Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

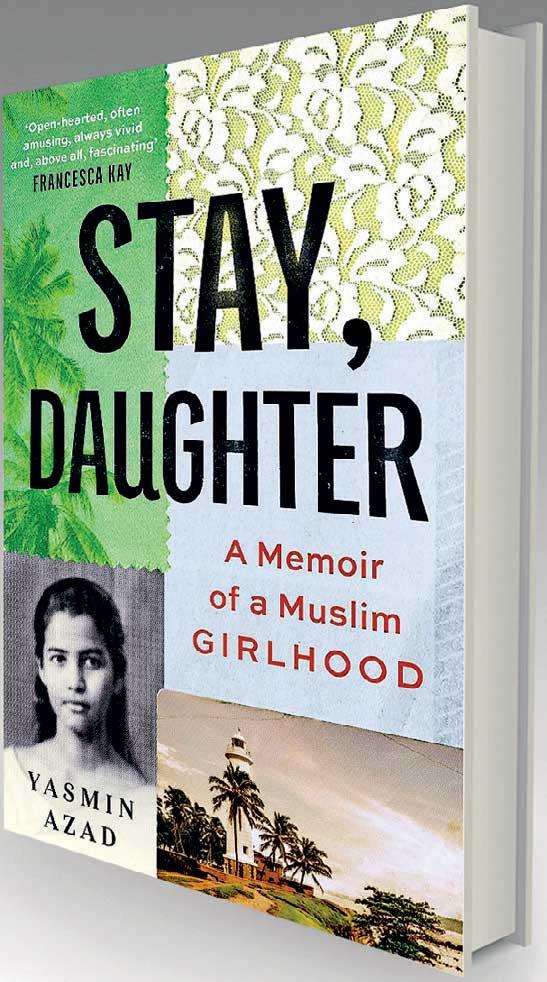

Yasmin Azad’s ‘Stay, Daughter’ is a gem of a memoir, going a long way to dispel the stereotype racial view of Muslims as ‘backward.’

She gives us vivid portraits of the Muslim community in the Galle Fort as well as the entire multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan socio-economic mosaic there

Her cameo portraits of people and places within the fort are superb

In fact, I have never come across such a detailed picture of life in that cramped, enclosed space ‘less than a tenth of a square mile’ – not even in Brohier’s writing, as he was more interested in the architecture than in people

As written earlier in this column, I stopped writing book reviews because my own fiction writing was getting neglected; there wasn’t enough time left to write and edit my own work after reading all those books sent to me for reviewing.

As written earlier in this column, I stopped writing book reviews because my own fiction writing was getting neglected; there wasn’t enough time left to write and edit my own work after reading all those books sent to me for reviewing.

But, after Yasmin Azad sent me a copy of ‘Stay, Daughter,’ a biographical work narrating her childhood in a conservative Muslim community in the 1950s and 60s, I knew I’d be committing a great injustice if I didn’t review this insightful and delightful book. So, this will be that exception which proves the rule.

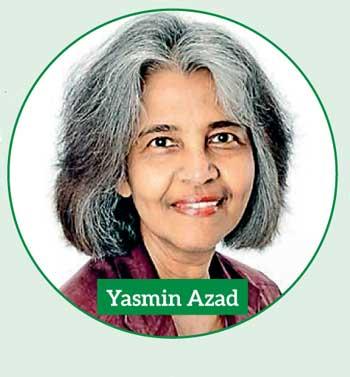

Yasmin Azad, among the first female Muslim graduates in Sri Lanka, migrated to the US and where she worked as a mental health counselor. This is her first book, initially published here in 2020 and this edition published in the UK last year.

I am both delighted and astonished by the quality and elegance of her prose. She writes like a pro, and is able to give us vivid portraits of not just the Muslim community in the Galle Fort, but of the entire multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan socio-economic mosaic there at the time. In fact, I have never come across such a detailed picture of life in that cramped, enclosed space ‘less than a tenth of a square mile’ – not even in Brohier’s writing, as he was more interested in the architecture than in people.

I am both delighted and astonished by the quality and elegance of her prose. She writes like a pro, and is able to give us vivid portraits of not just the Muslim community in the Galle Fort, but of the entire multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan socio-economic mosaic there at the time. In fact, I have never come across such a detailed picture of life in that cramped, enclosed space ‘less than a tenth of a square mile’ – not even in Brohier’s writing, as he was more interested in the architecture than in people.

She was fortunate than most girls in her community – her father, a successful jeweller, loved his family with a broader view of the world than his contemporaries. Her grandfather, a ship’s chandler and more exposed to ‘Parangi ways’ than his friends and relatives, enrolled his daughter in the fort’s English girls’ school – a first for his community. Yasmin’s father not only sent his daughter to school – he allowed her to socialize with Penny, her Dutch Burgher friend, bought her a bicycle, a piano, and even tolerated her being taken to Queen’s cinema, Galle, to see English movies.

His most tolerant act was to overcome all misgivings and giving her permission to attend university.

The author starts her book, characteristically, with these lines: “We did not stay in our homes. Not in the way our grandmothers had, or our mothers. We went out a little more and veiled ourselves a little less.”

Her grandmother doesn’t know how old she is or when she was born – “My grandmother’s life kept rhythm with the moon; she kept track of its waxing and waning. Every four weeks or so, when it seemed about time, she stepped out into the garden and searched the night sky. If she spotted what she was looking for – the faintest of crescents glowing in the dark – she hurried to announce a new month had begun.”

Her cameo portraits of people and places within the fort are superb. There is Majid Nana, the itinerant trader, whose visits are eagerly awaited by women mesmerised by the treasures he brings on a bundle on his head – “the cottons came first: the cambric and flowered chintzes women used for everyday wear, the striped Java sarongs worn by men. Next, lace, both broad and narrow, for trimming blouses and underskirts. And last of all, the saris: delicate voiles, Manipuri silks with intricate cord work, georgettes embroidered in every colour of the rainbow.”

Her descriptions of the cosmopolitan life inside the fort are equally colourful and vivid: “Every Sunday, from the Dutch Presbytarian Kirk on Upper Church street and All Saints’ on Middle, bells pealed and hymns spilled out into the streets. Alongside the harbour, the grand bands of visiting ships regularly played dance music while crowds stood by to listen. The most religious of the Kafirs’ songs came, too, once a year, to people’s very doorsteps. On Christmas Eve, Portuguese carollers dressed in colourful clothes walked the streets and stopped every few yards to sing. While the violins played, the young among spectators intertwined their arms and danced on the streets. Muslim men stood on the verandah and watched while their women peered from behind lattice curtains.”

Learning to dance at Penny’s house, the author began to read American comics – Tarzan, Superman, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse. Old copies cost 50 cents each at the ‘Kalla Thoni’ (illegal immigrant) Tamil man’s small book shop, while she goes on to give us a behind the scenes vista of the enclosed, narrow, back alleys behind Muslim homes: “…a neighbour’s goat wandered over to chew on sprigs of jack leaves…and ducks waddled in to splash in mud puddles left behind by monsoon rains. The smells from adjoining kitchens mingled and wafted in the breeze….”

An almost impish sense of humour runs through the book. When Penny’s parents take the author along to watch the film version of Swan Lake, the audience is shocked by male dancers in skin suits with bulging groins, and spectators start leaving, exclaiming: “Aiyo, what kind of indecency is this? (Vili lajjaavak!).”

The only film her mother ever wanted to see was ‘The Ten Commandments’, while ‘the immensely wealthy Mubarak Hadjiar obviously thought so, too,’ and buys out the entire matinee show at the Majestic so that his female relatives could see the film without sitting next to strange men.

However, everything is not as sunny or funny. The author’s house is stoned after a piano was brought in, as the music disturbed the faithful on their way to prayers, and her father’s good humoured tolerance does not extend to a copy of Sandro Boticelli’s ‘Birth of Venus,’ which puts him in a rage.

After turning 12, she lost much of her freedoms, which caused a depression. But she was allowed to continue schooling and managed to enter university. Migration to the US, where she began a successful career as a mental health counsellor opened another world to her.

The closeted world of Sri Lankan Muslims in the 20th century (at least until the 1970s) has to be understood in the context of the entire country with its Sinhalese majority. One can’t describe Sinhalese women of that time as being vastly more liberated. Some of the customs and mannerisms that Yasmin Azad describes, such as women referring to their husbands as ‘the child’s father,’ and women of the household peering at visitors from behind curtains, was shared by the Sinhalese, too.

The Westernised ways of middle and upper class Sinhalese women in Colombo and suburbs put them ahead of their rural sisters in some ways. 60s Lankan films capitalized on stereotype portraits of ‘decadent’ Colombo women and their pristine rural sisters. But I remember an English-educated, middle class woman from Kandy telling me that her husband did not allow her to wear even knee-length frocks or skirts and she began wearing them only after his death. (The mini skirt wave which spread into even small towns in the mid 70s needs another explanation in this context. Yasmin Azad mentions Afghan women wearing mini skirts in the same era. The National Geographic carried pictures).

The pioneering phenomenon of Vivien Gunawardhanas and Sirimavo Bandaranaikes have to be viewed and understood in this context (just like Benazir Bhutto in Pakistan), as stand out figures whose promise has not been properly realised, as the small number of women parliamentarians today and their relative insignificance goes to show.

Fortunately, literature has no such barriers and the number of women authors have proliferated. Yasmin Azad’s ‘Stay, Daughter’ is a gem of a memoir, going a long way to dispel the stereotype racial view of Muslims as ‘backward.’ It’s long overdue and I simply wonder why it took her so long to write it.