Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Photos by Manusha Lakshan

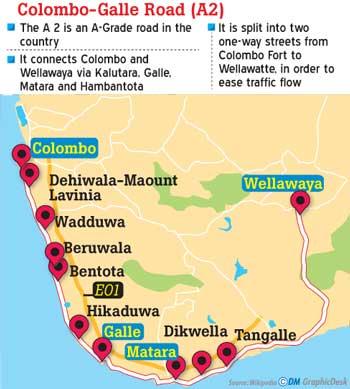

The Colombo-Galle Road, more popularly known as the Galle Road, begins at Fort and takes around four hours to complete. For the local and the foreigner alike, it’s arguably the most enriching stretch of land anyone can savour in Sri Lanka. It cuts through two provinces and three districts and forms one part of a bigger highway, the A2, which continues from Galle and passes through Weligama, Matara, and Hambantota, culminating in Wellawaya in the Moneragala district more than 110 kilometres from Tangalle.

The Colombo-Galle Road, more popularly known as the Galle Road, begins at Fort and takes around four hours to complete. For the local and the foreigner alike, it’s arguably the most enriching stretch of land anyone can savour in Sri Lanka. It cuts through two provinces and three districts and forms one part of a bigger highway, the A2, which continues from Galle and passes through Weligama, Matara, and Hambantota, culminating in Wellawaya in the Moneragala district more than 110 kilometres from Tangalle.

The Galle-Colombo section is one of the most frequented roadways in the country, and as of today continues to occupy a prominent place in Sri Lanka’s network of roads, byroads, and lanes, connecting the capital to a region which occupied a prominent place centuries ago. Due to urbanisation, however, it has been superseded by the sprawling E01 expressway, which locals and foreigners alike identify as the Southern Highway, or just the Highway.

That says a lot about the country’s roads. Today there are three types of highways as per the Road Development Authority: Class A (extending to more than 4,200 kilometres of land), Class B (more than 8,000 kilometres), and Class E (more than 215 kilometres). These can be distinguished from each another based on the locality and on whether there’s a toll charge (only on Class E, the “Highways” – Class A connects districts and Class B localities within districts). In that sense road tourism is not talked about, but it should be, and often it is. And the person doing the talking happens to be the tourist himself.

That says a lot about the country’s roads. Today there are three types of highways as per the Road Development Authority: Class A (extending to more than 4,200 kilometres of land), Class B (more than 8,000 kilometres), and Class E (more than 215 kilometres). These can be distinguished from each another based on the locality and on whether there’s a toll charge (only on Class E, the “Highways” – Class A connects districts and Class B localities within districts). In that sense road tourism is not talked about, but it should be, and often it is. And the person doing the talking happens to be the tourist himself.

Unlike the High Level Road and the Kandy Road, Galle Road enjoys a history dating back to before the time of the British, who constructed those first two roads in the interests of connecting the interior with the rest of the country. Historical sources tell us that from the 12th and 13th centuries AD the capital of the country began moving to the south-west, from dry country to wet country and then, with Kandy, to hill country.

The south remained a semi-autonomous province, ruled by either aspiring monarchs or loyal chiefs, and eventually it became a powerful centre of the kingdom: a refuge for rulers on the run and, from the 14th century AD onwards, the source of Sri Lanka’s most exquisite produce, including the most Sri Lankan of global exports, second only to tea, cinnamon – admired by administrators, travellers, princes, and poets.

The south remained a semi-autonomous province, ruled by either aspiring monarchs or loyal chiefs, and eventually it became a powerful centre of the kingdom: a refuge for rulers on the run and, from the 14th century AD onwards, the source of Sri Lanka’s most exquisite produce, including the most Sri Lankan of global exports, second only to tea, cinnamon – admired by administrators, travellers, princes, and poets.

Its place in contemporary Sri Lanka began to unravel with the arrival of the Portuguese and the Dutch, the latter of whom turned the region into cinnamon country. Travelling from Colombo wouldn’t have been an easy task for the administrator, but back then the most important port of call in the country was the Galle Harbour, and ships would disembark there; just a few hundred miles away from another important port, Godavaya, renowned in the eyes of the world from even before the 5th century AD.

During this period we hear of nobles currying favour with the Dutch, building bridges and making the road to Colombo more accessible. Typical of them is the story of Kuda Adikaram, a Minister in the court of the Kandyan king who defected to the Maritime Provinces (Dutch territory) and was baptised as Costa Lapnot; he was put in charge of the southern province, which he is said to have turned into a saltern and linked to Colombo via a network of canals, lagoons, and roads. If you pause at certain points in Galle Road today, you can find traces of these canals and spits: unused but eternal reminders of the past.

The British were road builders wherever they went and colonised, and they soon got down and began work on this stretch of land.

“The journey from Colombo to Galle,” wrote Ernst Haeckel, “is a favourite theme for a chapter in every account of a stay in Sri Lanka.” Emerson Tennent extolled “its peculiar style of beauty” which “nothing in the world can exceed in loveliness”: on one hand, there was “the range of purple hills, which form the mountain-zone of Kandy”, and on the other, “the blue sea, studded with rocky outlets”, rich in sunshine and verdure all year round. Roland Raven-Hart believed it to be the country’s first modern road: “so wide and smooth a road as in Europe in seldom to be found.” Bella Woolf, Leonard’s sister, observed that a trip “should not be missed”, right there in the first chapter of How to See Ceylon, Sri Lanka’s first pocket guidebook. Brohier, making that trip decades later, agreed: “idle moments will be filled with a wealth of interest.”

Much of the road’s charm lies in how different it is from other roads. It narrows and widens at alternating points, and one never misses the boutiques, the fish-vans, the restaurants, and of course the souvenir shops, right till the end. The Kandy Road is wide – too wide for me. By contrast, there’s something of the rustic and the familiar in Galle Road, no matter where you may be – from Moratuwa all the way through to Panadura, Kalutara, Beruwela, Alutgama, Bentota, Ambalangoda, Hikkaduwa, and the final point of call at “Point de Galle”.

To me it’s second only to taking the train to Badulla, but that’s the train, and you can’t pause where you want to on the ride. On Galle Road you can always pause: to savour the country, take photographs, visit a temple, and meet friends.

And there’s always something to buy: not just at the top end souvenir shops, but more importantly at the small time kiosk and boutique.

In that sense the Galle Road serves a function different to that of the Expressway. The E01 is for businessmen rather than tourists, when you think about it.

If it’s scenery you’re after, there’s another stakeholder you should fit in – the small time merchant who cannot thrive on the Expressway and whose business prospers on the coastal route. This is sustainable tourism.

What the Expressway lacks, the Galle Road has, and vice versa. One has temples and places of interest, the other does not; one takes you to your destination faster, the other does not; one has big restaurants, the other does not; one has sights, sounds, and sensations, the other does not. I can go on and on here, but you get the point: there’s always some merit in one road that’s lacking in the other.

As you travel through Panadura and Kalutara, and the road narrows down, only to suddenly open up when you least expect it, streets seem to take a life of their own, contributing to the character and the fabric of a locality. For sheer driving pleasure and touristic value then, nothing beats Galle Road – a point noted by visitors from afar, many a century ago. Even for local travellers, nothing can quite compare.