Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

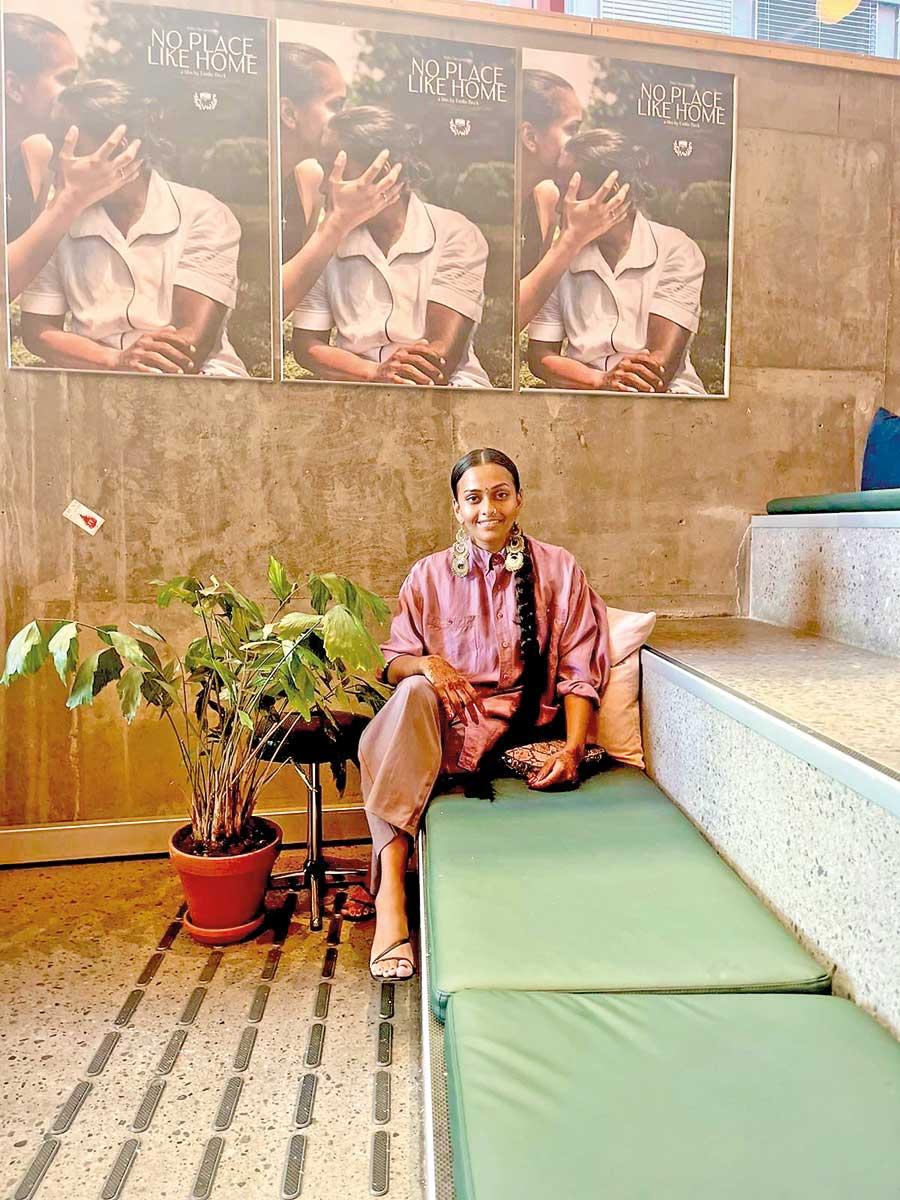

Embracing with love - Priyangika with her biological mother

- Adoption cannot and should not be a solution for poverty says Priyangika Samanthie

- I didn’t grow up as a European and then got interested in Sri Lankan culture as most diaspora kids around me have

- The love and connection with a mother doesn’t focus on poverty or privilege

- My adoptive parents always raised me to know that I would one day find my way back home

Priyangika Samanthie was another ‘brown child from abroad’ when she landed in Norway, seven weeks after she was born. Even though many Sri Lankans thought that she grew up white for a better opportunity, she was searching for her roots since her childhood. Her adoption was based on false documents following which she lodged a complaint at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). Investigations are still underway. In a recent Al Jazeera documentary titled ‘No Place Like Home’ Priyangika confronts the painful secrets of international adoptions.

grew up white for a better opportunity, she was searching for her roots since her childhood. Her adoption was based on false documents following which she lodged a complaint at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). Investigations are still underway. In a recent Al Jazeera documentary titled ‘No Place Like Home’ Priyangika confronts the painful secrets of international adoptions.

In an exclusive interview with the Daily Mirror, she revealed the difficulties she experienced as an adopted child, loopholes in her adoption process, baby boxes and illegal adoptions that need to stop right away.

Excerpts :

Q How was it like growing up in Norway?

Q How was it like growing up in Norway?

The first thought that came to mind was ‘lonely’. Incredibly lonely. Even though I grew up in a household that tried their best to acknowledge my fundamental needs in life — I felt as though my nature was different from my circumstances. I grew up in a small town. My adoptive brother Prishantha and I were one of the first brown children. I remember feeling as if I was a statue when people crossed us. As children, we had big curls and hair and people used to touch our hair and skin. I remember experiencing angry stares, but I couldn’t understand what was going on. Later in life my Norwegian family members told us about the difficult experiences of the surroundings. One day, our adoptive grandmother had walked with me in my stroller and experienced that someone questioned why her son had gotten “one of those”. One of those brown children from abroad.

I didn’t grow up as a European and then got interested in Sri Lankan culture as most diaspora kids around me have. I grew up spending time with their family members. It wasn’t until Tamil families started to migrate to our small town in the Midwest in Norway that I felt a sense of belonging. I spent lots of time on a family friend Archie Amma’s lap who was telling me about Sri Lanka and fairytales in Tamil. It was a mix between Tamil and our hearts connected. As a child and as a human, I seek a community; a belonging deeper than luxury. Love has always triumphed over luxury. It was the love and care that my adoptive parents put into learning about Sri Lankan food culture and culture, connecting us with the Tamil families and attending cultural events, that made me feel a sense of belonging. Whilst most Sri Lankans I meet think that I’ve focused on my opportunities to better my life in Europe, my only focus as a child and adult was to deepen my roots. I went to the school library as a child to try to find books to study Sinhala and would have tantrums when they didn’t understand what I meant. Before I graduated secondary school, my librarian showed me that she had found a book about Sri Lankan birds for me. For the first time, I felt seen for my Sri Lankan identity except for my family. It’s been incredibly hard to explain my focus on Sri Lankan people because they thought I grew up white as a better opportunity, but my only dream was to grow up like them; even if that meant that I had to suffer. Later on in life, my adoptive family told me that I would have had a better childhood if I grew up with my Sri Lankan family. “You might suffer, but you would’ve been able to breathe the same air as amma and we know that it would’ve been enough for you”, I have heard from Norwegian family members.

Q Since when did you start looking for answers regarding your adoption?

I think it already started on the plane to Norway. After breastfeeding me for seven weeks, Amma was suddenly gone. My Norwegian parents said that I reacted to the formula they gave me, but kept crying and searched for the breast. It’s been an ongoing joke around me my whole life that “She cried on the way from Sri Lanka till Norway, and never stopped crying”. Which I think is actually true in my case. My soul has been grieving my whole life. The love and connection with a mother doesn’t focus on poverty or privilege. I could feel her feelings on my skin and when I spent time with her later in life, it felt as if I could finally be in my body without a storm within. In kindergarten I used to refuse to come home with my Norwegian parents because I noticed that other children had parents whom looked like them. I was constantly waiting for Amma. I had continuously stated since then that I was kidnapped and wasn’t meant to be in Norway. My Norwegian family and their community tried their best to calm me down, but nothing worked.

I was five when the Norwegian family started to prepare me for a reunification or deportation. We spoke about the pros and cons of finding amma. I realised early that they didn’t have the talk with Prishantha. They handled my feelings completely differently and for that, I’ll always have my deepest respect for them as humans. I searched for answers while he became silent. I think that’s what has been the greatest challenge with our adoptions, that most people forget that our bodies cry for our fundamental needs even if our circumstances become more ideal. Would it have been more ideal for me to be in survival mode with my family? Everything within me screams yes.

As a seven year old, I knocked on my adoptive fathers door and wondered if he could help me write letters to the government, adoption agency and orphanage for answers to find Amma. This was the start of twelve longyears of searching. My adoptive parents always raised me to know that I would one day find my way back home. Even if I couldn’t find my relatives. I think it’s the main reason why I’ve seen myself as a foster child and not as an adoptee. In the documentary “No Place Like Home” Prishantha states that he was never scared that I would find answers, he was more scared if I didn’t. It wasn’t until fall 2013 that a group of Muslim men in Sri Lanka found her. I never thought I would see the day of light with her when they found her. I had recently become a mother to my eldest son Nishantha and my only wish was for him to have his Archie. To sit on the lap and get the same stories as I did. In high school, I had some Buddhist and catholic men searching for me. They went to the greatest length and travelled over the island (for free) to find answers. Most of them have become my lifelong friends back home. Whilst searching, then came across concepts such as baby farms but they also discovered that my documents were falsified. I remember one of them calling me and saying “It seems as though you never left”. I did not understand what he meant, until he explained that my court document of adoption and passport were fake. My whole world fell apart — because it confirmed my instincts, I wasn’t meant to be adopted.

Amma and I met at IndependenceSquare on Independence Day in 2014. We attended Good Morning Sri Lanka later the same day. It wasn’t until I was in the recording studio that I realised that the men wanted me to do an interview. Suddenly our faces were on the main newspapers in the country. People in the street showed their love and support. Men would whistleblow to me and ask me if they could trade places. It was a rollercoaster and the reunion turned into everything else than I had imagined. I wanted us to have a mother-daughter relationship, but she was full of grief and anger. She kept apologising for losing me. It wasn’t until I moved to Sri Lanka in 2015 that she told me that I wasn’t meant to be adopted. In the beginning of recording “No Place Like Home”, she told us untold stories that she hadn’t shared with anyone. It wasn’t poverty that made her seek alternative care, it was the connection from family members on half of my family side to the underworld. She wanted to protect us which is why she wanted us to move into the home together. The Salvation Army worker who had told her about the alternative of care, had shared that we would live in an NGO-house together. In the documentary, Amma kept stating that she went back to search after losing me. While I listened to her stories and calculated the years, I realised that we were searching for each other at the same time. I went back to my school diary and read about mutual experiences in similar time periods. I told her that I used to look at the moon and say goodnight every night, because at least we stared at the same moon. She answered “I found comfort knowing that the moon would raise you”.

The director chose to leave out the kidnapping story from the hospital, Salvation Army workers purposely misleading and the corruption in our case. The story is twisted because it would be too comfortable and challenging to watch, she thought. The consequence is that the audience is confused but the comment section on Al Jazeera witness’s YouTube channel has reduced amma to be a useless poor person which is nothing like the woman I have known her to be.

Q In the recent Al Jazeera documentary, your Norwegian parents claim that they were paid extra to shorten their stay in the country. Could you tell us how the adoption took place?

My Norwegian parents were in Sri Lanka for five weeks to complete a court case for the adoption. Their lawyer had offered to shorten the case by paying a bribe. They had refused to take the offer, but when I asked them why they did not change the lawyer, they have been honest about mainly focusing on their own wish. It seems to be that they deep within knew that it was a possibility that it could’ve been a corrupt case, but not in their wildest dreams do I think they realised that it was a kangaroo court. After almost twenty years of research on the adoption fraud, I have experienced that Norwegian parents heard about the corruption to other countries while going through the same channels. I have also experienced having to share with the adoptees and adopters that the translation was purposely misleading. In our case, they reacted strongly to the courts mistreating Amma. After being reunited, she could confirm that she was told a completely different story in court than what took place. She was told that we would live in the NGO-couples house and whilst she built up our life, she would receive 1Lk to figure our situation out in the early 90s. After a couple of years, we could return home. In reality, they fled the country after the court case.

Q How was it dealing with Lankan authorities during the process? Were they helpful and what were the challenges?

I have always been warmly welcomed in Sri Lanka by the population, it has however not been the same experience with the authorities. In our case, the orphanage has been the most untruthful and difficult, but I learnt early that there was no such thing as getting help from the authorities. Until I met my lawyer and went to CID to file a complaint.

CID started the process of following up the trace of my illegal adoption. I have yet to receive an update on the investigation. My lawyer and I hope to connect thousands of more cases to the investigation in the future.

Q Some authorities including the hospital have been maintaining manual records that were eventually destroyed. What are your comments regarding such lapses in the system?

I wasted years of search based on finding basic information because the hospital has not digitised the information. It would be a lot easier to confirm the information if the books or information were not destroyed. The only solution to this now, to be able to reunite potential kidnapping cases and in reunions would be a DNA-system. Over the years of research many adoptees and researchers have experienced that hospital workers were a part of the adoption fraud.

“I wanted us to have a mother-daughter relationship, but she was full of grief and anger. She kept apologising for losing me. It wasn’t until I moved to Sri Lanka in 2015 that she told me that I wasn’t meant to be adopted”

- Priyangika Samanthie

Priyangika running a campaign against illegal adoptions during the ‘Aragalaya’

Q Sri Lanka has certain laws for adopting. The eligibility criteria are different when it comes to foreign parents. Are you aware of these criteria? What other changes/ reforms are required in the adoption process?

The investigation of inter country adoption to foreign countries has proved that the third parties in an adoption process opens up for an illegal market of children. Even if the laws and regulations seem to regulate the market, it keeps it well alive. There are no reforms that can regulate the market overseas. The only solution to end trafficking is to stop with the financial costs in adoption and rather focus on it as alternative care for families.

As long as the international market is overseas and has interpretation, it won’t be possible to regulate adoptees wellbeing and human rights. Laws and regulations seem to be symbolic in the adoption market from Sri Lanka. The law specifies that the receiving country must send reports of the child, but there’s not enough capacity to ensure this. What if it doesn’t? Should the child be sent back? Who should pay for this? Isn’t it possible to falsify these reports? The check-ups done by social workers in Sri Lanka can always be improved, but the focus should be there, to strengthen and improve the system on the island; not to repress the island by continuing the neo-colonial market of children overseas. The consequences of losing one’s cultural and identity of origin has major consequences for adoptees. Only a very small percentage of children seem to achieve the aim of an adoption — to create stability for the child. Most of the foreign parents lack the cultural background, knowledge and equipment to raise a foreign child.

As the consequence, the European parents raise them as white Europeans which reduces their origin to only becoming a skin colour. A skin colour most of them grow up hating because of the amount of racism they experience. Research underscores that adoptees are twice as likely to need mental health treatment compared to biological children living with their family of origin. After 11,000 illegal adoptions from Sri Lanka through brokers and concepts such as baby farms, the authorities should not allow children to be sent abroad. By law, poverty is not seen as a valid reason alone for adoption yet Sri Lanka seems to use it as a solution instead of fixing the problem. Adoptees and diaspora must therefore use our positions to put pressure on the reforms. For as long as the market involves financial compensation it should be seen as trafficking and not as an alternative to have children. Even though many families on the island need an alternative care — it should be focused on finding and creating alternatives on the island. This is one of the main reasons why my team and I recently started Roots Search Center. We will set up family programmes to strengthen one parent households to achieve the stability within. If it’s not possible, we can ensure to be a support system for the family after the child has been given to alternative care.

It’s easier for authorities within the country to regulate families even if it’s not as much of a priority as it should be. If anything happens to the child while being overseas it’ll

be under another authorities’ responsibility and the Sri Lankan authorities will not be informed. Norway has experienced two of the main racist murders in the country on two adoptees. Their countries and family of origin are unaware.

Q There was a time when Sri Lankan parents gave away their children to foreigners due to poverty. Do you think this is still happening in rural areas of Sri Lanka?

Unfortunately we experience that this is still happening and with concepts such as baby boxes, the authorities try to fix an issue that is deeper with temporary solutions. No one seems to think how it’ll influence the child to learn that they were left in a box at the hospital. That the concept violates every single act of their fundamental human rights to know about their origin. In the worst cases, it can have a medical consequence to not know about one’s medical history.

It’s mind blowing to me that instead of implementing free medical abortion, sexual education to learn about protection, parenting programmes, financial support for families by the government with extra support for one parent households and tries to improve the shame culture for victims of rape or children upside marriage, the authorities rather implement a baby box as a solution to shame-culture. I constantly handle cases of the children from baby farms or “door-step” cases through kidnapping and the victims are heavily affected by their birth stories. Too many of them have chosen to commit suicide after learning that they were found and saw themselves as unloveable. No one seems to think about how the victims of baby boxes will be affected. I receive requests from domestic adoptions in Sri Lanka who have found out that they were adopted as an adult. It has heavily affected their lives and I see similarities within their struggles with foreign adoptees. Adoption cannot and should not be a solution for poverty. As mentioned, it’s legally not a valid reason alone. Most of the parents from rural areas have shared that they would be willing to handle the stigmatization and upbringing of a child if they had financial support; to end the issue, the authorities must focus on strengthening families. The other options will eventually end up with mass lawsuits against the government.

Q Following your investigation have there been any positive outcomes/ responses with regards to the inter-country adoption process in Sri Lanka?

I have received tons of messages on social media and feedback from authorities, both in Sri lankan and globally, that the focus on the adoption market has taught them the downside of it as well. It has been a romanticised alternative to have a family, but also purely been seen as a great solution for children’s current situation. The feedback has been that they are reconsidering adoption and rather would like to find other solutions to help families. Either strengthen them or become a foster parent.

Q What’s your message to parents willing to give their children for adoption?

If adoption is mainly a solution to stigmatization and financial difficulties, I suggest contacting NGOs for family support before seeking a permanent solution. However, if the situation is unbearable and alternative care is a must, make sure to go through proper channels with a trustworthy lawyer to create solid documentation of the domestic adoption. Ensure that you get separate copies and insight of the follow up reports. It’s important to state that the adoption is permanent and you would give up your connection/contact to be the guardian of the child, so be sure that you’re willing to accept this sacrifice.

After the adoption, seek professional help to get support for the mental toll that this sacrifice has had on you. Just because you had to give up your child does not make you less of a parent and parents who’s in the separation of a child are allowed to acknowledge their grief as well. Roots search center can provide mental health programs if needed.

It’s important to remember that a financial crisis and the current state of the country leaves families in desperate positions. It’s crucial to not accept a growing market which takes advantage of this. If anyone witnesses concepts such as collecting centres, baby boxes, trafficking on Facebook marketplace etc, it’s important to take action. Children and families should receive support without being a victim of crimes.

Priyangika Samanthie