Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

The National Movement for Social Justice recently published a set of proposals for the ongoing Constitutional Reforms. The Daily Mirror published the part I of this article on Monday, January 3 and following is Part II.

The National Movement for Social Justice recently published a set of proposals for the ongoing Constitutional Reforms. The Daily Mirror published the part I of this article on Monday, January 3 and following is Part II.

Establishing a Select Committee on Electoral Reforms by the Parliament of Sri Lanka in April 2021 is a welcome step. The Parliament appointed such a committee previously in 2003. It is noteworthy that Minister Dinesh Gunawardena, who was the Chairman of the House at that time, is also the Chairperson of the present Committee. As stated in the Interim Committee Report 2003, it aimed to find solutions to the following issues.

The main reason for violence-and over-spending is the elevated level of competitiveness among the candidates within the existing “proportional representation electoral system with open lists and preferential voting.” Competitiveness among candidates from the same party is particularly detrimental to the health of the political party system.

The main reason for violence-and over-spending is the elevated level of competitiveness among the candidates within the existing “proportional representation electoral system with open lists and preferential voting.” Competitiveness among candidates from the same party is particularly detrimental to the health of the political party system.

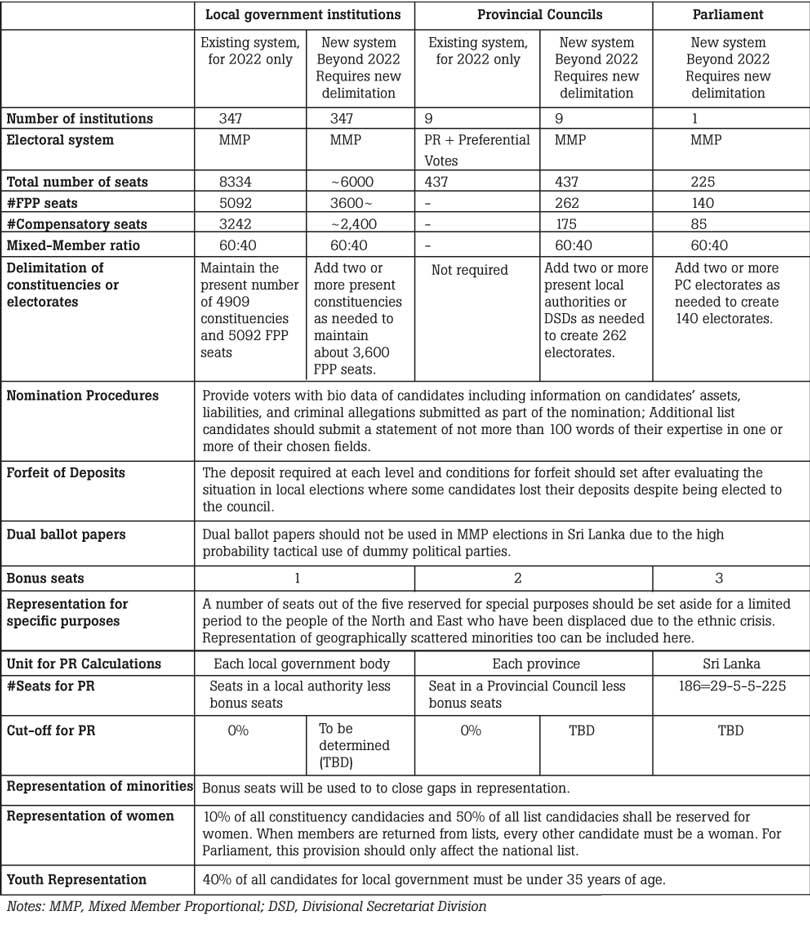

The idea of a mixed-member system as a solution has been on the agenda since 2003. In a typical mixed-member system, 60% or so of the total number of members are elected in ‘first-pass-the-post’ or FPP, contests from smaller constituencies or electorates.

One major concern about the mixed-member system is the fact that communities of interest, whether ethnic, religious, or ideological, have little chance of winning these FPP seats. In response there are arguments for maintaining the present PR system but taking steps to change the behavior of candidates, make electoral districts smaller, or devise numerous ways of assigning smaller areas of responsibility to elected members. We address these issues in the main document, but the focus of this report is on making the mixed-member systems more effective and equitable.

According to The Local Government Elections Amendment Act No, 1 of 2016, 10% of all constituency: candidates and 50% of the additional candidates must be women. While we endorse that mandate, we do not endorse the mandate the total of percent of women members in a council must be 25%

NMSJ devoted two or more of our weekly Kathikava series or public discussions on current topics to the topic of electoral reforms. We also held several roundtable discussions with key stakeholders. Our aim is to initiate an electoral reform process that is informed by evidence. Towards that end, we summarize the salient issues under four principles of electoral reforms: (1) A positive change in the political culture (2) Independent and transparent electoral processes (3) Democratic representation, and (4) the Ability of the winning Party to govern.

The specifics of the proposals made here need further analysis and simulations using data from past elections. We urge the Select Committee to solicit such an analysis prior to making a final recommendation to the Parliament.

A positive change in the political culture: The electoral system should help move the country’s political culture in a positive direction. Some of the necessary steps are to (1) Enforce election spending restrictions; (2) Provide voters with biographical data on the Internet, including details of candidates’ education, careers, assets and liabilities, and information on criminal charges against them; (3; Allow by-election provisions to prevent violations of election laws; (4) Set minimum criteria for the internal democracy of political parties and” (S) Maintain no more than the minimum number of representatives required.

Independent and Transparent Electoral Processes: Essential elements of an electoral process - from Delimitations as needed; Setting of election dates, especially for local government and provincial council elections, on a fixed schedule; Acceptance of nominations; to the Release of results, should be governed by an independent Election Commission. All appointments to the Elections Commission and other Commission relevant to the elections must be made in a manner that ensures their independence.

Fairness in Representation: In addition to providing proportional or approximate proportional representation to participating political parties, the electoral system should be designed to ensure that the aspirations of the country’s minorities, whether ethnic, religious, or ideological, are represented.

The Ability of the Winning Party to Govern: There is general agreement that an electoral system should enable a simple majority for the winning party. The mode to achieve this is to award a limited number of bonus seats to the winning Party, as has been the practice in Sri Lanka for decades, or promote a culture of consensus politics overall. Distorting the proportional electoral system or dependence on a superpower president are not in accordance with the representative democracy that we aim to achieve through elections.

The issues pertaining to the four objectives will be detailed in the main document. We conclude this summary with an initial set of proposals for electoral reforms for all three levels of government, preceded by a rationale for our proposals.

Variants of our initial proposal are open for discussion. However, we wish to emphasize that whatever variant that is adopted must provide a proportional result based on the four principles of elections for a just society. In addition, we recommend that the mix ratio in a mixed- member method should be maintained at 60:40. Considering the few countries around the world where there is a mixed proportional representation system. We note that the percentage of FPP seats is typically kept at a maximum of 60% as a way of optimizing the need for a representative responsible for a small electorate arid ensuring proportionality in the result.

According to the report of the Local Government Electoral System Review Committee of the State, the Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government to increase in the number of seats in local government system from the previous 4386 to 8719, and the fact that the ‘winning’ party did not get a majority of seats in the councils have been identified as the main issues of the mixed member proportional system used in that election. The increase in the number of seats is indeed would create an issue. But the argument that a Party that wins most seats FPP with whatever percentage of votes should receive a majority of seats in a council is erroneous.

In the 2018 local government election, the Sri Lanka People’s Front (SLPP) polled 44.65% of the vote, while the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party polled 8.94% and 4.44% respectively, island wide. The total percentage of votes received by these three parties/alliances adds up to 58.03% of the votes. Since these three Parties formerly contested election under the banner of UPFA, the reason SLPP, the party with the most votes, was not able to gain a majority of seats in the local councils is more likely to do with political divisions than the electoral system. It is unfortunate that a committee appointed by a Ministry endorsed a common misperception among the public and even the stakeholders in interpreting the results of a mixed- member proportional system instead of educating them.

We do not endorse the Committee’s proposals to change the mixed-member ratio to 70:30 or compensate for overhangs seats of the winning Party, by reducing share of seats of other Parties to ensure a majority for the winning Party, because such measures distort proportional representation vastly. However, we endorse the proposal to award bonus seats to the winning Party since it is a more open and transparent solution which has been in practice in Sri Lanka for decades. The additional proposal to mandate the return of a minority candidate through those bonus seats if minorities are not represented in the winning Party, is also a valuable proposal.

Doubling of the number of seats in local government bodies in the 2018 election is a genuine problem. But the root of the problem is the setting of the number of wards for the local government system at 4919 and the number of councilors to be returned by FPP at 5092 including members from multi-member wards by the 2014 Delimitation Committee. There is no clear rationale for deciding on these numbers except presumably for the need to enable the 4365 incumbent councilors at that time to return through FPP contests in the new system. Since the Local Government Elections Act No. 22 of 2012 which was valid at that time stipulated that the additional number of Members to be returned by Party lists will be limited to 30% of the number of FPP members, the total number of councilors was limited to 6623.

The Local Government Elections Amendment Act No. 1 of 2016 enacted by the Yahapalana government .established in 2015 changed the mixed-member ratio to 60:40 for an effective change in the number of additional seats to 67% of the FPP seats. They further changed the electoral method from a Mixed-Member Majoritarian (MMM) method adopted in the 2012 legislation to a mixed-member proportional (MMP) method. Although this was a progressive step, it increased the total number of seats to 8334. The government .should have decided on the minimum number of seats that local government bodies would need for its functioning and set the number of wards required accordingly. It is unfortunate that even the civil society at that time did not raise a voice about the increase in the number of seats.

It is doubtful whether a delimitation of a smaller set of wards are possible before the local government elections which are due shortly after February 2022. The following proposals are for long term reforms (or reforms beyond 2022). A table of proposals that follow give scenarios both short-term and long-term is given at the end.

Give full powers to the Election Commission to conduct local government and provincial council elections on a pre-determined schedule

The elections for the nine Provincial Councils were held intermittently from 2012-2014. Their terms have now expired, and new elections have been delayed for two to four years. The terms for Local Councils too expire in February 2022.

As a matter of urgency, we urge the Committee to give full powers to the Election Commission to independently set a schedule for calling for nominations and holding elections for the nine provincial Councils on the same date. The date for elections to the local government too should be announced to allow these institutions to function without undue breaks.

The Commission should also have the power to use the same methodology used for the last held election if Parliament fails to pass or complete the relevant ordinances.

The need for a comprehensive electoral analysis with simulations

The 2018 Local Government Elections is an important event in that it was the first time that a mixed-member proportional (MMP) representation system was implemented in Sri Lanka or anywhere in Asia. It is unfortunate that our Election Commission has not been able to make the election data available in an analyzable form.

It is essential that the Select Committee solicits and receives a thorough analysis of past election results with simulations before finalizing recommendations for an MMP system for the three levels of government.

A proposal for long-term electoral reform

1. Local Government

1.1. The Election Commission shall hold elections for all local governments at the same time every four years according to pre-defined schedule.

1.2. Determine the optimum number of constituencies or wards required for local councils after a study of political representation needed for an effective functioning of a council and its various committees, and the area and the population of each local government body. For argument’s sake, we set the number of wards at 3,000 or about 4.7 GNDs per ward on average.

1.3. Delimit 3,000 or so new local government wards by combining two or more of the existing 4092 wards as needed.

1.4. If any overhangs result after an election, create extra seats in a council to accommodate those. The number of overhang seats in the 2018 local government election was 385 or only 5% of the total 8334 seats. This is not a substantial number we feel.

1.5. The party with the highest number of seats wins one bonus seat. The number of bonus seats can be revised to a number commensurate with the total number of members in a Council.

1.6.Representaiton of Minorities: If there is a minority of 10% or more in a local government authority and there is no minority representation among the elected or selected members from the party with the highest number of seats, the bonus seat received by that Party must be allocated to a minority candidate.

1.7. Representation of Women: According to The Local Government Elections Amendment Act No, 1 of 2016, 10% of all constituency: candidates and 50% of the additional candidates must be women. While we endorse that mandate, we do not endorse the mandate the total of percent of women members in a council must be 25%. It would be more practical to mandate, for example, that one out of every three members returned in total by any party must be a woman.

1.8. Youth Representation: 40% of the total candidates in each party should be youth under 35 years of age.

1.9. Online Tool for Submitting Nominations: The Election Commission should set up an online tool to calculate the percentage of women and youth quotas in any nomination submission and flag any errors. In addition, every political party or independent group must have the opportunity to correct any errors in the nominations three days before the closing date.

2. Provincial Councils

2.1. The elections for the nine provincial councils shall be held by the Election Commission on the same day every five years according to a schedule established by Election Commission.

2.2. The current total number of 437 members for the nine Provincial Councils shall remain the same, 60% of the number or 262 members shall be elected FPP from that may provincial Constituencies and another 175 members shall be selected from Party Lists for a mixed-Member ratio of 60:40.

2.3. The boundaries of 262 constituencies shall be demarcated by combining existing local government jurisdictions and/or Divisional Secretariat Divisions.

2.4. The party with the most seats should receive two bonus seats. After a study, the number of bonus seats can be revised to be proportional to the total number of members in the House.

2.5. The proposals for local government regarding overhangs (1.5), minorities (1.6), women’s representation (1.7), and the provisions on a flexible nomination process (1.9) also apply to provincial councils. Youth Representation Provision (1.8) do not apply to

Provincial Councils.

3. Parliament

3.1. Elections shall be held as per a schedule set by the election commission according to provisions in the Constitution unless dissolved before that date as allowed in the Constitution.

3.2. The total number of members of Parliament shall be maintained at 225. Of those, 140 shall be elected FPP from a set of constituencies numbering the same and the other 85 from additional candidate lists.

3.3. The winning party gets five bonus seats. Five more seats will be reserved for special cases including displaced voters. Another 29 seats will be reserved for National List seats, for a total of 39 reserved seats. If there are overhangs those will be awarded from the National List allocation, and the remainder distributed among qualifying parties proportionate to the share of votes received nationality.

3.4. The remaining 186 seats shall be divided proportionately among the political parties, using an appropriate cut-off. First, the 140 candidates who have won in FPP contests from the 140 constituencies shall be returned. The remaining 46 additional seats shall be divided among the districts in proportion to the number of votes each party received from each district.

3.5. The proposals for local government regarding overhangs (1.5), minorities (1.6), women’s representation (1.7), and the provisions on a flexible nomination process (1.9), except the youth Representation Provision (1.8), shall apply to the Parliament.

3.6. The specifications in this proposal are for initial discussions only. For example, here we propose that 39 of the 225 seats in Parliament should be reserved for specific purposes – i.e. 5 bonus seats, 5 seats for displaced persons and unrepresented minorities, and 29 National List seats, and the remaining 186 seats to be divided proportionately at the national level among qualifying parties. The cut-off for qualifying should be fair to smaller parties. (Of the Parties represented in the 2020 Parliament the lowest percentage of national votes received by any Party is 0.3%). Secondly, choosing the right balance between representation and stability is a political decision, buy a full analysis using simulations of past election result is needed before reaching such a decision.

This article was compiled by the writer for the National Movement for Social Justice (NMSJ) on November 1, 2021