Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

A villager in a British colony who knew no English picked up only two words – yes and no. But he did not know the meaning of the two words. One day he was arrested for a crime he did not commit. When he was produced before the magistrate, of course an Englishman, the villager thought he would be freed if he answered the questions in English.

A villager in a British colony who knew no English picked up only two words – yes and no. But he did not know the meaning of the two words. One day he was arrested for a crime he did not commit. When he was produced before the magistrate, of course an Englishman, the villager thought he would be freed if he answered the questions in English.

The judge asked him: Did you commit the crime?

Villager: Yes.

Judge: Was there anyone else with you?

Villager: No.

Judge: Do you realise that you have to go to jail?

Villager: Yes.

The poor villager realised his folly only when he was taken to prison.

The moral of the story is: You may be asked to say simply yes or no to a question, but say it with a proper understanding of the question.

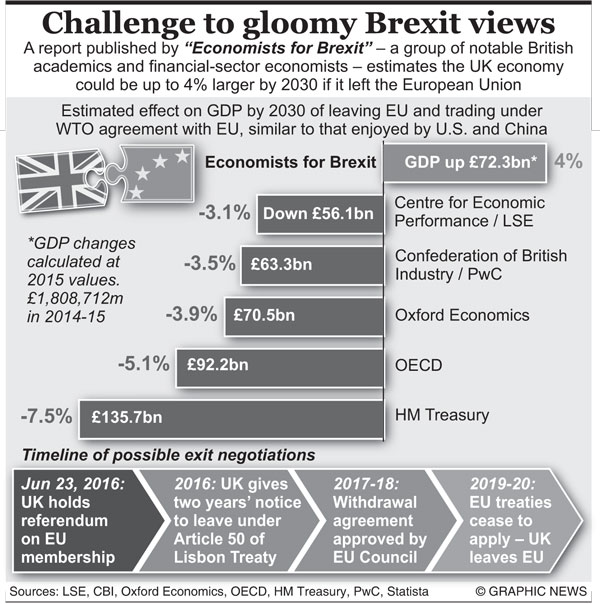

The story is more relevant to the British people who will be answering yes or no at a destiny-changing referendum on June 23.

The question before them is: Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”

This may be a question addressed to the British people, but the result of the referendum could shake the world economic order. With opinion polls indicating that the British people are evenly split over the question, the anxiety in European capitals is reaching fever pitch.

Worried about Britain’s exit from the 28-member European Union – Brexit – and its impact on the world economic order, where the West’s domination is waning due to the economic rise of China, United States President Barack Obama and the leaders of Germany, France and other EU countries have appealed to the British people to vote yes and stay in the Union.

But for the British people, the issue is more domestic rather than one that concerns the dwindling European clout in world economics.

The call for a Brexit gained momentum in Britain with the rise of nationalistic political parties such as the UK Independence Party in the past five years or so.

They argue that the British people have not had a say since 1975, when they voted to stay in the EU at a referendum. They say their lives have increasingly been controlled by anti-British EU laws that allow migrants from less affluent EU nations to get British jobs, and refugees from the Middle East to change Britain’s demography. They also argue that the returns from the EU are not commensurate with 7.2 billion pounds Britain pays as annual membership fee.

The debates over Britain’s EU membership became so intense that Britain’s mainstream political parties – the Conservative Party, the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats – found it difficult to ignore the issue anymore.

With growing calls from his own Conservative Party for a referendum, Prime Minister David Cameron promised to hold one if he won the 2015 general elections.

Though initially seen to be pro-Brexit, Cameron now vigorously campaigns to keep Britain in the EU. In a desperate attempt, he held crisis talks with EU leaders in January and February to negotiate a special-status deal for Britain. The deal which got the EU nod will allow Britain to give primacy to domestic laws over EU laws in matters such as migration and refugees.

But Brexit supporters scoff at what Cameron tries to show as concessions from the EU, the world’s biggest economic power.

European integration had its genesis in the Council of Europe. Formed in August 1949, the Council headquartered in Strasbourg, France was one of the first post-war regional organisations and it was seen as a first timid step in the direction of creating a ‘United States of Europe’.

The second step was bold and it came when Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany formed the historic European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1952.

In 1958, the six countries launched the European Economic Community (EEC), an ambitious project commonly known as the Common Market. This was preceded by the formation of the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). The three institutions -- the ECSC, the EEC and the Euratom -- integrated into a single massive organisation called the European Community (EC) in 1967. Britain joined the EC in 1973.

The next big step was the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. It paved the way for the European monetary union, though Britain opted out of it. Thus was created the largest economic power on earth, with a huge market. Member-states ignored questions on sovereignty in the larger interests of European integration with the EU being seen as a one-stop solution store for Europe’s socio-economic problems.

The EU’s success made European federalists to dream of a political union – the United States of Europe. They argued that integration had promoted peace and security between member states since the end of World War II in Europe in 1945. Moreover, whenever conflicts arose in the continent, the EU has rushed to make peace, as happened during the Yugoslav and Kosovo conflicts.

But the EU’s problems started with its rush to give membership to former communist countries in Eastern Europe. Strict rules were bent to accommodate new members, while Turkey which had been seeking membership for the past three decades or so, was spurned.

The haphazard membership policy was also blamed for last year’s Greek debt crisis. Richer European nations were forced to rescue Greece, every time it fell into a debt crisis because they feared that if they let Greece exit Eurozone – the media called it Grexit -- and evade repayments of its loans, the repercussions would be equally disastrous to their economies.

The Greek debt crisis and later the refugee influx from Syria only strengthened the voice of eurosceptics and neo-Nazis.

In any case the implications of Britain’s referendum will be global, whether the outcome is yes or no. If yes, Britain will stay in the Union but with a special status. This may lead to a situation where other nations demanding similar concessions, eventually making the EU a toothless economic giant.