Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

- In 1992, even as Muttiah Muralitharan made his international debut, there were other brands of lemonade being made elsewhere in the country

- What began in 1991 was the decade in which the Liberation Tigers came of age as a ruthless military organisation

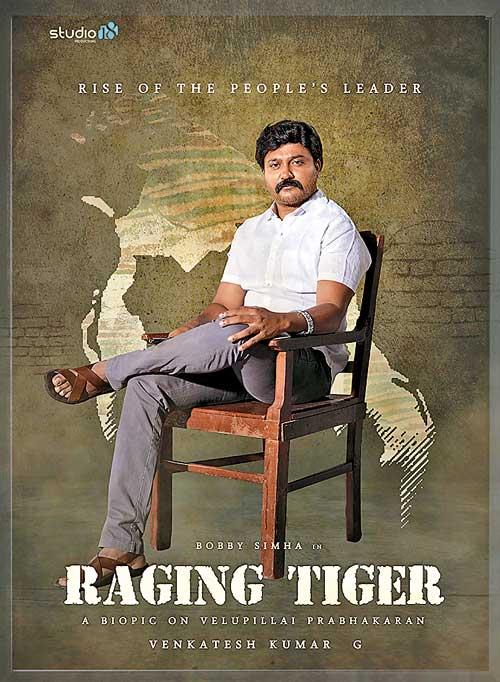

A few weeks back, YouTube chat show host Lahiru Mudalige had a conversation with three popular media figures  – Dushyanth Weeraman, Chinthana Dharmadasa, and Charith Abeysinghe – on Tamil Nadu-based Seenu Ramasamy’s film in the making “800” and Venkat Kumar’s “Raging Tiger” (Seeram Puli): a film now set to be released.

– Dushyanth Weeraman, Chinthana Dharmadasa, and Charith Abeysinghe – on Tamil Nadu-based Seenu Ramasamy’s film in the making “800” and Venkat Kumar’s “Raging Tiger” (Seeram Puli): a film now set to be released.

Set around Sri Lankan cricketer Muttiah Muralitharan, the news of “800” being produced was received with tremendous applause from local audiences which, subsequently, turned to rage when the movie lead Vijay Sethupathi came under heavy criticism from his fan base for agreeing to play Murali. Later, Sethupathi stepped down from the role and the future of the film has since been cast in doubt.

The second film, “Raging Tiger”, is said to be a biopic of a young Velupillai Prabhaharan: a nationalist icon on the rise. While the plot details of this film are yet unknown, Bobby Simha plays the lead role. Comments posted in Sinhalese on social media vehemently opposed the very notion of a film on Prabhaharan’s life who, to the imagination of Sinhalese nationalism, is the arch-villain of our “democratic socialist republic”. Talking to Mudalige, film director Charith Abeysinghe conceded that the time was not yet ripe for a film about Prabhakaran. “Sri Lanka is not prepared for a (possible) glorification of Prabhakaran,” he stressed. Even Adolf Hitler was not made into cinema until many decades after World War II, Abeysinghe claimed, in spite of being in error.

The second film, “Raging Tiger”, is said to be a biopic of a young Velupillai Prabhaharan: a nationalist icon on the rise. While the plot details of this film are yet unknown, Bobby Simha plays the lead role. Comments posted in Sinhalese on social media vehemently opposed the very notion of a film on Prabhaharan’s life who, to the imagination of Sinhalese nationalism, is the arch-villain of our “democratic socialist republic”. Talking to Mudalige, film director Charith Abeysinghe conceded that the time was not yet ripe for a film about Prabhakaran. “Sri Lanka is not prepared for a (possible) glorification of Prabhakaran,” he stressed. Even Adolf Hitler was not made into cinema until many decades after World War II, Abeysinghe claimed, in spite of being in error.

In this discussion, Chinthana Dharmadasa took a more progressive view. In Dharmadasa’s view, a film on Prabhaharan should be allowed and accepted. Regardless of our political preference, Dharmadasa emphasized that there was a need to encourage cultures with different views. Artistic expression, he conceded, should not be dictated by majoritarian sympathies. Dushyanth Weeraman attempted to look at Tamil Nadu’s opposition to “800” and the vitriol against “Raging Tiger” in Sri Lanka as two sides of the same nationalist coin.

Writing an “open letter”, the screenplay writer of “800”, Shehan Karunatilaka, expressed his frustration over Vijay Sethupathi’s exit.

Karunatilaka likened Sethupathi to a player declared out “not by an umpire’s decision” but by “the boos of the  crowd”. He called on the actor not to “cancel the match” because “a section of the crowd” was “screaming ‘no ball’”. In his response Karunatilaka poses two resonant questions: “why are we judging an off-spinner by his grasp of politics?” Karunatilaka asks.

crowd”. He called on the actor not to “cancel the match” because “a section of the crowd” was “screaming ‘no ball’”. In his response Karunatilaka poses two resonant questions: “why are we judging an off-spinner by his grasp of politics?” Karunatilaka asks.

“Do we judge Narendra Modi by his golf swing or Mahinda Rajapaksa by his goal kicking?” And more imposingly: “If we wanted to tell the tale of Thiruchelvam or Thiranagama or Karuna or Prabhakaran or Kadirigamar or Elara, will the politicians and media of Tamil Nadu not allow us to?”

Of course, in asking those questions, Karunatilaka chooses to be a tad naïve. While the golf swing or the goal kicking of a politician cannot be fried in the same pan as the politics of an athlete, by asking us to view Muralitharan refracted from his politics Karunatilaka proposes to no-ball the intelligence of the world. Can one divorce Muhammad Ali from his political endorsement of Black American rights? Can a discussion of Zimbabweans Andy Flower and Henry Olongo be wholesome without their protest against Mugabe’s dictatorship? Tamil Nadu’s rage against Sethupathi comes from a national consciousness that permeates geo-political nation-state boundaries. It comes from national-minded zealots of that vast Tamil land’s political chessboard against a Sri Lankan upcountry Tamil who – without his knowing it – is in himself a cultural complex.

Murali’s South Indian genealogical is less than a century old. The entrepreneurial gene that percolates the Muttiah family makes of Murali’s father a successful businessman which, in turn, enhances the fortunes of the family. Murali had his education at a prestigious Kandy school where he emerged as a cricketing prodigy in the late-1980s. In a career that covers the better part of two decades, Murali became the bowler with the best statistical record of all time. Medical tests proved his arm to have a permanent bent. In our lifetime, Murali taught the world to  make lemonade when life provided one lemon. Having conquered the cricketing kingdoms Murali then turned to South India and got married.

make lemonade when life provided one lemon. Having conquered the cricketing kingdoms Murali then turned to South India and got married.

In 1992, even as Muttiah Muralitharan made his international debut, there were other brands of lemonade being made elsewhere in the country. Under President Premadasa’s watch, the Indian Peace Keeping Force had just repatriated. Rajiv Gandhi had been killed. The country’s north and east were being exposed to the Liberation Tigers. What began in 1991 was the decade in which the Liberation Tigers came of age as a ruthless military organisation. But, as widely documented, what took a sharp militant bent post-1976 was a twenty-year democratic struggle for political representation and linguistic prestige. Between 1956 and 1976, two pacts had been signed and repealed to restore the prestige of the Tamil language. These were unfortunate cancellations – long before Vijay Sethupathi – where the State was pressured by Sinhalese zealots. Midwifed by exclusionary politics and ethno-nationalistic alienation, the political birth of Prabhaharan happened in the mid-1970s (I hope Venkat Kumar captures these passages in his film.)

In his documentary “Indian Blood for Tamil Eelam”, Nandana Weeraratne explores the fates of hundreds of upcountry Tamil families that were displaced by riots in the 1970s. Chased away from their upcountry homes, they resettled in the Vanni as a marginalized community. Weeraratne concedes that the Liberation Tigers drew cadre from this poor, socially rejected enclave. These cadres were used in elite Tigers divisions in its war against the state.

For me, the question is not about what films should be made (or what should not). In our need for expression, films are in any case made. The question is about centring films that are made in the margins. That is the question – the pertinent question.