Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

In 1156 AD, the third year of his reign, Parakramabahu I faced a revolt in Ruhunurata led by Sugala, whose son Manabharana had been defeated and vanquished by him. He directed two of his Generals, Damiladhikari Rakkha and Kacukinayaka, to take two routes to Ruhuna and subjugate the aspiring queen. Codrington speculates that the latter general, after suffering defeat at Mahavalukagama (Weligama), eventually proceeded to Devanagama (Dondra) and from there to Kammaragama (Kamburugamuwa), Mahapanalagama, Manakapiththi, the ford of the Nilwala River, and Kadalipatta.

In 1156 AD, the third year of his reign, Parakramabahu I faced a revolt in Ruhunurata led by Sugala, whose son Manabharana had been defeated and vanquished by him. He directed two of his Generals, Damiladhikari Rakkha and Kacukinayaka, to take two routes to Ruhuna and subjugate the aspiring queen. Codrington speculates that the latter general, after suffering defeat at Mahavalukagama (Weligama), eventually proceeded to Devanagama (Dondra) and from there to Kammaragama (Kamburugamuwa), Mahapanalagama, Manakapiththi, the ford of the Nilwala River, and Kadalipatta.

The other took the route through Ratnapura. His army encountered defeat in the two territories they conquered first, reclaiming both as soon as they could and advancing to Magama and thence to Beralapanatara. Codrington speculates about his itinerary too: Damiladhikari may have gone through the mountains between Rakwana and Deniyaya, or he may have gone through the mountains of the Kolonne Korale on the fringes of Ratnapura District. Having reached Koggala, Damiladhikari proceeded to Magama, where, after a series of battles with the rebels, the war was won.

When Damiladhikari’s troops marched through Ratnapura, the two territories they captured first were Donivagga (Denawaka) and Navayojana (Nawadun). From there we are told they advanced to Kalagiribanda or Kalugalbodarata, encompassing the Kukul, Atakalan, Kolonna, and Morawaka Korales; from there, to the Atakalan Korale, Dandava between Kahawatte and Opanayake, Tambagamuwa near Madampe, Bogahawela, Binnegama, and finally Butkanda. Nawadun (roughly the Nawadun Korale of today) was thus the army’s first priority. It was here, long, long before Parakramabahu and Polonnaruwa, that the first puskola poth on which the Tripitakaya would be written were made.

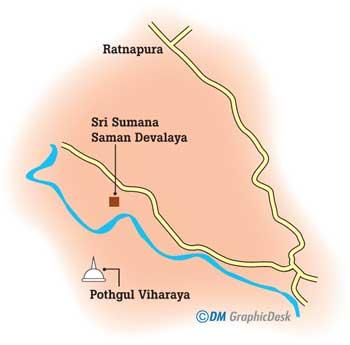

Three kilometres from Ratnapura town you turn to your right to Elapatha, one of the 17 Divisional Secretariats in Ratnapura. Though barely enough for two vehicles to pass one other, the road goes on for another four kilometres before you reach a village called Karangoda. Reputedly the name given to the remnants of ola leaves after they’ve been used to make books, Karan-goda, located in Elapatha – in turn in Nivithigala, Pallepattuwa, Nawadun Korale – is where you come across a viharaya less well heard of, I suppose, than the most minor architectural accomplishments of Parakramabahu: Pothgul Viharaya. Here, during the reign of Watta Gamini Abhaya, the first talipot books were put together for the Fourth Buddhist Council. There’s controversy about where the texts were written down: some say at the Alu Viharaya at Matale, others say at the Alu Lena in Kegalle. Either way, it doesn’t matter: the books were made elsewhere.

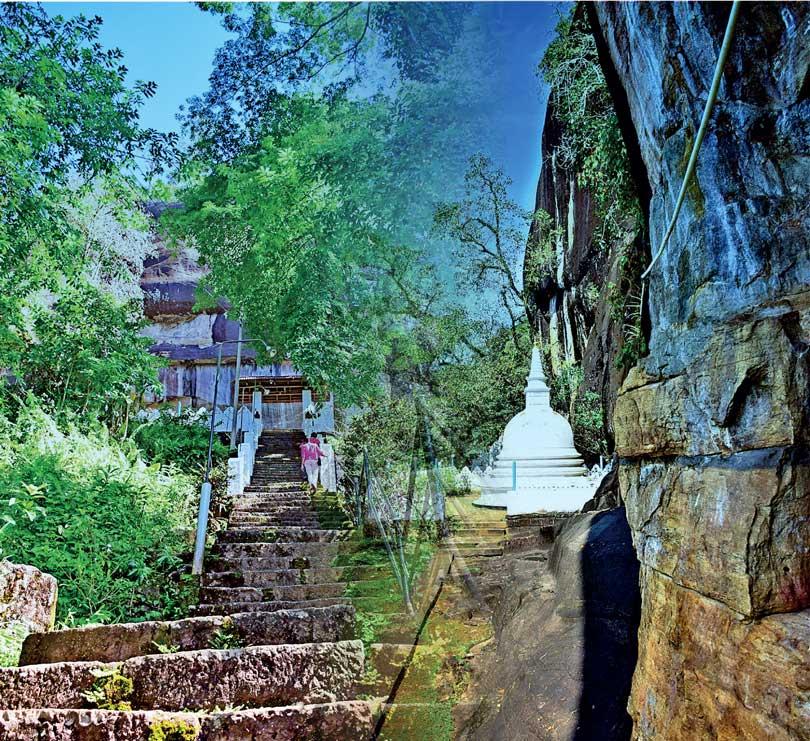

There are several ways of reaching Pothgula; I took the easiest, which is getting down from the bus at Karangoda and taking a tuk-tuk for about one and a half to two kilometres. There are two temples: a dharmashalawa down below, and the main viharaya to get to which you have to climb 460 steps: the guide to the temple, a 16-page pamphlet sold for Rs.100 (it’s worth it, trust me), puts the number at 469. Locals call this the second Sri Pada, reasons for which I will get to shortly, though for me the association comes off in the fact that as with that peak which it hardly resembles, one has to climb an endless series of steps to complete the ascent.

I know I’m complaining, and I shouldn’t: compared to Dambulla and Sigiriya, this is a much shorter climb. But then everyone visits Dambulla and Sigiriya, and no one seems to have even heard of Pothgula – which is why you shouldn’t miss what awaits you at the top. But first, some history. When Valagamba was defeated and chased away from Anuradhapura, he was followed by his most faithful subjects.

Among them, a monk: Kushikkala Tissa. He settled near Karangoda with his disciples and other refugees from Anuradhapura. Meanwhile, in a village nearby, a sentry in charge of the Sri Maha Bodhiya by the name of Bodhinayake founded his own settlement: the village of Weragama. The Weragama Bodhinayake walawwa stands there today, and according to the pamphlet, “those who hail from the Bodhinayake line continue to reside in the area.”

Among them, a monk: Kushikkala Tissa. He settled near Karangoda with his disciples and other refugees from Anuradhapura. Meanwhile, in a village nearby, a sentry in charge of the Sri Maha Bodhiya by the name of Bodhinayake founded his own settlement: the village of Weragama. The Weragama Bodhinayake walawwa stands there today, and according to the pamphlet, “those who hail from the Bodhinayake line continue to reside in the area.”

I wouldn’t doubt that. With a monk, there inevitably follows an order of monks, or a sangha parapura. Given the Pothgula’s importance, it made sense to appoint as its chief incumbent those who officiated as chief incumbents in neighbouring temples and religious places. The Pothgula hence came to foster other temples: five of them, according to the pamphlet, including the Marapana Purana Viharaya and the Kiriella Raja Maha Viharaya.

These in turn branched out to other temples, two of them under the Kiriella Viharaya. The sangha parapura, in the meantime, flourished: we hear next of a chief incumbent whose contribution to the Buddhist revival of the 18th and 19th centuries has been scantily noticed: Vehalle Sri Dhammadinna. This was at a time when Ganinnanses or lay monks (comparable to the Achars of Cambodia) had taken over the duties of monks: “clad in white robes”, they “observed dasasil, looked after the destroyed Buddhist monasteries, and attended to the community needs of Buddhists.” But the decline continued, and during Sri Vijaya Rajasinghe’s reign we come across only two among 33 higher ordained Bhikkhus producing students capable of continuing the parapura. Of the two, Suriyagoda Kitsirigoda, the Rajaguru and Dhammanusasaka of Narendrasinghe, ordained Weliwita Saranankara, who revived Buddhism in Kandy.

The other, Kadurupokune Navaratne Buddharakkitha, resided in Tissamaharama down south, ordaining two disciples. One of them, Sitinamaluwe Dhammajoti, became the last non-Govigama monk to be initiated into the Siyam Nikaya. The other was Vehalle Dhamadinna, who with Dhammajoti began a campaign to revive Buddhism in the littoral regions. In 1753 when the upasampadawa was established under Kirthi Sri Rajasinghe and Buddharakkitha’s students were ordained into the Siyam Nikaya, Dhamadinna, who took part in the upasampadawa with 22 Ganinnanses from Sabaragamuwa and 20 Ganinnanses from Matara, was 74; he would have been 97 when he passed away in 1776. His parapura included Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala.

Back to the temple. The pamphlet tells you of a tunnel just behind the Buddha image at the main viharaya, but according to locals there’s a second, longer one, sealed off after someone tried to test the theory that it leads to the Ehelapola Walawwa in town and lost his way, never to be found again. The cave that’s not sealed off doesn’t take one far, and in any case, it’s not nearly as interesting as that other artefact in the viharaya: an ulpatha, known popularly for its healing properties (plastic cups on a table right beside it indicate how people believe this), yet dismissed by locals as a convenient fiction. (Apparently there’s a snake lurking in the water and a child had once fallen into it; the child had climbed back, and the snake had stayed put.)

Also taken as a convenient fiction is the view that Valagamba hid his family here; a local told me that given what that king did for Buddhism, temples nearly everywhere went on claiming that he and his family were sheltered by them. We’ll obviously never know for sure. Apart from the tunnel, viharaya, and jala ulpatha, to the left there’s a waterhole where monks would have bathed in back in the day; to the right, there’s a bodhiya and a not so large stupa, beyond which you come across another, smaller viharaya. In the month of Navam right until the end of the year, according to the pamphlet, the area is surrounded and secured by wasps. I saw one of these creatures – the first time up close – its back turned haughtily to me. I should have no reason to fear, I suppose, at least according to the book: apparently only sinners and desecrators get stung, only to meet a far worse fate (death? – the book never specifies) after they leave the premises.

In that case a whole lot of teenage lovers would have met the sting of the wasp, judging by the many X-Loves-Y-s chalked on the rocks. Roland Raven-Hart didn’t think much of Ratnapura: he found it “consistently hot and rainy”, an “uninteresting place except for the gems.” Bella Woolf, travelling through the island half a century before him, agreed: “the climate... is aptly compared to a Turkish bath.” I found it hot and humid too – no doubt like a Turkish bath. But uninteresting? Not on your life. I spent my Christmas there, at Raddella near Karangoda, for three days and nights – not one firecracker on Christmas Eve – and the people tend to make up for whatever shortcomings in the weather. Those people still hold on to their earlier ways of life – and their dialect, which intrigued me (Osmund Jayaratne, campaigning for the LSSP in the region, was confused when he was offered a maluwa and was instead served vegetable curries; unlike in the south, but like in the former areas of the Kandyan kingdom, including Kurunegala, curries are referred to as “maluwa”) – though modernity has found its way in: people judge distances in terms of bus fares, they are sceptical about magic and superstition, they hold contrasting views even within the same family. It’s gem country alright, but if you’re here just for the gems, you’ll leave dissatisfied, like going to Ambalangoda merely to see the masks.

There’s so much more out here – so much more waiting for you. The writings of H. W. Codrington, M. U. de Silva, C. W. Nicholas, Roland Raven-Hart, Bella Woolf, Kamalika Pieris, and Vinod Moonesinghe were used for this article.