that ethnic group against another, majority vs. minority and vice versa. The visitor may bring his or her own prejudices, or bias, but that doesn’t lead to self-censorship.

Personally, I’ve never let either self-censorship or personal prejudice play a part in my assessment of any situation related to ethnic issues and related conflict. But I’ve had to deal with official censorship, as well as self-censorship as is practised by the media.

You can take pictures or write as you please, but that’s for your own benefit if you can’t see it published. Then there is the factor of cultural immunity – a visitor with media accreditation, whether Western, Indian or African, enjoys that whereas we fall victim to broadly assumed cultural prejudices and assumptions, as long as we operate locally, by being what we are – Sinhalese, Tamil, Muslim, Malay, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu or whatever.

"This is the younger generation but veterans such as James Nachtwey, who took gruesome images of East Timor in the late 1990s and was later wounded in Iraq, are still working. He’s now 65."

Each conflict, in any case, has its own logic towards those who try to interpret it. The most fertile ground for news images was Vietnam six to seven decades ago. The world’s most searing pictures came out of that. But the depth of image-making is always subordinate to the politics of a given conflict. Vietnam was a revelation to photojournalists because, at least on the South Vietnamese-American side, restrictions which bound them during WWII and the Korean War no longer existed. The suffering of both soldiers and civilians could be revealed. Even atrocities by the South Vietnamese and American military, if not officially allowed, were captured on film and the American press published such images. The My Lai massacre, reported by an American photojournalist, is a famous example.

In our case, this wasn’t allowed and depicting civilian suffering was limited by censorship and self-censorship to our side. Each side told its own story. During the final days of the war, the government allowed images of soldiers helping Tamil civilians, not the huge suffering caused to them by constant bombardment. Of course one can argue that the Americans were fighting a ‘foreign war’ and we were fighting our own. But then, we were fighting a section of our own people, and it is morally repugnant to ignore their suffering and pretend that it didn’t exist, or that our soldiers were just as capable of atrocities as the Tamil Tigers were.

This is an attempt as to find out why, in so many conflicts across the third world, it’s the international media (agencies such as Magnum) which have captured the most poignant and telling images. It’s more a question of context than talent. Of course, not everyone who works for Magnum, for example, has unblemished records. Some of those paparazzi photographers who chased Princess Diana to her death on that fateful night worked for Magnum and other top news agencies.

It is, therefore, a question of shifting contexts and how one chooses to work, and where. At the end of the day, those who want to see our war from the outside will see it from an outside perspective. The war is over, but there are memories and mementoes, and the problem remains our own.

As Moses Saman puts it succinctly:

“A lot of what went on has been forgotten, certainly in the outside world. When people think of Sri Lanka now, the first thing that comes to mind is probably not the civil war. It is tourism, the beaches. It is really a beautiful place, but there is also this historical memory. While some agencies such as the UN are actively trying to find out what occurred there is little political will. There are still a few trials going on, but the truth is very hard to find.”