Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Sri Lanka must integrate with global production networks that require trade reforms, removal of tariffs and protections across sectors and joining free trade agreements.

I hope to convince the reader that despite some of the commentary, Sri Lanka is not on the road to recovery. Numerous predictably dysfunctional policies with questionable rationalisations were implemented in 2019 and 2020; there was no discernible deliberative process. The underlying fragility of governance that precipitated the collapse is still prevalent. Two years on, the Wickremesinghe Government is exhibiting the same tendencies: a concentration of power in the office of the presidency with the executive holding the critical ministries of finance and defence; this Wickremesinghe Government has not materially altered the conditions that led to our crisis.

were implemented in 2019 and 2020; there was no discernible deliberative process. The underlying fragility of governance that precipitated the collapse is still prevalent. Two years on, the Wickremesinghe Government is exhibiting the same tendencies: a concentration of power in the office of the presidency with the executive holding the critical ministries of finance and defence; this Wickremesinghe Government has not materially altered the conditions that led to our crisis.

During an appearance on Newsfirst’s Face the Nation in October last year, Deputy Executive Director of Transparency International, Sankhitha Gunaratne noted that Sri Lanka’s was not simply an economic crisis but a “long-lasting governance crisis… what do we mean when we say governance? We mean checks and balances, separation of powers… decentralisation of powers, not further centralisation… we mean the freedom of people to dissent… protest without fear of reprisals… corruption is not just economic crime… abuses of process, conflicts of interest, hiding behind opaque structures, disabling the governance infrastructure of the country, capturing state institutions/ policies/ laws for the interests of a few…”

President Wickremesinghe’s commitment to “tough and unpopular decision-making” has been confined to raising taxes within a regressive structure, increasing energy costs, concentrating power in the Executive Presidency and perpetuating ‘Pohottuwa’ control over the Cabinet.

Here is a limited list of difficult decisions the President and the Government have not taken:

The Long Road to Nowhere

It is easy to criticise the government and the reader is justified in asking what possible alternatives are available to the current economic plan. It is necessary to first acknowledge the weaknesses of the current trajectory. Here are some basic propositions:

I submit that the above, sufficiently broad statements are neither conjecture nor opinion, all of these are covered in publications by major international organisations.

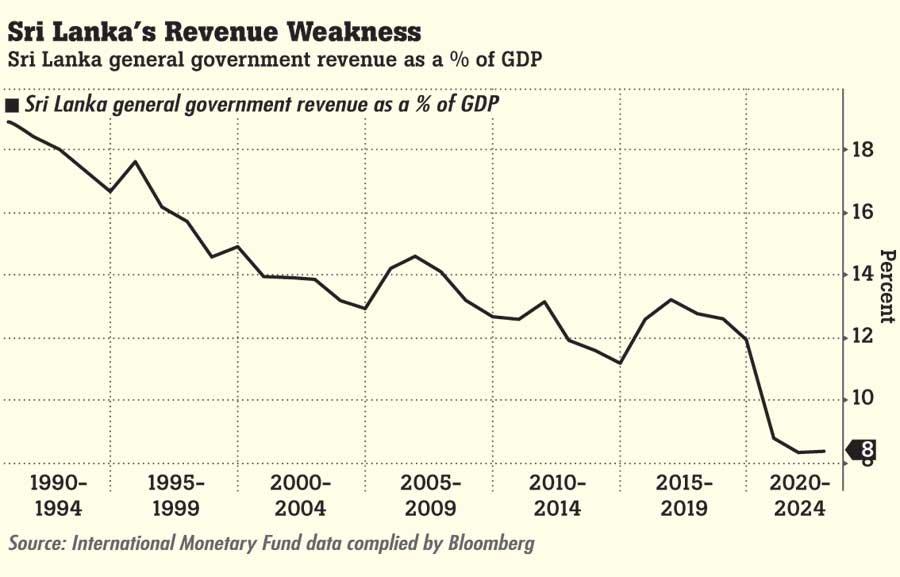

In the early 1990s, Sri Lanka generated tax revenue to GDP of 18-19% with a downward trend ever since. The tax cuts, (3) above, brought this ratio down to 7.4% in 2020.

When President Ranil Wickremesinghe was Prime Minister from 2015 to 2019; his government entered into an IMF Programme and committed to raising tax revenue as part of a fiscal consolidation programme. It was against this backdrop that ‘Yahapalanaya’ delivered perhaps its most progressive piece of legislation; the 2015 one-off super-gains tax on profits over Rs. 2bn for the previous financial year, for individuals and companies.

Yahapalanaya also passed the Inland Revenue Act in 2018 and having come to power in 2015, the Wickremesinghe Government achieved the following tax revenue to GDP:

11.7% - 2015

11.4% - 2016

11.6% - 2017

11.2% - 2018

The Government of 2015 failed to generate anywhere near the required growth in tax revenues. Today, as Sri Lanka teeters on the brink, policy makers have agreed on a plan with the IMF that imposes a time-restricted fiscal consolidation with tax revenue to GDP projected to reach 15% in each of the three years leading up to 2028.

As per the current program, the IMF’s own projections show Sri Lanka with higher Foreign Debt to GDP in 2028 (70%) than we do today (68%) and higher external debt in absolute terms relative to today ($55bn vs. $65bn). The IMF’s plan envisions Sri Lanka regaining access to capital markets, utilising International Sovereign Bonds that left the treasury vulnerable to rollover risks and have now complicated our debt restructuring negotiations.

The question remains, where does the current path lead? It has stabilised the economic and social downward spiral while simultaneously allowing the government to return to a business-as-usual setting. It provides assurances to bilateral and private creditors and satisfies the rating agencies. It has also transferred the costs of reforms onto a broad section of society, with little effort to target the wealthiest in our economy. Most importantly, it has failed to extract even basic concessions to stronger governance structures.

A Governance Reset

President Ranil Wickremesinghe is the Cabinet Minister of Finance, Defence, Technology and Women, Child Affairs and Social Empowerment. UNP Stalwarts from Akila Viraj Kariyawasam (Senior Advisor to the President), Ruwan Wijewardene (Presidential Advisor on Climate Change), Vajira Abeywardena (National List MP), Sagala Ratanayake (National Security Advisor) have all been elevated into positions of power.

Based on the evidence and trajectory, the current plan is not going to achieve much beyond debt sustainability, will likely not deliver improvements to material conditions for the poorest nor generate growth rates that rescue the Sri Lankan middle class. This is not the fault of the IMF. Sri Lanka requires action on revenue and governance that will seem radical but only from a Sri Lankan perspective, a context of completely incoherent economic policies and damaging incentives. Much of the radical alternative involves common sense checks and balances; a governance reset.

The first step on the path to a Governance Reset is acknowledging and acting upon the situation on the ground. The 2019 tax cuts led to the Treasury losing out on an estimated Rs.700bn of tax revenue in a single year. Where did this money go?

On the one hand, we know that Sri Lanka’s corporates and high-net-worth individuals do not generate tax revenue at the levels of counterparts in other comparable countries.

On the other hand, we also know, from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) research that Sri Lanka is among the top five most unequal countries in the Asia-Pacific region; the top 1% of income earners in Sri Lanka own as much as 30% of total private wealth and the bottom 50% of income earners own less than 4% of total private wealth.

These are statistics but anecdotally, most people reading this English daily newspaper will have noticed that restaurants and retail seem to have traffic, that consumers are out and businesses are getting back on their feet, but you will also notice increased homelessness, closed shops on main roads, buildings with ‘To Let’ signs; all alongside luxury vehicles and two million dollar apartment units.

Sri Lanka must continue the IMF-prescribed fiscal reforms, SOE divestiture and state-sector employee rationalisation. Yet, in many other ways, Sri Lanka must reach beyond the IMF program, beginning with a radically different tax structure by raising more revenue from wealth, capital gains, transactions and reducing the burden on the middle class and working people.

This is the story of a divergent economy; it is a manifestation of growing disparities in incomes and living standards. Once you accept that (a) the current IMF centred trajectory only provides interim relief for the economy while it achieves debt sustainability (b) adequate measures have not been taken to eradicate the underlying governance deficits, it is then possible to ascertain the alternatives.

Sri Lanka must continue the IMF-prescribed fiscal reforms, SOE divestiture and state-sector employee rationalisation. Yet, in many other ways, Sri Lanka must reach beyond the IMF program, beginning with a radically different tax structure by raising more revenue from wealth, capital gains, transactions and reducing the burden on the middle class and working people.

If Sri Lanka can increase the tax-to-GDP ratio to closer to 20% instead of the IMF-projected 15%, it allows the Government to pay off debt faster while also funding healthcare and education. A higher tax to revenue base would also allow the Government to provide targeted social protections to Sri Lanka’s increasingly desperate sections that have fallen below the poverty line.

Peering over the fence

Sri Lanka’s long-term viability depends almost entirely on our ability to increase foreign exchange inflows and address the decades-long trade deficit. While garments, tourism, tea and foreign remittances are crucial flows, our economy must generate fresh industrial sectors. Sri Lanka’s export product mix has not diversified since the Premadasa-era garment industry. Many other countries including Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia considered ‘late-stage’ industrialisations have followed on from the success of industrialisation drives in Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong.

foreign remittances are crucial flows, our economy must generate fresh industrial sectors. Sri Lanka’s export product mix has not diversified since the Premadasa-era garment industry. Many other countries including Vietnam, South Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia considered ‘late-stage’ industrialisations have followed on from the success of industrialisation drives in Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Every major Asian economy that might be considered an economic success story has some history of industrialisation. Take a look at the foreign exchange reserves of some industrialised Asian Economies as of March 2024:

Global trade networks

The countries below Sri Lanka on this list have all industrialised their economies to some extent and are part of global trade networks and free trade areas. The accumulation of foreign exchange reserves can cushion such economies from major external shocks.

Sri Lanka must integrate with global production networks, so-called production fragmentation; this requires significant trade reforms, removal of tariffs and protections across sectors and joining free trade agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). It is a delicate project to ensure that foreign capital investments in high-technology sectors also facilitate expertise and technology transfers and benefits; local industry; skill enhancements; research and development. This will require targeted, well-defined, limited and non-permanent industrial and energy subsidies to incentivise local private capital and foreign investment capital into sectors that the Government deems critical to building high-technology export- oriented sectors.

None of the above can occur unless Sri Lanka’s policy apparatus is free from external coercion of special interest groups and business lobbies; protections for some sectors will need to be discontinued. All this only occurs in the context of strict governance and strategic policy planning that is deliberative and based on a multi-level stakeholder consensus.

The government must ensure there is a protective firewall between policy-making and short-term business imperatives.This can partly be achieved through better transparency of decision-making deliberations and criteria.

Sri Lankan policymakers must also look beyond the current dashboard of indicators that are being used to judge the economy to include different measures to track the impacts of policy on specific societal issues; Gross Domestic Product (GDP), currency rates, unemployment, primary account balances are not well-rounded measures of an economy and its underlying societal health.

Sri Lanka should instead focus on improvements to inequality and income disparities perhaps through gini coefficients or various other indices such as the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index. We should measure improvements to our education system through the availability of accessible education, or of the healthcare system through health outcomes and quality measures.

I would urge the reader to reconsider the narratives surrounding the current trajectory and discourse of stability and progress and consider reasonable alternatives from political parties. Sri Lanka can achieve much more if we have strategic policies that are not captive to international organisations and local business interests. This is not as elusive as it seems, we have countries that have suffered the same failures resulting from similar structural weaknesses. The difference so far has been that policymakers have been unwilling to peek over the fence and learn from the world around us; from Karnataka to Saigon, nations have already generated the blueprints for industrialised export development, Sri Lankan policymakers must adapt these so Sri Lanka becomes the new Asian Tiger Economy.