Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

| It would be politically suicidal for any leader or the government to make a genuine effort to find out what happened to the missing persons |

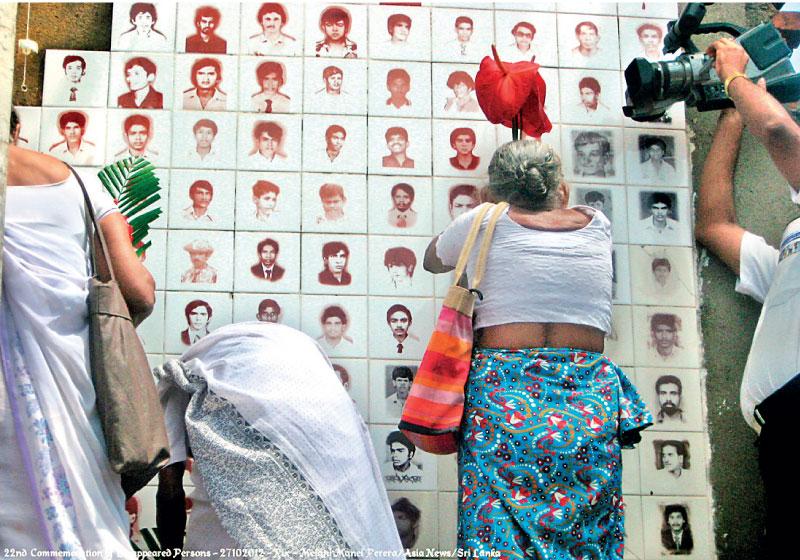

Media reported that the Office on the Missing Persons (OMP) is to resolve the issue of people who had disappeared during the war between the armed forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) within the next six months.

Media reported that the Office on the Missing Persons (OMP) is to resolve the issue of people who had disappeared during the war between the armed forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) within the next six months.

The Chairman of the OMP Attorney-at-Law Mahesh Katulanda during a press conference on Wednesday at the Department of Government Information said that the OMP had fast-tracked the mechanism for tracking missing persons and that the process is being carried out transparently.

The preliminary investigations of the first phase of tracking will be completed by December after which certificates of absence or death certificates in the name of disappeared persons will be issued to their relatives, according to the OMP Chairman.

Special facilities for the close relatives of the missing persons will be provided with parents of missing persons who are on the waiting lists for kidney or heart surgeries at government hospitals being treated as special cases, with the intervention of the OMP.

Similarly, according to Katulanda, children in such families will be directed to appropriate institutions for them to obtain further education or to develop their skills to engage in self-employment.

In spite of individuals of all three communities involved in the southern and northeastern insurgencies and the police as well as security forces personnel having disappeared during armed clashes in the past four decades, only the relatives and the political parties of those who have gone missing in the north and the east have been seeking justice for the victims.

They have been launching various struggles such as demonstrations and fasts while making representations to international human rights organisations including the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). The struggles launched in the 1980s and 1990s by the relatives of victims in the southern parts of the country faded away before the end of the separatist war.

The OMP was instituted under a special law adopted during the Yahapalana Government in 2016 primarily in accordance with Sri Lanka’s undertakings to the UNHRC to trace the victims of disappearances - or enforced disappearance as they are being called lately - and to meet justice to them or their relatives.

However, OMP seems not to trace the victims alive now or it doesn’t seem to believe that any victim is alive somewhere, as it is more inclined to issue certificate of absence or death certificates for the victims.

The relatives of the victims who, on the other hand, have rejected earlier moves by the authorities to issue these certificates, have been demanding the authorities reveal what happened to their loved ones and reveal where they are if they are still alive.

The authorities have so far failed to address these concerns and in fact, it is highly unlikely that even the OMP is capable of answering these questions with respect to at least one missing person. This disagreement between the relatives of victims as well as the Tamil politicians and the authorities including the OMP is a vivid sign that the problem of enforced disappearances would last for at least another decade.

A pertinent question that arises with the latest announcement by the OMP head is what prompted him to make it at this moment. If he is confident that OMP would trace the victims which might be numbering about 20,000 within the next six months or that the relatives of the victims would agree to receive the certificates of absence or death certificates during the same period it would be a great achievement that has to be announced to the people, as it would mark the resolution of one festering problem in the country.

However, the Opposition parties, as in the case of the current controversy over the government’s professed move to fully implement the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, might view this announcement as an inducement on the part of the government to the Tamil political parties to get their support at the next Presidential election at which President Ranil Wickremesinghe is said to be a main contender.

However, as in the case of the controversy over the 13th Amendment, the possibility of Tamil leaders not accepting this formula of issuing certificates without knowing what happened to the victims is very high.

Similarly, the Tamil leaders might view the announcement by the OMP chief as a message to the UNHRC which would hold its 54th Regular Session between September 11 and October 13 in Geneva where Sri Lanka’s human rights record would be taken up for discussion. It is a well-known fact that the Sri Lankan government on the eve of every Regular Session of the World’s human rights body has been doing something to convince Geneva that it is serious in the matter of human rights.

However, it would be difficult for the government - irrespective of which party is in power – to convince the world that the OMP would not meet the same fate that the numerous commissions appointed by several past governments with the professed objective of resolving the missing persons’ issue.

The first such commission was appointed in 1992 by President R. Premadasa whose regime was accused of thousands of disappearances. Later President Chandrika Kumaratunga appointed a national-level commission as well as three zonal commissions for the same purpose.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa whose regime was also accused of a large number of disappearances during the war on his part appointed the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) in 2010 and the Paranagama Commission which was also called the missing persons commission in 2013. It must be noted that the Paranagama Commission had received over 19,000 complaints.

All these commissions as well as the OMP were appointed to ward off international pressure over the human rights situation in the country. And reports of all these commissions went missing without tracing a single person who had disappeared, for obvious reasons.

Probably only a few people - some the close relatives of victims - might believe that anyone who had gone mission is still alive as their hearts always resist the belief that their loved ones are no more. On the other hand, it was only President Gotabaya Rajapaksa among all leaders of the country since the 1980s was blunt in saying that all those who had disappeared were “actually dead,” during a meeting with the UN Resident Coordinator Hanna Singer on January 17, 2020.

It would be politically suicidal for any leader or the government to make a genuine effort to find out what happened to the missing persons. On the other hand, it would similarly be suicidal for the Tamil leaders to accept this reality and adjust their demands accordingly. So the debate goes on unabated.