Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

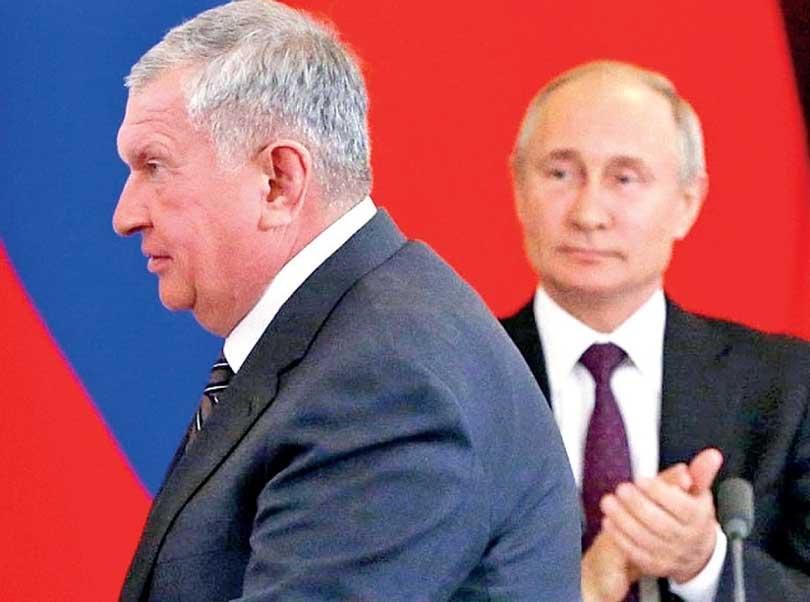

Putin applauds oligarch Igor Sechin

Putin applauds oligarch Igor Sechin

The US and its Western allies have sanctioned top Russian businessmen dubbed ‘oligarchs’ as part of their campaign against Russian President Vladimir Putin. On March 3, the White House, in coordination with Allies and partners, targeted additional Russian elites and family members who continued supporting Putin “despite his brutal invasion of Ukraine”.

The US and its Western allies have sanctioned top Russian businessmen dubbed ‘oligarchs’ as part of their campaign against Russian President Vladimir Putin. On March 3, the White House, in coordination with Allies and partners, targeted additional Russian elites and family members who continued supporting Putin “despite his brutal invasion of Ukraine”.

The White House charged that “these individuals have enriched themselves at the expense of the Russian people, and some have elevated their family members into high-ranking positions. Others sit atop Russia’s largest companies and are responsible for providing the resources necessary to support Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. These individuals and their family members will be cut off from the US financial system, their assets in the United States will be frozen and their property will be blocked from use.”

There are five reasons for the US action against the oligarchs: 1. The oligarchs are the pillars of the hated Putin regime 2. Much of the post-USSR Russian economy is in their hands 3. Crippling them will weaken the Russian economy 4. Their ultimate obliteration will lead to Western and US businesses taking over their businesses under a friendlier post-Putin regime 5. Lastly, the Russian masses, impoverished by the ugly politico-economic regime of the oligarchs, will welcome the new pro-Western politico-economic order.

There are five reasons for the US action against the oligarchs: 1. The oligarchs are the pillars of the hated Putin regime 2. Much of the post-USSR Russian economy is in their hands 3. Crippling them will weaken the Russian economy 4. Their ultimate obliteration will lead to Western and US businesses taking over their businesses under a friendlier post-Putin regime 5. Lastly, the Russian masses, impoverished by the ugly politico-economic regime of the oligarchs, will welcome the new pro-Western politico-economic order.

Origin of the Oligarchs

Russian oligarchy has its origin in Mikhail Gorbachev’s“Glasnost” (Openness) and “Perestroika” (Restructuring) reforms in the 1980s. Perestroika entailed the logic of economic markets and the ending of central planning characteristic of the Soviet regime. In the domestic sphere, the concept of private property was introduced, and in the international sphere, the Soviet economy was integrated with the capitalist global market.

Writing in www.wsws.org in 2018, Clara Weiss says that in 1982, the Soviet Communist Party set up mechanisms to work out ways to set up capitalism. In this endeavour, the party had the full support of the Soviet bureaucracy and the trade union leadership. Most significantly, the privatisation project also was fully backed by the US Establishment.

The Soviet economy, “which had been built with tremendous sacrifices by the working class over decades, was sold for peanuts to former Red Directors, rising stars of the gangster-elite and Western hedge funds,” Weiss points out. “The most famous case was that of Boris Jordan, also called the ‘Russian Czar’. Jordan, a young hedge fund manager from Boston with Russian ancestors, acquired 17 million of the 144 million vouchers distributed to Russians for use in bidding for shares in the privatised companies and, on this basis, bought stakes in many of Russia’s most important companies.”

Weiss alleges that the US was hand-in-glove with Soviet politicians and the bureaucracy in implementing Perestroika in order to secure the interests of the US bourgeoisie. The main front organisation for the State Department and CIA was the AFL-CIO. “Starting in 1988, the AFL-CIO provided a substantial amount of funding for the NPG (Independent Miners’ Union), as well as other so-called independent trade unions that supported the Yeltsin faction in the power struggle in Moscow against the faction around Gorbachev,” Weiss writes.

From the very beginning, the US, through the AFL-CIO, as well as the bureaucracy, sought to subordinate NPG’s leadership to their interests. Several trade unionists from the workers’ councils active in the miners’ strike were invited to the US, where they met representatives from the State Department and the AFL-CIO, Weiss adds.

One of the biggest acts of looting of state property was undertaken by the so-called independent union federation, the FNPR, Weiss says. In September 1992, a contract between the FNPR and the government formally established the transfer of the whole property of the Soviet unions to the FNPR. Weiss quotes a 2009 article in Nezavisimaya Gazeta, to say that the property transferred included 100,000 pioneer camps, over 25,000 sports facilities, around 1,000 sanatorium complexes and 23,000 clubs and culture palaces. Some estimates put the total worth of the property transferred at about US$100 billion.

Another huge source of profit for the FNPR became the lending of its real estate to companies and banks. According to the Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Mikhail Shmakov, the head of the FNPR since 1993 and a close ally of Vladimir Putin, was considered to be one of the richest men in Russia. Weiss quotes a Russian sociologist who said: “A minister became the holder of controlling shares in a concern; an administrative head in the Ministry of Finance became the president of a commercial bank; a senior manager in Gossnam (the former Soviet agency responsible for distributing the ‘means of production’ became the chief executive of the stock exchange.”

Only a tiny oligarchy and a very small upper middle class have benefited from Perestroika. The Credit Suisse global wealth report for 2016 revealed that among all major economies, Russia had by far the highest concentration of wealth in the hands of an oligarchy. The top decile owned a stunning 89% of all household wealth in Russia, compared to 78% in the US and 73 in China. 122,000 individuals from Russia belonged to the world’s wealthiest 1%, and the country had 79,000 dollar millionaires. Russia also had the world’s third-largest number of billionaires, 96, topped only by the 244 living in China (which had almost 10 times the population of Russia) and the 544 billionaires in the US. Only about 4% of the population qualified as “middle class.”

By contrast, (according to Nezavisimaya Gazeta) in April 2017, some 56% of Russian workers made less than 31,000 rubles (US$531) a month. The official subsistence level was later lowered by the government to less than 9,691 rubles (US$166), a wage that is impossible to live on. Official statistics indicated that the number of extremely poor people, living beneath this low threshold, stood at around 19 million.

According to the Russian journal Expert, the total industrial production in Russia collapsed by 55% in the 1990s thanks to Perestroika. By comparison, during the Great Depression in the US, production declined by 30%. In Russian history, only the combined effect of World War I and the Civil War after the October Revolution had been worse. Foreign capital flowed to the stock markets and financial institutions, but not into industry.

Coal-mining employment in Russia plunged from 900,000 to roughly half of that by 2000. Production, which had peaked in 1988 with 400 million tons, dropped to just 225 million in 1997. In 1998, after the closure of at least 58 mines, the government announced plans to shut down another 86 out of the remaining 200 coal mines. Every year, an estimated 15,000 workers died in workplace accidents, according to numbers of the International Labour Organisation. A horrifying 190,000 workers died annually as a result of exposure to dangerous conditions at work.

Workers were going without wages for months and even years. While this was a general phenomenon in the Russia of the 1990s, the situation was particularly dire in the coal industry, a key Russian industry. Dozens of Kuzbass mine managers were assassinated as part of the mafia wars in the 1990s. The Kuzbass had the third-highest murder rate in the nation. One mine director, who was asked by the Moscow Times about the influence of organised crime on the coal business, answered briskly: “They don’t influence it. They run it.”

The West is getting ready to exploit the situation. The ongoing fight against the Russian invasion of Ukraine is not to save Ukraine but to rid Russia of its indigenous oligarchs, who are the main support base of the ultra-nationalistic Putin, who is challenging the West’s hegemony in Europe. But that is not all. The ultimate goal is to replace the indigenous Russian oligarchs with Western or West-backed entrepreneurs. The expectation is that the long-suffering Russian worker will welcome such an intervention as a god-send and a harbinger of a better life under Western-style capitalism.