Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

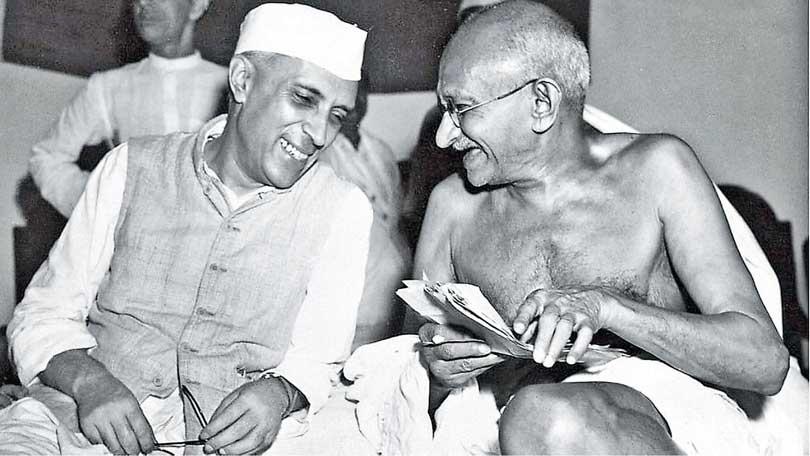

Buddhism had engaged two of the most charismatic leaders of India during its epic struggle for freedom, namely, Mahatma Gandhi and Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru. Both were emphatic about the great contribution that Buddhism had made to India’s ethos and their own personal world views. And yet, there were differences in what they looked at, or considered noteworthy, in Buddhism.

Buddhism had engaged two of the most charismatic leaders of India during its epic struggle for freedom, namely, Mahatma Gandhi and Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru. Both were emphatic about the great contribution that Buddhism had made to India’s ethos and their own personal world views. And yet, there were differences in what they looked at, or considered noteworthy, in Buddhism.

Gandhi, a deeply religious Hindu, saw Buddhism as a Hindu social reformist movement within the rubric of Hinduism. But Nehru, being a rationalist, refrained from linking Buddhism with Hinduism. He abhorred some de facto characteristics of Hinduism such as ritualism and caste and could not put Buddhism, which abhorred these institutions, within the rubric of Hinduism.

For Nehru, however, Buddhism was a standalone ideology, which was, at one and the same time spiritual and scientific. He considered this mix to be most suited to the needs of emerging India and the world at large.

For Nehru, however, Buddhism was a standalone ideology, which was, at one and the same time spiritual and scientific. He considered this mix to be most suited to the needs of emerging India and the world at large.

For Nehru, however, Buddhism was a standalone ideology, which was, at one and the same time spiritual and scientific

Gandhi’s Concerns

During his visit to Sri Lanka in 1927, Gandhi said: “I owe a great deal to the inspiration that I have derived from the life of the Enlightened One.” But he linked the Buddha’s teachings to Hinduism. In his book ‘Gandhiji in Ceylon’Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s Secretary, quotes his leader as saying that the Buddha was a “Hindu of Hindus”. In a speech at the Young Men’s Buddhist Association, Gandhi said: “He (Gautama) was saturated with the spirit of Hinduism, with the Vedic spirit.”

Gandhi went further to say: “And so far as I am aware, he (the Buddha) never rejected Hinduism or the message of the Vedas.What the Buddha did was to introduce a living reformation in the petrified faith that surrounded him.”

In a speech at the Buddhist College, Vidyodaya, in Colombo, Gandhi said: “By his immense sacrifice, by his great renunciation and the immaculate purity of his life, he left behind an indelible impress upon Hinduism. Hinduism owes an eternal gratitude to that great teacher.”

Gandhi went on to claim that the teachings of the Buddha found its full fruition in India. “It could not be otherwise, because the Buddha was saturated with the best that was in Hinduism, and he gave life to some of the teachings that were buried in the Vedas and which were overgrown with weeds.”

“His great Hindu spirit cut its way through the forest of words, meaningless words, which had overlaid the golden truth that was in the Vedas. He made some of the words in the Vedas yield a meaning to which the men of his generation were strangers.And he found in India, the most congenial soil.”

According to Gandhi, the Buddha gave Hinduism “a new life and a new interpretation”. The Buddha’s teaching was” all expanding and all embracing, which made it survive his own body and sweep across the face of the earth.”

“I claim that this achievement is a triumph of Hinduism,” Gandhi declared.

In Gandhi’s view, the Buddha did not reject God. “It seems to me confusion has arisen over his rejection of all the base things that passed in his generation under the name of God. His whole soul rose in mighty indignation against the belief that a being called God required for his satisfaction the living blood of animals in order that he might be pleased -- animals which were his own creation. He therefore reinstated God in the right place and dethroned the usurper who for the time being seemed to occupy that White Throne. He emphasized and re-declared the eternal and unalterable existence of the moral government of this universe. He unhesitatingly said that the Law was God himself,” Gandhi said.

Nehru’s Buddhist Leanings

India’s first Prime Minister Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru was a rationalist and yet he was deeply influenced by the Buddha. He named his daughter Indira Priyadashini, because “Priyadarshi” was the name adopted by the great Buddhist Emperor Ashoka after he became a Buddhist prince of peace. Nehru was instrumental in making the Ashoka Chakra India’s symbol. Nehru’s attachment to the Buddha was both intellectual and sentimental. He would visit the Samadhi Statue of the Buddha at Anuradhapura whenever he went to Sri Lanka. He visited the Buddhist country in 1931, 1939, 1954, 1957 and 1962.

As a man who kept urging the superstitious and ritualistic Indians to cultivate a “scientific temper” Nehru was naturally attracted by the rationalism propounded by Buddha. “The Buddha asked no man to believe in anything except what could be proved by experiment and trial. All he wanted men to do was to seek the truth and not accept anything on the word of another even though it be of Buddha himself. That seems to me the essence of his message,” Nehru said.

Going further, the Indian leader said: “The Buddha had the courage to attack popular religion, superstition, ceremonial, and priest-craft, and all the vested interests that clung to them. He condemned also the metaphysical and theological outlook, miracles, revelations, and dealings with the super-natural. His appeal was to logic, reason, and experience; his emphasis was on ethics, and his method was one of psychological analysis, a psychology without a soul. His whole approach comes like the breath of the fresh wind from the mountains after the stale air of metaphysical speculation.”

“Buddha did not attack caste directly, yet in his own order he did not recognize it, and there is no doubt that his whole attitude and activity weakened the caste system.”

Nehru’s belief that social change can be brought about only by the broadest social consensus stemmed from the influence of the Buddha, Ashoka and Gandhi

Application of Buddha’s Teachings

The influence of the Buddha showed in Nehru’s foreign policy. The policy was motivated by a yearning for peace, international harmony, and mutual respect. It aimed at resolution of conflicts by peaceful methods. On November 28, 1956, Nehru said, “It is essentially through the message of Buddha that we can look at our problems in the right perspective and draw back from conflict and from competing with one another in the realm of conflict, violence and hatred.”

Nehru’ s concept of the ‘Panchsheel (Pancha Sheela) and ‘Non-Alignment’ stemmed from Buddhism. Nehru told the International Buddhist Cultural Conference, at Sanchi on November 29, 1952: “The message that Buddha gave 2,500 years ago shed its light not only on India or Asia but the whole world. The question that inevitably suggests itself is, how far can the great message of the Buddha apply to the present day world? Perhaps, it may, perhaps it may not; but I do know that if we follow the principles enunciated by Buddha, we will win peace and tranquility for the world.”

On October 3, 1960, Nehru told the UN General Assembly: “In ages long past a great son of India, the Buddha, said that the only real victory was one in which all were equally victorious and there was defeat for no one. In the world today that is the only practical victory; any other way will lead to disaster.”

Nehru tried his best to apply Buddha’s teachings in running India’s domestic affairs. His belief that social change can be brought about only by the broadest social consensus stemmed from the influence of the Buddha, Ashoka and Gandhi.

In his Independence Day speech on August 15, 1956 Nehru said: “One feels proud that the soil on which we have been born has produced great souls like Gautama Buddha and Gandhiji. Let us refresh our memories once again and pay homage to Gautama Buddha and Gandhiji and great souls like them who have molded this country. Let us follow the path shown by them with strength and determination and cooperation.”