Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

I first came to know of the MiG Deal in August 2007. I was in Canada visiting family when my father called me from Colombo. He was in happy mood. He told me that The Sunday Leader had reported on a shady military contract involving Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the Air Force. My father had just watched a television interview on Derana TV in which Rajapaksa had denied having any involvement in this ‘MiG deal’. My father rambled on with details about tender procedure, inter-governmental contracts and credit letters, all of which flew well over my innocent sixteen-year-old head, as I tried without success to move our conversation towards a more father-daughter wavelength. His eye was on the prize, laser-focused on the follow-up article he was planning.

I first came to know of the MiG Deal in August 2007. I was in Canada visiting family when my father called me from Colombo. He was in happy mood. He told me that The Sunday Leader had reported on a shady military contract involving Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the Air Force. My father had just watched a television interview on Derana TV in which Rajapaksa had denied having any involvement in this ‘MiG deal’. My father rambled on with details about tender procedure, inter-governmental contracts and credit letters, all of which flew well over my innocent sixteen-year-old head, as I tried without success to move our conversation towards a more father-daughter wavelength. His eye was on the prize, laser-focused on the follow-up article he was planning.

A few days later, on Sunday, September 2, 2007, I logged on to the Sunday Leader website, as I often did, to see my father’s banner headline that the “MiG deal crash lands on defence ministry”. According to this reporting, the ‘MiG Deal’ in which Gotabaya Rajapaksa had claimed on television that he was uninvolved, was orchestrated by his cousin, Udayanga Weeratunga. It began with a meeting between Rajapaksa, Weeratunga, the Air Force Commander and one of the Ukrainian masterminds of the deal.

A few days later, on Sunday, September 2, 2007, I logged on to the Sunday Leader website, as I often did, to see my father’s banner headline that the “MiG deal crash lands on defence ministry”. According to this reporting, the ‘MiG Deal’ in which Gotabaya Rajapaksa had claimed on television that he was uninvolved, was orchestrated by his cousin, Udayanga Weeratunga. It began with a meeting between Rajapaksa, Weeratunga, the Air Force Commander and one of the Ukrainian masterminds of the deal.

That meeting with Rajapaksa, The Sunday Leader reported, took place on the February 6. It was only the next day, they said, that the Air Force suddenly developed a thirst for MiGs and the Air Force Commander wrote to the Ukrainian conspirator to ask for a proposal to sell MiGs. I have seen this letter from the Air Force Commander Donald Perera to Ukrainian national Dimitri Peregudov, dated ‘7th February 2006’. It was not even written on a letterhead. Typed in the same ‘Comic Sans MS’ scribble font with which kindergarten teachers printed posters for infants, it was little more than a childish cover-up.

This letter was supposed to belatedly transform the ‘unsolicited’ proposal that his boss’ cousin had shoved down the throat of the Air Force Commander the previous day in the Defence Secretary’s office into a ‘solicited’ one. As far as I know, no one has to date asked Donald Perera why he suddenly asked for a proposal for MiGs, having written to the Defence Secretary barely two weeks prior that the Air Force needed to consider a broad number of options, not just MiGs, in choosing its new bomber aircraft.

My father’s reporting poked at several more holes in the legitimacy of the MiG deal, from the circumvention of several standard procurement procedures, to exposing the ghost company through which the profits had been laundered, to shining a spotlight on the meddling of Rajapaksa’s cousin, Weeratunga, at every stage of the transaction.

The following month, on 18th October 2007, a lawyer for Gotabaya Rajapaksa wrote to my father threatening to sue him for defamation for causing Rs. 1 billion rupees in damage to his character. I can’t imagine that there is any way that poor Gotabaya Rajapaksa could have realised at that time that he was walking into a carefully baited trap set by the wily editor of The Sunday Leader. In Rajapaksa’s letter of demand, he said that thanks to my father’s intrepid reporting, his “role of defence secretary”, “had been adversely affected thus creating adverse consequences to the war against terror in the battlefield.”

My father responded bluntly that if that were so, Rajapaksa “should forthwith resign from the post of defence secretary” in the interests of national security. He went on to threaten to counter-sue Rajapaksa for Rs. 2 billion if he were sued, on the grounds that my father “has always remained in this country and worked for its betterment,” while Rajapaksa “has voluntarily left this country and migrated to the United States of America and taken citizenship in that country by swearing allegiance to that country.”

Throughout his career, my father was the maestro of litigation and a decorated veteran of wars of words. What he soon found himself in was a war of a more sinister sort. A couple of weeks after this testy exchange of letters, on November 21, 2007, black-clad commandos stormed the offices of The Sunday Leader, held the security staff at gunpoint with assault rifles, and set the printing presses ablaze. It will come as a surprise to none that not a soul was ever investigated, arrested or prosecuted for this pathetic act of cowardice.

Three months later, my father got the war he was waiting for. On 22nd February 2008, Gotabaya Rajapaksa filed a lawsuit for defamation against my father and The Sunday Leader, charging that the allegations made by my father against Rajapaksa were false, malicious and defamatory. By then, I was living with my father at our home on Kandewatte Terrace in Nugegoda. I was flummoxed at how he was bouncing around the house grinning from ear-to-ear in response to the news that he had been sued.

My father responded bluntly that if that were so, Rajapaksa “should forthwith resign from the post of defence secretary” in the interests of national security. He went on to threaten to counter-sue Rajapaksa for Rs. 2 billion

I looked at him more quizzically than lovingly in search of an explanation. Once he had finished whatever important phone call he was on, he turned his gaze to me and beamed. My memory of our exchange, obscured, I don’t deny, by over a decade of agony and idealization, is as follows.

“You see…” I think he started, hanging on the word “see” in a telltale signal that a sermon was to follow. “When someone sues you, they have to take the stand and be cross-examined. In any normal lawsuit, you can only ask them about things that are directly relevant to the actual case,” he explained.

“Defamation is different. If someone sues you for defamation of character, you can ask them under oath about absolutely any aspect of their life,” he went on. “He is saying his reputation is worth so much that I have done Rs. 1 billion in damages to it. Now, I can defend myself by saying that the things we wrote are true and in the public interest, which are correct.” With all my father’s notoriety for journalism, it was easy to forget, except in moments like these, that he was a lawyer at heart, and a card-carrying member of the Bar Association.

Life tip

In a nutshell, to borrow a phrase from The Sunday Leader, he said he would adopt a legal strategy of proving to the court that Rajapaksa’s reputation was worth no more than ten rupees, as opposed to one billion rupees. This he would do, he said, by exposing every skeleton in the defence secretary’s closet, by personally questioning him in a public courtroom under penalty of perjury. The proceedings, he proudly planned to publish in his newspaper to show the country who Gotabaya Rajapaksa really was. After explaining his plan, he left me with a life tip: “never, ever sue anyone for defamation,” he warned, “if you have even a single secret.”

His giddiness lasted for some months as his newspaper continued to expose scandal after scandal and put the Government on the back foot. “We have them on the run,” he would boast. Of course, we all took these boasts with a pinch of salt, because, as far as my father was concerned, he had any given government “on the run” at any given moment.

His mood only darkened in late May of 2008, after the abduction and torture of a fellow journalist named Keith Noyahr, who had himself been critical of the defence establishment. There was something strange about this incident. It had my father more worried than even the arson attack on his press. The beaming and constant optimism became more muted. In the following days I heard him whispering to people over the phone suggesting that they leave the country for their safety.

From what I know of his relationship with Mahinda Rajapaksa, which he rarely spoke of in detail outside of his innermost circle, it became clear to me that he was getting closer to the president after the Keith Noyahr incident than he had been previously. He took a lot more precautions when speaking to the President and meeting him, which, in hindsight, I believe was part of an effort by both my father and President Rajapaksa to hide their interactions from the intelligence services. I don’t have the first clue as to what the two of them discussed, but my father told me that Mahinda felt insecure and leaned on their decades-long friendship for some sort of solace.

By December of 2008, when the District Court issued an order preventing my father from writing about Gotabaya Rajapaksa, he had become a lot more fatalistic. I would ask him sometimes, like when we were curled up on his couch upstairs watching a movie, whether he was still excited about questioning Gotabaya Rajapaksa in court. He would be evasive, and on one occasion confessed to me cryptically that he didn’t think they would ever let him get that far. When I asked him what he meant, he hugged me, kissed me and reminded me that if anything were to happen to him, he had left a letter with instructions, and some money, in one of his jacket pockets in his wardrobe.

I couldn’t breathe. I don’t remember if that was because I was frightened by what he said or because he was squeezing me too tightly for me to get air into my lungs. But it was difficult to be scared or frightened around my father. He had an air of omnipresence and immortality about him. Politicians of all parties always joked that he seemed to be everywhere and knew everything. His colleagues and friends would say that he was bulletproof and untouchable. It was the following month, on January 8, 2009, that my father was proved right, and his colleagues and friends were proved wrong. He woke up that morning shortly before dawn.

My father started his morning as always getting ready with one hand while talking on his mobile phone with the other. He would interrupt his calls only to do his morning push-ups before taking a shower. He seemed not to have realised that he could put his calls on loudspeaker and leave the phone on the ground as he huffed and puffed through his thirty repetitions, which looked to me more like belly flops than push-ups.

After he had gotten dressed, we sat downstairs at the breakfast table, and he wolfed down his food before I walked him to his car and he kissed me on the forehead and drove off just like on any other day, at around 8:15 AM.

I gave our resident driver, Dias, some money to buy me a snack. He asked me to call my father and confess on his behalf that he had left his cellphone in my father’s car, which I did, shielding poor Dias from my father’s annoyance. A few hours later, I returned downstairs and asked our nanny Manika whether Dias had come back with my food. Puzzlingly, she ignored my question and avoided eye contact with me. Puzzled, but unphased, I called Dias and asked him where he was. “I’m at the hospital,” he gasped.

His mood only darkened in late May of 2008, after the abduction and torture of a fellow journalist named Keith Noyahr, who had himself been critical of the defence establishment. There was something strange about this incident

Attacked

As my heart clenched and by blood turned to ice in my veins one excruciating inch at a time, Manika turned on the television and we saw a Sirasa news anchor reporting that my father had been attacked – or shot, I don’t remember. I only remember putting two and two together: Dias being at the hospital, Manika’s strange behavior and a stone-faced news anchor saying my father’s name into the camera.

I ran upstairs to my father’s room, reached for the phone and started calling family. My aunt said it must be a false alarm. I called my mother, who lived with my brothers in Melbourne, and told her something was wrong, and that she should come to Colombo with my brothers. I waited for my father to come home and change clothes. He had been attacked, after all, and would want to change into a fresh shirt before going on television and denouncing violence against the media, like he had two days before when Sirasa had been stormed and bombed by yet another platoon of black-clad commandos.

But my father never arrived. It was only when my cousin Raisa arrived at home, her eyes watering as she sat with me in my dad’s room, that my mind tried to come to terms with the reality of the situation. It failed. I shut down and locked myself in my father’s room with Raisa. I don’t remember more about the eighth of January, except a sea of tear-strained faces and a chorus of voices repeating “I am sorry for your loss.”

The next several years of my life were defined by emptiness, agony and helplessness. I moved back to Melbourne, to join my mother and brothers. But I was rudderless. I was lonely. There is a void in the life of an adolescent girl that can only be filled by a father’s love and warmth. I spent the better part of a decade doing little other than feeling wretched over the fact that I would never again get to hug or speak to my father. After spending what felt like a lifetime living and breathing my father’s day-to-day adventures by his side, suddenly having to live without him, so far away from his orbit, in Melbourne, made me feel orphaned from my legacy and

my country.

It was almost eight years later, when I met CID detectives Nishantha Silva and Sisira Tissera in December 2016, that I fully understood the lengths to which the forces of evil had gone to in covering up my father’s murder. It was their dedication and determination that was the wind in my back and gave me the courage after so many years to dedicate my life to seeking justice for my father. For the first time since January 2009, I was inspired by men who were willing to risk their lives for justice. I felt I had found my place standing by their side.

My father was a journalist to his last breath. His last pen strokes, the CID says, came moments before his death, when he wrote down on his notebook the license plate numbers of two motorcycles, which are believed to have been those of his attackers. That notebook has vanished without a trace. In mid-January 2009, journalist Nirmala Kannangara from The Sunday Leader visited Deputy Inspector General Prasanna Nanayakkara, who was supervising my father’s murder investigation. She asked him about the notebook that she had seen with her own eyes at the crime scene. He swore to her that she was mistaken and that there was no notebook.

According to several police officers, two of whom made confessions to the Mount Lavinia Magistrate, my father’s notebook was pilfered from the evidence collection by Nanayakkara himself, who also ordered the destruction of all evidence of its existence. Nanayakkara has been arrested by the CID, but he has remained mum about who ordered him to destroy this evidence or why.

Meanwhile, in late January 2009, at the Kalubowila Hospital, the Judicial Medical Officer charged with my father’s post-mortem, Dr. K. Sunil Kumara, was putting the finishing touches on a report that falsely claimed that my father was killed by gunshot injuries. That conclusion the good doctor reached despite the absence of any bullets, entry or exit wounds, gunshot residue or shell casings anywhere on the crime scene. To prove this medical report a fiction, the CID had to exhume my father’s body and have three medical experts conduct a fresh post-mortem. They concluded unanimously that there were no grounds to suspect the use of firearms, and that my father was killed with a sharp instrument.

We don’t know for sure why Dr. Sunil Kumara, a forensic medicine expert who has thousands of post-mortems under his best, erred in his evaluation. We do know, however, thanks to the CID, that he is a close relation of arrested DIG Nanayakkara, and that the two were in close contact while the false medical report was being prepared.

It was around this same time that the oft sullen and solemn Gotabaya Rajapaksa gave a beaming television interview to the BBC, clearly thrilled to bits by my father’s demise. “Who is Lasantha Wickrematunge?” he famously quipped. “Just another murder,” he chuckled. “I’m not concerned about that,” declared the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry in charge of the police, who were ostensibly investigating my father’s cold-blooded murder.

Gota boasts of media freedom

Some months after I had left Sri Lanka, I was speaking to our driver Dias on the phone from Melbourne, and he asked me who I thought had killed my father. Based purely on my father’s own predictions, I told him it must have been Gotabaya Rajapaksa. Poor Dias, while at a tavern drowning his sorrows had repeated publicly that Lasantha Wickrematunge was killed by Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Shortly thereafter, he was abducted, bundled into a white van, taken to a safe house and threatened with certain death should he ever speak of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s involvement again. The terrified Dias fled Colombo thereafter. It was only in 2016 that the CID helped him to identify his abductor. The kidnapper turned out to be a senior military intelligence officer named Udalagama, who oversaw security for Rajapaksa’s head of national intelligence. Dias picked him out of an identification parade. Dias has lived in hiding ever since, with no support from the Government to this day.

It was, in fact, in December of 2009 that the CID first took over the investigation into my father’s murder. In less than a month, they made a breakthrough. They identified the mobile phones used by my father’s assailants and connected these five phones to the national identity card (NIC) of a poor mechanic in Nuwara Eliya named Pitchai Jesudasan. When the CID questioned Jesudasan about these phones that had been bought with this NIC in November and December of 2008, the terrified mechanic pointed out that his NIC had been stolen six months prior by military intelligence officer Kannegedera Piyawansa. This interview took place on the morning of January 18, 2018. It turns out the CID struck a nerve. That was the last they were to see of this investigation file, which was immediately yanked away from them and given to the Terrorist Investigation Division under mysterious circumstances. No one seems to know who made that happen.

My father was a journalist to his last breath. His last pen strokes, the CID says, came moments before his death, when he wrote down on his notebook the license plate numbers of two motorcycles, which are believed to have been those of his attackers

Meanwhile, according to a Sirasa News expose, on the afternoon of the same January 18, 2018, Gotabaya Rajapaksa ordered that a military officer serving in an embassy in Thailand be recalled immediately, and that a Major Prabath Bulathwatte be sent in his place. This Bulathwatte, as it turns out, was the commanding officer of the “Tripoli” military intelligence platoon whose officer Piyawansa was tied red handed to the phones used in planning my father’s murder. For some reason, the defence secretary himself was in a mighty hurry to send this man abroad, in violation of the presidential elections regulations that were in place with the polls barely a week away.

The rest of the cover up proceeded with military precision. Both Jesudasan and Piyawansa were arrested by the TID shortly after the presidential election in late January 2010. Poor Jesudasan died in custody under mysterious circumstances. Piyawansa fared a little better. Army officers are not supposed to get paid while in remand custody. But Piyawansa made history as the first ever military officer to continue drawing a salary, and receive a promotion to boot, plus over Rs. 1 million in loans from the army, all while he languished in remand custody. This accolade the army credit to an ‘administrative oversight’.

The Government launched a propaganda campaign claiming that defeated Presidential Candidate Sarath Fonseka was responsible for killing my father. Perhaps that was so, in which case the Rajapaksa Government was being awfully generous towards the former Army Commander by going to such great lengths to cover up the investigation, only to later jail him on much thinner trumped up charges.

The sad truth is that for all their dedication and hard work, most of these facts had been unearthed by the CID well before I first met the investigators in December 2016. As they drew closer to the truth in the two years since, they faced more and more bureaucratic hurdles and administrative roadblocks. Senior political leaders green and blue alike have been complicit in obstructing their investigations and providing more aid and comfort to the suspects than the investigators.

Despite the Major Bulathwatte’s Tripoli platoon having been caught red handed not just in my father’s murder, but also in the abduction and torture of Keith Noyahr a few months prior, they remain at large, still roaming free with their secret budget, weapons, white vans and motorcycles, and zero accountability. All in all, over twenty military intelligence operatives have been arrested over the involvement with abducting, killing or torturing a bevy of journalists, but neither the Army nor the Government has lifted a finger to pierce the culture of impunity in these killer squads. Evidence is withheld from the CID on “national security” grounds, even as the military intelligence apparatus keeps the CID and those who assist it under constant surveillance and continues to try and cow them with scare tactics.

The silver lining of this obsidian cloud is that it is becoming clearer by the day that covering up the truth of the “MiG Deal” was quite literally worth a killing. The FCID investigation has not only vindicated everything my father exposed about that scandal. They have gone further than he ever could have. The Ukrainian Government has told the FCID that they were not party to the agreement, and the FCID has proven that over US $7 million was stolen and laundered through shell companies in myriad tax havens. Interpol is hot on the heels of Udayanga Weeratunga, who is awaiting extradition to Sri Lanka.

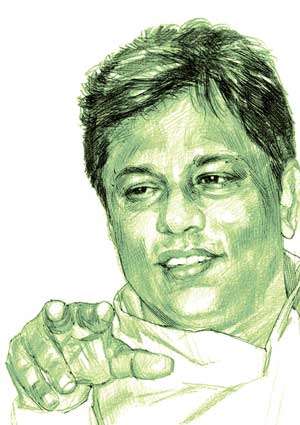

Even as various politicians have laboured to stifle the CID investigation into my father’s murder, the FCID investigation into the MiG deal has proven beyond doubt that my father was on to something when I spoke to him from Canada in August 2007. I managed to track down a copy of the interview that he was referring to on that telephone call. Gotabaya Rajapaksa, clad in a crisp pink shirt and a subdued tie, talked about the MiG deal to Derana on August 19, 2007, on their “360” programme with interviewer Dilka Samanmali. My Sinhala is beyond terrible, so I needed help with translating what I heard, but not what I saw.

After a 30-minute party-line sermon about how proper the MiG deal was, how no third party was involved and how he had nothing to do with it, and of course, after insisting that the articles about the scam were to support the LTTE and demoralise the armed forces, Gotabaya Rajapaksa shifted to the topic of media freedom. “They put my picture, and write filth,” he said. “If they can get away with that in this country, where else is there more freedom,” he went on.

“After writing these things, they can nicely drive by themselves alone on the road and nothing happens to them,” he boasted, raising and waving hands up and down in a mocking gesture of a driver holding a steering wheel. As my father, my brothers, and my entire family were to learn in the most devastating manner, this boast was ultimately no more accurate than Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s sincerest assertions about the legitimacy of his MiG deal.

(The writer is the daughter of slain newspaper Editor Lasantha Wickremathunge)