Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

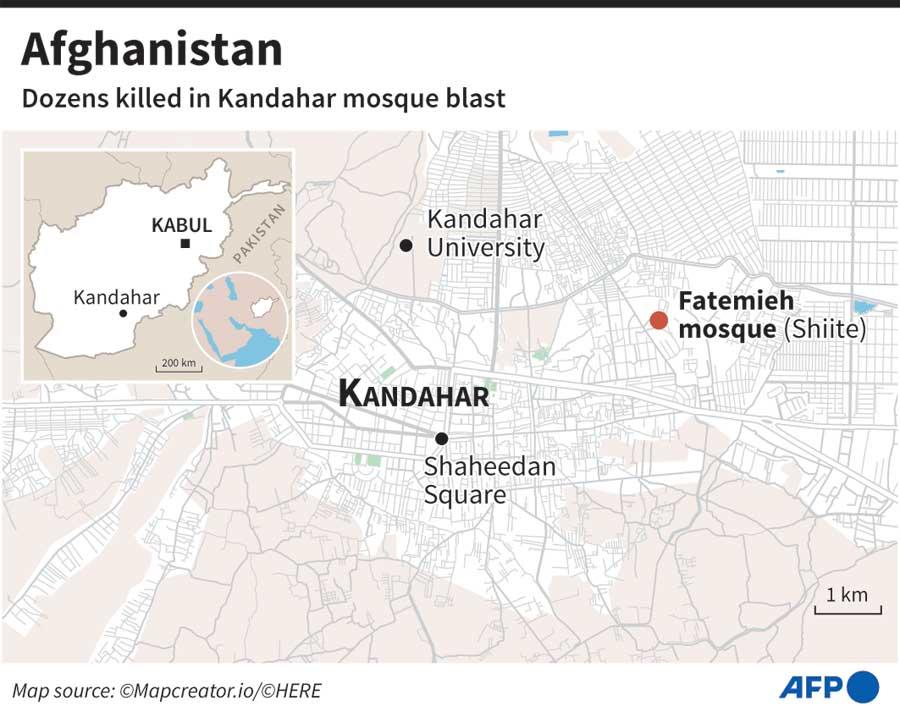

The blast in the Shiite mosque in Kandahar last Friday comes exactly a week after a similar blast at a Shiite mosque in the northern city of Kunduz

Last Friday’s suicide bomb blast in the Taliban stronghold of Kandahar was the second such attack on a Shiite mosque in as many weeks since the Taliban took over Afghanistan following the August-end withdrawal of the United States-led occupation forces.

mosque in as many weeks since the Taliban took over Afghanistan following the August-end withdrawal of the United States-led occupation forces.

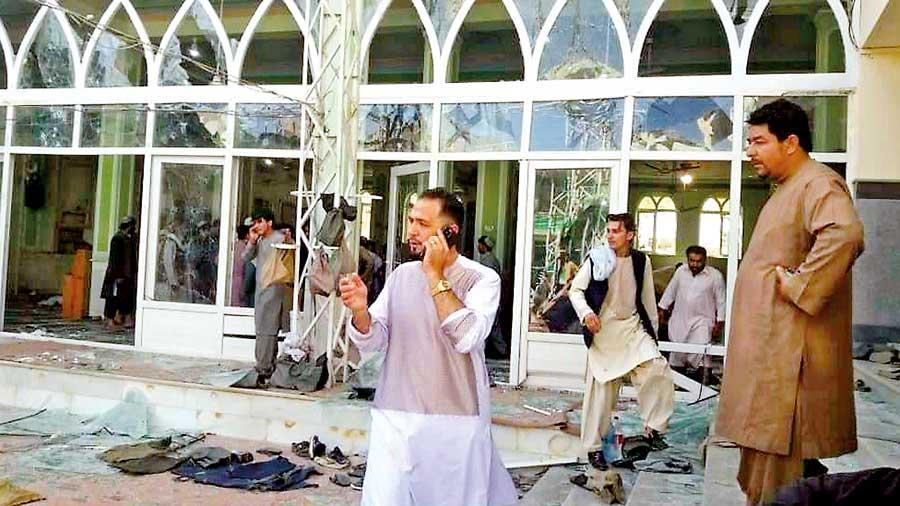

The suicide bombers killed 47 worshippers and wounded more than 70 during prayers on Friday, the most sacred day of the week for Muslims. The attack came a week after a similar blast killed about 45 Shiite Muslim worshippers, also during Friday prayers, in the northern city of Kunduz.

The responsibility for the first attack was claimed by the Islamic State Khorasan (IS-K), a new variant of the ISIS which is lying low in Iraq and Syria after a series of military defeats and the death of its leader Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. The IS-K is also believed to have carried out the second attack.

These attacks cast doubts about the new Taliban rulers’ ability to restore order in the country and honour their pledge to the US in terms of the Doha agreement. A key condition of the agreement was that the Taliban would take steps to prevent terror groups from using Afghanistan as a base. Since the Taliban seized full control of the country, the IS-K has proved it can strike at will at any target. Prior to the Taliban takeover, the IS-K and the Taliban had clashed with each other on a limited scale. But after the takeover, the Taliban seem to have deferred attempts to take on the IS-K due to its preoccupation with matters concerning governance and efforts to sort out internal squabbling. Or the Taliban may have reached some kind of understanding with the IS-K to turn a blind eye to its rival’s terror attacks as long as the targets are the Shiite Muslims.

This is because the Taliban leadership is seen to be anti-Shiite. The Taliban’s antagonism towards the Shiites is rooted in two main causes. One is Wahhabism’s influence on the Taliban leadership, and the other is the contempt a majority of Pashtuns, Afghanistan’s largest ethnic group, harbor against the Shiite Hazaras who constitute about 15 percent of the Afghan population. Throughout Afghanistan’s history, the Hazaras, believed to be the descendants of the Mongols, have remained a persecuted minority. They had come under attack from the Taliban and al-Qaeda even during the US occupation of Afghanistan.

While the Pashtuns’ persecution of the Hazara Shiites is largely linked to power politics, Sunni Islamic extremists – be they the Taliban, al Qaeda, ISIS or IS-K – go after them because in Wahhabi teachings the Shiites are considered non-Muslims. Wahhabism, an extreme form of Sunni Islam, has two manifestations – political Wahhabism and doctrinal Wahhabism – and they operate in isolation and in tandem. Saudi Arabia, the fountainhead of Wahhabism, spread this hardline version of Islam at the behest of Western powers during the Cold War and even after its demise. In Saudi Arabia, political Wahhabism is represented by the Royal family and the doctrinal Wahhabism by Saudi theologians. However, the power of Wahhabi theologians has been eroding in relation to Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman’s modernization programme.

To delve deeper into the schism within Islam, its origins need to be explained.

No sooner the Prophet Muhammad passed away than the edifice of Islam suffered major cracks. In the ensuing dispute over leadership, one section of the community backed the Prophet’s bosom friend Abu Bakr to be the caliph while the other promoted the Prophet’s son-in-law, Ali. Though Abu Bakr was elected as Islam’s first caliph with Ali himself pledging allegiance, the bickering laid the foundation for a civil war that saw the assassination of the third caliph, Osman, and inter-Muslim wars when Ali, who was married to the Prophet’s fourth daughter Fatima, was eventually elected as the fourth caliph. A few years later, Ali was also assassinated. The final break-up took place when Ali’s son and the Prophet’s grandson, Hussein, and his unarmed followers were massacred by a tyrant who was ruling the Islamic world from Damascus. Those who supported Ali eventually came to be known as the Shiites, while those who bowed to the Damascus power centre came to be known as Sunnis.

Five centuries later and after many doctrinal differences, in the aftermath of the Mongol invasion of the Middle East, there emerged Sunni Islam imams such as Ibn Taymiyyah who declared the Shiites as non-Muslims. Although Ibn Taymiyyah was imprisoned and he died in jail, his writings influenced latter day imams such as Abdul Wahhab, the founder of Wahhabism, and Syed Qutb, a leader of the pan-Islamic Brotherhood movement. These imams were regarded as the fathers of radical Islam, which was further distorted by the likes of al-Qaeda and the ISIS. This explains why the Sunni Islamic extremists like ISIS and IS-K kill Shiites.

Although Wahhabi theologians have branded the Shiites as non-Muslims, political Wahhabis had no qualms over embracing Iran, when the pro-American Shah was ruling the world’s largest Shiite Islamic country.

The Shiite Iran became an adversary of political Wahhabis only after the 1979 Islamic revolution. In neighbouring Iraq, there had been hardly any Sunni-Shiite conflict until the Saddam Hussein regime was overthrown by the invading US-led forces. In Iraq, prior to the US occupation, the Sunnis and the Shiites lived in harmony, intermarried and had few if any dogmatic issues. The children of Sunni-Shiite mix marriages called themselves Sushi. But sectarianism rose its ugly head in Iraq under the watch of US and British forces with many Iraqis believing that the chief architects of sectarian bloodshed were the US and British intelligence.

The US war on terror in Afghanistan and Iraq also coincided with the rise of Iran as a regional power. This gave security headaches to Saudi Arabia, its Arab allies and Israel. They feared a Shiite crescent spreading from Iran across Iraq, Syria and South Lebanon where the powerful Shiite militia group Hezbollah holds sway. Adding to their Shiite-phobia is the Yemen war, with Houthi rebels who are largely Shiites emerging as a formidable force. In the Sunni-Shiite politico-ideological war, millions of dollars are spent on propaganda and on mercenary imams who from pulpits decry their opponents, instead of building peace based on many common grounds between the two factiosn.

Sadly, efforts aimed at peace between the two mainstream divisions of Islam have not succeeded due to bigotry on both sides. Of the two, the Sunni extremism is the bigger obstacle to peace. They would not even mind big powers and Zionist Israel exploiting the division to achieve their sinister goals in the Middle East.

In Afghanistan, the economically deprived Shiite Hazaras have become more vulnerable after the Taliban takeover. The world community which is mounting pressure on the Taliban to help women and girls to win their rights, also should step up efforts to protect minorities such as the Shiites of Afghanistan.