Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Why do some people fear or dislike refugees? Why are they xenophobic? Isn’t harbouring ill-feelings towards fellow human beings inhuman, especially at a time when they are in misery and going through hardships?

Why do some people fear or dislike refugees? Why are they xenophobic? Isn’t harbouring ill-feelings towards fellow human beings inhuman, especially at a time when they are in misery and going through hardships?

These questions loom large against the backdrop of rising xenophobia in Europe and the United States, and revelations this week by the United Nations that the earth is at present carrying the recorded history’s biggest refugee population – 65 million. The shocking figure includes 41 million internally displaced people due to wars and conflicts but excludes 19 million people displaced by natural disasters. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees is unable to cope with the rising refugee numbers while relief organisations are overwhelmed. With many affluent nations, towards which thousands of refugees continue their march, closing their borders and taking other measures to stem the flow, the UN now seeks to turn its annual General Assembly sessions in September into a world refugee summit.

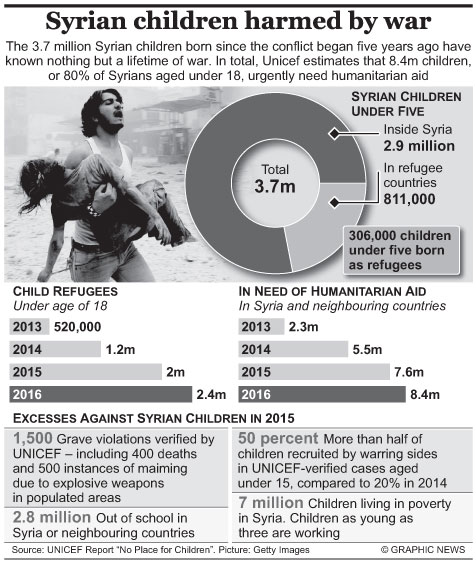

The refugees on the run include those fleeing the wars in Syria and Iraq and the conflicts in Afghanistan, South Sudan, Nigeria, Libya and Somalia. Not to mention nearly two million Palestinian refugees who have been languishing in refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank for the past 70 years or so. This week, Iraq’s war against the terror group ISIS in Fallujah and Mosul created more than 100,000 displaced people.

On Saturday, during a visit to Lesbos, the Greek island where thousands of asylum seekers arrive before they struggle towards affluent European nations, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon denounced “border closures, barriers and bigotry”. He implored European leaders to stop treating refugees as criminals and start the process to resettle more refugees.

Pope Francis in a prophetic plea last week said, “We are bombarded by so many images that we see pain, but do not touch it; we hear weeping, but do not comfort it; we see thirst but do not satisfy it. All those human lives turn into one more news story. While the headlines may change, the pain, the hunger and the thirst remain.”

As hostility toward migrants and refugees surges in Western countries, the European Union has shown signs of fracturing over the refugee influx, with the issue taking centre stage during debates that took place in the run up to yesterday’s British referendum where voters decided whether to remain in the EU or leave.

Why cannot countries open their borders and welcome refugees? After all, they are fellow members of the human race. When there are no racial, cultural or linguistic barriers to love or sex between two human beings, what prevents us from achieving the unity of mankind?

Sociologists may come up with several theories to answer questions on xenophobia, but the search for the unity of mankind remains elusive. Former United States President Bill Clinton told a US talk show in 2014 that an alien invasion “may be the only way to unite this increasingly divided world of ours”. But the answer lies not in an external threat but within us. We need to break artificial political and cultural barriers – and move towards the world order that existed prior to the 19th century nation-state, before which no visa was required to travel from country to country.

The concept of nation-states, perhaps the root cause of present day xenophobia over refugees, took root in Europe as a response to the uneasiness of accommodating diversity. So they combined the cultural boundaries of a ‘nation’ with the political boundaries of a ‘state’ to create what came to be known in political jargon as the nation-state.

Though post-World War II Europe has made strides towards liberal values, it has not completely freed itself from the yoke of the nation-state. Whatever took place in terms of accommodation of “migrants” apparently was largely due to economic factors. The first influx of migrants was the army of cheap labour: In Germany, the Turks -- and in Britain, France, the Netherlands and other European countries the people from their former colonies in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

Yesterday’s referendum in Britain was perhaps a move towards returning to the nation-state shell, with warts and all. It appears that a sense of panic over a refugee invasion – some identify it as Islamophobia or the fear of Islam -- has beset a majority of the people in the US and Europe. Their fear of fellow human beings has reached such ridiculous proportions that it has become easy for hate-mongering politicians to rise to the threshold of power. In the US, it is Donald Trump. In Britain, it is the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), in Germany, it is Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West); in Austria, the Freedom Party; and in France, the National Front led by Marine Le Pen, who faced hate speech charges last year after she compared Muslims praying in the streets to the Nazi occupation.

Little do they realise or acknowledge that the past and present actions and policies of the US and Europe have led to the crises that have driven millions of people out of their homes and villages. The US, European nations and their oil rich Arab allies were responsible for the wars in Iraq, Syria, Libya and elsewhere.

Yet these countries are not in the least bothered about the plight of the refugees. The closest US shore is more than a safe distance away across the vast Atlantic Ocean. Saudi Arabia and other affluent Arab states won’t open their doors to refugees fully, while, ironically, fleeing Syrians and Iraqis see the Islamophobic West as a far better refuge than Islamic Arabia.

The US has the power to end these wars and bring peace that will in turn bring the refugees home. If not self or selfish reasons, what is preventing this great nation from doing so?

If the countries that have the power to end wars do not use that power to do so, they not only renounce their responsibility as civilised nations but also become accomplices in the crime of creating refugees – the crime of heaping misery upon misery on a people who, just the day before the war started, had everything in life.

The Syrian refugee fleeing the conflict had a home of his own, a family, a job and access to health services and other basic necessities. His children went to school and had a dream of becoming scientists, doctors, judges and journalists.

But, alas, when the war broke out and bombs and missiles destroyed neighbourhood after neighbourhood, his family escaped to Turkey, where he paid all his life’s saving to people smugglers to undertake the dangerous journey in a rubber dinghy to reach the Greek island of Lesbos across the Mediterranean Sea that has become a watery grave for thousands of people, including the four-year-old Aylan Khurdi. His children have no school to go now. But he now learns from the UN report that about 100,000 children who are in search of a safe haven in Europe have no parents or are separated from their parents. Reports say an increasing number of children are sexually abused by predators and paedophiles in refugee camps. All that the refugee wants is a place to start life anew. Certainly the misery-driven refugee is not a missionary with a mission to Islamise Europe.