Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

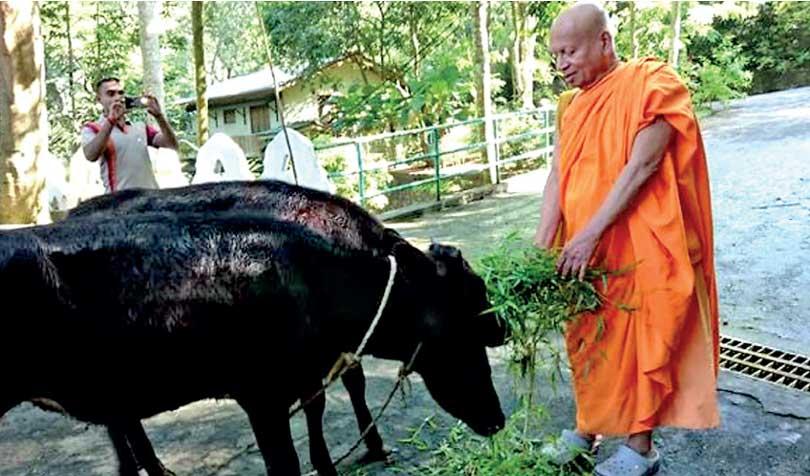

A Buddhist monk feeds a cow released from a slaughter house

A Buddhist monk feeds a cow released from a slaughter house

The Sri Lankan government is to enact an integrated law banning cow slaughter. The government is portraying the ban as an economic and development-oriented measure to enhance domestic production of milk and secure greater income for the farmer

The Sri Lankan government is to enact an integrated law banning cow slaughter. The government is portraying the ban as an economic and development-oriented measure to enhance domestic production of milk and secure greater income for the farmer

There are strong arguments against the theory that a ban on cow slaughter will yield economic benefits. If there is a ban what will farmers do with cows which have ceased to yield milk? What will they do with bulls which cannot be put to use? According to Dr.Chandre Dharmawardana, Sri Lanka does not have enough pasture land and water to have a successful dairying sector which can obviate milk imports. If cattle cannot be killed, beef cannot be exported. To meet the needs of the Christian and Muslim minorities, beef will be imported, government says. But imported beef will certainly be too costly for the common man.

Be that as it may, the unstated reasons for the ban seem to be cultural, semi-religious and political. That begs the question as to whether the cow is venerated in Sinhala-Buddhism as it is in Hinduism. James Stewart, in his paper Cow Protection in Sinhala Buddhist Sri Lanka (2013), points out that while it will be incorrect to say that Sinhala Buddhists “venerate” the cow in the same manner as Hindus in India do, it cannot be denied that Sinhala Buddhists have a “high opinion” of cattle. They make special efforts to protect cattle. Many, if not all, abjure beef.

Be that as it may, the unstated reasons for the ban seem to be cultural, semi-religious and political. That begs the question as to whether the cow is venerated in Sinhala-Buddhism as it is in Hinduism. James Stewart, in his paper Cow Protection in Sinhala Buddhist Sri Lanka (2013), points out that while it will be incorrect to say that Sinhala Buddhists “venerate” the cow in the same manner as Hindus in India do, it cannot be denied that Sinhala Buddhists have a “high opinion” of cattle. They make special efforts to protect cattle. Many, if not all, abjure beef.

Stewart points out that ardent votaries of cow slaughter ban refer to the Suttanipāta in which the Buddha is reported to have condemned the ritual slaughter of cows by Kings. “Not by their feet, nor by their horns, nor by anything else had the cows harmed (anyone). They were like sheep, meek, giving pails of milk. (Nevertheless) the king, seizing them by the horns, had them killed with a knife,” the Buddha observed.

However, Stewart notes that allusions to cow slaughter in the Buddhist canon are “extremely rare”. It is “entirely swamped by repeated assertions that all sentient beings everywhere should be treated with loving-kindness and nonviolence.” In other words, Buddhism gives no special place or shows no special favor, to the cow. For Hindu Indians, on the other hand, the cow is “the” holy animal.

However, the Sinhala-Buddhist and Indian Hindu attitudes to the cow have a similar origin. And they have had a similar trajectory too, Stewart says. Both in India and Sri Lanka, cow protectionism had not been part of their religions in their earliest days. According to historian Dwijendra Narain Jha (The Myth of the Holy Cow 2001) , there was no injunction against cow killing in ancient times and that cow ‘worship’ with an injunction against its slaughter, came later in order to distinguish Hindus from people of other faiths or outsiders. Similarly, in Sinhala-Buddhism, cow protectionism or the abjuration of beef have no scriptural sanction (expect when taken as part of a moral duty to be kind to animals in general).

As in India, in Sri Lanka, sensitivity about the life of a cow emerged when the time came to distinguish Sinhala-Buddhists from the Portuguese, the Dutch, the British and followers of Abrahamic religions Christianity and Islam. Furthermore, what began as a cultural marker and divider gradually took on a political character when groups had to be formed for the pursuit of political power. It was in this phase, that cow protectionism took on an aggressive character showing intolerance, marginalization and violence.

The 1893 anti-Muslim riots in the Indian pilgrimage centers of Benaras and Hardwar began as a protest against cow slaughter by Muslims. When Mahatma Gandhi found that the cow slaughter issue was preventing Hindus and Muslims from uniting against the British, he made a fervent appeal to the Muslims to voluntarily give up cow slaughter. Earlier, the Moghul Emperor Akbar had banned cow slaughter in certain parts of his empire for the sake of peace among his subjects.

In Sri Lanka too, cow protection became an issue in the context of the influx of people from Europe, Stewart says. Robert Knox, who was a prisoner of the king of Kandy in the late 1600s, found that many Kandyans were disdainful of captive Europeans, whom they referred to pejoratively as ‘beef eating slaves’. Stewart reports that even today a pejorative dietary label is applied to non-Sinhalas, especially the Muslims.

Writing in one of the Sri Lankan dailies, Aryadasa Ratnasinghe says that when the Portuguese became a power in Sri Lanka in the 16th.Century, and Buddhism declined as a result, beef eating became acceptable. But opposition to it arose with the advent of the Sinhala-Buddhist revivalist movement in the last part of the 19 th.Century under the leadership of Anagarika Dharmapala. Dharmapala went from place to place in his vehicle, displaying a banner which read Gawa mas nokanu (Don’t eat beef).

Eventually, Dharmapala’s anti-cow slaughter movement faded, but only to be revived in the 2000s when radical Buddhist groups like the Bodu Bala Sena and the Sinhala Ravaya took it up as part of their campaign against “Muslim cultural separatism”. Cow protection was added to the anti-Halal certification and anti-Burqa campaigns. In 2013, a 30 year old Buddhist monk, Bowatte Indraratna Thera, committed self-immolation in front of the Dalada Maligawa in Kandy.

Stewart quotes Shriya Rathnakāra’s work, Give Us Space to Live, to say that Buddhist doctrine urges animal non-killing and vegetarianism. Rathnakāra employs the Mettasutta to press his case. Bhikkhu Hivipāṇo, in his book The Question of Vegetarianism, promotes non-killing of any animal, not only the cow. But still, the cow gets the prime place in animal welfare campaigns in Sri Lanka. The “Organization for the Preservation of Life” used cow protectionism to make its case popular. This is because the cow is “adored” if not worshiped, by Sinhala Buddhists. That is for the milk it gives. Milk is seen as the source of life, and the cow is equated with the life giving and loving “mother”. In support, Stewart points to the veneration of Kiri Amma.

“The Organization for the Preservation Life carries a piece of advertising that prominently utilizes an image of Śhiva, Parvātī, and Kāma Dhenu—the latter, of course, being a precursor deity to Kiri Ammā. A billboard of the organization carries a picture of a cow with a caption asking “How can we eat this?” On the Facebook page of the Gawa mas nokanu community, there is a picture of a teary-eyed, terror-stricken cow in an abattoir with a caption asking “Are we the only ones who fear death?”

Stewart’s case is that the “key motive behind cow protectionism in the Sinhala animal welfare movement is rather more concerned with establishing a Buddhist identity that is constitutive of non-violence and animal protectionism. This is conveniently represented through the symbol of the cow—a creature which is passive, nurturing, harmless, and so on.”

This is true of cow protectionism in India too. And in both countries, it has been coopted to meet ethnic, religious and political ends. Cow protection movements in Hindu India and Sinhala Buddhist Sri Lanka help establish the contention that Hinduism and Buddhism are non-violent religions that allow cows to flourish in contrast to others.

But the difference between the Indian and Sri Lankan case is that unlike in the Indian case, cow protection does not stand alone in Sri Lanka. It is part of the larger animal welfare movement, though primacy is given to cow protection. And the animal welfare movement, in turn, is deemed to be synonymous with Sinhala Buddhist nationalism that powers much of Sri Lankan politics.