Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

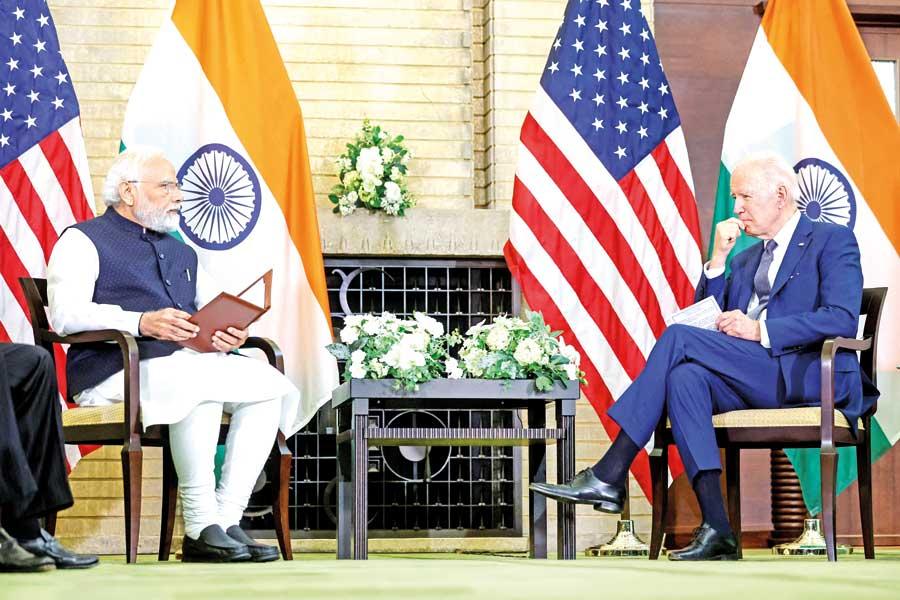

Indian Premier Narendra Modi was flattered with a red-carpet welcome, a state banquet and a rare honour of being invited to address a joint session of the Congress, for yet another time.

Five years back in China, I submitted my doctoral dissertation, having chopped off two complete chapters on my supervisor’s advice to be on the safe side for both of us. It was an analysis of competition for power and influence by China and India in South Asia. Given the vast power asymmetries between the two regional powers, I titled it ‘an uneven contest’. India’s economy then (and now) is barely one-fifth of China’s measured in nominal US$.

of competition for power and influence by China and India in South Asia. Given the vast power asymmetries between the two regional powers, I titled it ‘an uneven contest’. India’s economy then (and now) is barely one-fifth of China’s measured in nominal US$.

What a difference five years could make! Power disparities between the two competing regional powers have not changed. The Chinese economy, at US$ 17.7 trillion, is still nearly four and half times India’s. India’s economic growth rate has momentarily overtaken China’s. Still, even if the Indian economy continues to outpace China by a modest margin, the power differences, though lessened, would persist for several decades into the future.

But, the pendulum of economic growth is gradually shifting from China to India. Geopolitics serves New Delhi most profoundly as well. India would probably be the only large country to benefit from the West’s call for global companies to decouple/ de-risk from China, thereby diversifying hitherto China-dependent supply chains. Though countries such as Vietnam and Mexico are reaping the immediate benefits of supply chain disruption and diversification, India has the greatest absorption capacity for sustainable long-term relocation of supply chains when the trend persists. It also has the geopolitical heft to justify its piece of the pie.

"Since India’s nascent economic liberalization, which unshackled the Indian economy, many observers have rather prematurely termed different epochs as India’s shining moment. However, the coming decade or so could be India’s shining moment"

Last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi concluded a state visit to Washington, where he was flattered with a red-carpet welcome, a state banquette and invited to address a joint session of the Congress, for yet another time, a rare honour accorded to those like Winston Churchill. PM Modi was showered with defence deals, including domestic production of General Electric’s jet engines. He signed a long list of joint initiatives on telecommunications, semi-conductors, artificial intelligence and space exploration. The critics had a field day, too, criticizing India’s human rights record, some of which are rather overblown. However, none of the self-righteous advocacy could mask the ensuing shift in the balance of power in the region and the wider world and India’s pivotal role as a hedge against China.

Since India’s nascent economic liberalization, which unshackled the Indian economy, many observers have rather prematurely termed different epochs as India’s shining moment. However, the coming decade or so could be India’s shining moment.

Other than favourable geopolitical tailwinds, the demographic windfall of India, now the most populous country, would provide for long-term growth if it creates opportunities for its bulging youth population. India is currently sitting at a growth sprout similar to China’s in the first decade of this century. The catalyst of China was Beijing’s admission to the World Trade Organization in December 2001. During the next decade, the Chinese economy grew nearly six-fold (US$ 1.5 trillion in 2002 to 8.5 trillion in 2012).

China’s economic rise also spilt out of the mainland, creating supply chains running from Taiwan to Mekong Delta, turning Vietnam into a rising manufacturing powerhouse, and even reaching Cambodia and Myanmar.

The importance of international politics as an academic discipline is not parroting theories eloquently. Rather it gives analytical insights to predict and interpret the systemic signals and device means to benefit from systemic opportunities as well as to mitigate systemic risks.

Such risks and opportunities do not need to be security oriented. The examples of the recent history of political economy, ranging from South Korea, and Taiwan to Singapore and Thailand, would reveal that much of those systemic opportunities had been translated into fate- defining economic opportunities by skillful leaders.

Any commonsense Sri Lankan politician or a policymaker who sees India should be able to see an elephantine opportunity. However, unfortunately for a country where the main remittance is from unskilled and semi-skilled workers toiling in the Middle East and Korea, Sri Lankans have an unusual superiority complex. Our IT workers previously opposed a proposed Economic and Technological Cooperation Agreement (ETCA) with India, fearing Indian techies, who account for one-third of all engineers of Silicon Valley, would flood the country. The naysayers are also foul-mouthing the proposed linking of the electricity grid with India; others oppose the development of the tank farm in Trincomalee and the cooperation with the Adani group on renewable energy.

Some of the Sri Lankan grievances, such as the sloppy deal it got under the Indo-Lanka free trade agreement, are understandable. In its own right, India is not known to lead the flock in trade liberalization, like other major states tend to do. As a result, South Asia remained the least connected region in terms of interregional trade. But, as its economic heft grows, so would its confidence, and one might expect India to proactively promote regional trade and service integration.

Sri Lankan economy, interlocked with India’s, would be better equipped to benefit from India’s rise. Consider India’s global industry of IT services, which is valued at US$ 200 billion annually. What is stopping Sri Lanka from integrating its own with the world’s 7th largest service exporter? Sri Lanka’s IT services account for barely US$ 1.2 billion and have tremendous room for growth in its educated workforce. Our cities are way more livable than their Indian peers. What is stopping large Indian IT powerhouses from opening shop in Sri Lanka, if not for our own prohibitionist instincts and the sheer absence of initiative?

Everyone who’s anyone in Sri Lanka’s chattering circles now talks highly of the industrialization of Vietnam and Bangladesh and promises to replicate the same in Sri Lanka if they come to power, ignoring the fact that those are countries with a population of several times Sri Lanka. Considering its labour cost and labour shortage, Sri Lanka, on its own, is unlikely to be an enticing destination for light manufacturing. Probably such deficiencies could be mitigated, and industrial clusters that support supply chains of more advanced level could be nurtured by integrating ours with India’s.

Unfortunately, Sri Lankan political class lacks initiative and self-defeatist conspiracy theories cloud public discourse. President Ranil Wickremesinghe has touted his desire for economic liberalization; he repeated the promise at the International democratic union last week. He should see the enormous economic opportunity rising India holds for its smaller neighbour. He should proceed to seize that opportunity.

Follow Ranga Jayasuriya @RangaJayasuriya on Twitter