Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

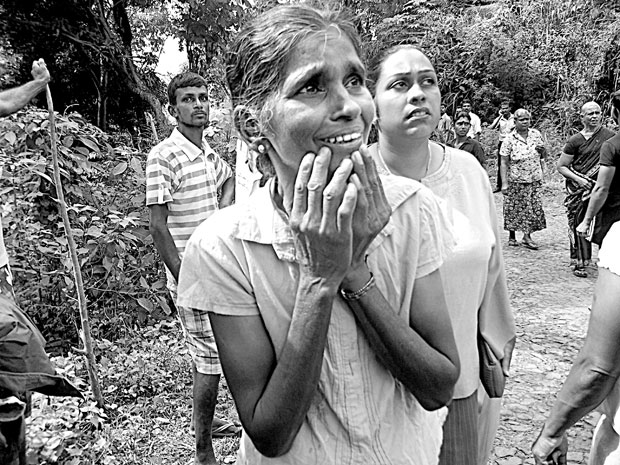

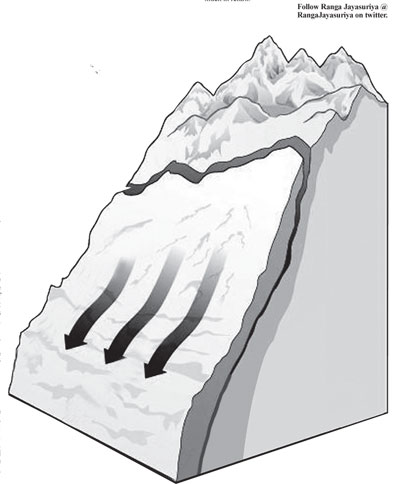

A deadly landslide that swept through the Meeriyabedda tea plantation in Koslanda last week, buried an unknown number of plantation workers and their families under a mound of mud, wiping out an entire village.

A deadly landslide that swept through the Meeriyabedda tea plantation in Koslanda last week, buried an unknown number of plantation workers and their families under a mound of mud, wiping out an entire village.

About a hundred people, many of whom were estate Tamils are feared dead in the worst natural disaster to hit Sri Lanka since the 2004 tsunami. Nonetheless, the government, which habitually declares days of mourning over the passing away of aging monks and octogenarian politicians, has not thought it fit to do so for the deceased workers, who live in abject poverty. This could well be an indication of how much the lives of average citizens are worth (in this case, the most vulnerable as well) on the scale of the government’s value system.

Estate Tamils of Indian Origin have long been the victims of the antipathy of successive governments. They were demeaned by the per-independence Sinhala and Tamil political leaderships and were disenfranchised by independent Ceylon’s first Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake. Later, in 1977, J.R. Jayawardene restored the citizenship rights of a large swathe of estate Tamils. However, pre-independence antipathy gave into a general sense of apathy for the next few decades. Estate Tamils lived segregated lives, mired in inter-generational poverty, in their hill country ghettos.

Sri Lankan mainstream politics was taking a racist a caste conscious bent even before independence. Those who drafted the Donoughmore Commission Report, granting universal franchise to the citizens of then Ceylon -- the first non-white British colony to have full voting rights -- were well aware of those inclinations of the local political elite.

In the Commission report, Lord Donoughmore recommended that five years of residency (including temporary absence not exceeding eight months during the said period) be the qualification for voting rights. “...This condition will be of particular importance in its application to the Indian immigrant population. Secondly, we consider that the registration of voters should not be compulsory or automatic but should be restricted to those who apply for it,” he noted in the Commission report.

However, mindful of the sensitivities of the local elite, the Sinhalese and Jaffna Tamil whose leader Ponnambalam Ramanathan was openly critical of the universal franchise; the British left the Ceylonese leaders to address the concerns over the enfranchisement of Estate Tamils.

When they had their way, the first thing the local Sinhalese elite (with the help of G.G. Ponnambalam) did was to disenfranchise the majority of Tamils of Indian origin.

D.S. Senanayake, who feared the rise of leftist activism of N.M. Perera’s LSSP in the plantation trade unions and the emerging electoral challenge, disenfranchised Estate Tamils under the Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948 and Indian-Pakistani Citizenship Act of 1949. That was the prelude to a host of electoral manipulations and gerrymandering that would haunt Sri Lanka in the latter decades. After mass repatriation of disenfranchised Tamils under the Sirima-Shastri pact, J.R. Jayawardene, the first executive president, granted citizenship rights to the rest, who opted to stay here.

Sri Lanka’s treatment towards Estate Tamils, who toiled for generations in tea plantations, under sub human conditions is indifferent, at best and callous, at worst. Only the absence of Jim Crow laws makes it different from the other brutal legacy in the American South.

Now, the decades of government neglect has condemned plantation Tamils to an inescapable cycle of poverty. According to 2009 data, almost half (46 per cent) of 25-year-olds or above in estate the Tamil community have not schooled up to primary level (Grade 5) while another 32 per cent have only completed primary level education (Sri Lanka Human Development Report 2012). According to these numbers, three-quarters of the estate Tamil community have not studied beyond the primary level. The national average for those two categories is 18 per cent (below primary) and 25 per cent (primary). Statistics also reveal that only three per cent of estate Tamils have passed the GCE Ordinary Level and the GCE Advanced level examinations. The national averages are 16 and 14  per cent respectively.

per cent respectively.

Estate children are more likely not to attend primary school (4.4 per cent vs. 1.6 per cent of rural kids), according to another report by the UNICEF. Estate drop out rate is higher than the national average. Ten per cent of estate children drop out before the junior secondary level; four times the average of rural children (2.8%).

One reason for the higher rate of school dropouts in the estate sector is the absence of secondary level schools. As of 2000, 68 per cent of plantation schools were classified as Type-3 schools which only have classes up to the primary level. Poverty is also a factor that drives away estate children and other kids of low income families from school. (For instance, 60 per cent of children from families of the highest income quintile proceed to upper secondary education in Sri Lanka; this is twice the size of children from families of the lowest income quintile, according to a World Bank study in 2007)

The absence of education infrastructure and entrenched poverty in the estate sector has stymied the upward mobility of the members of the community. The structure of the plantation economy, which has not changed much since the turn of the last century is also a major handicap for the mobility of the plantation workers. Plantations which rely on cheap labour of those men and women have little incentive to create real opportunities for the upward mobility of the members of the estate Tamil community. A glance through the disparity of social indicators of plantation Tamils vis a vis the national figures would also betray the boastful assertions of the welfare of plantation workers.

The literacy rate of plantation Tamils is 66 per cent (Men: 79; women: 52), far below the national average (Department of Census and Statistics,1990).

Forty four per cent of estate children below age of five are underweight, far higher than the national average of 29 per cent (2000). The figure was down to 30 per cent by 2007, still higher than the national average of 21 per cent. Infant mortality rate was 16 per cent, twice the national average (2010)

The disparity in access to upper secondary education is the greatest in the plantation sector. Only 54 per cent of estate children were enrolled, compared to 86 and 81 per cent for urban and rural areas, respectively (Sri Lanka Human Development Report). And only 13 per cent of Estate Tamil children proceed to the GCE Advanced level, which is way behind the national average of 39 per cent.

Those figures also belie a rather disturbing fact: The Central Province where the Tamils of Indian Origin account for 56 per cent of the total population has over 40 per cent of enrollment in the upper secondary education, coming second to the Western province.

That Estate Tamil children, who account for over half of the student population claim for less than one-third of the advanced level enrollment denotes a grave structural anomaly in the education sector within the province, which smacks of extreme segregation of education resources.

(1).jpg) Also some other statistics are not as rosy as they appear to be.

Also some other statistics are not as rosy as they appear to be.

According to the Central Bank, poverty in the estate sector fell dramatically from 32 per cent in 2006-2007 to 11.4 per cent in 2009-2010. (Poverty rate in the estate sector was 38.4 per cent in 1995-1996) The decline is in line with the fall of the national poverty levels from 26 in 1990 to 4.2 at present. However, a majority of the more than three million people who were lifted from poverty during the past two decades are living on the fringes of the official poverty line. This includes the vast majority of estate Tamils.

According to a paper by the Centre for Poverty Analysis, if the official poverty line is increased by mere 10 per cent, nearly 800,000 people would fall under it, increasing the poverty rate to more than12 per cent of the population.

Those figures speak of entrenched official apathy towards Estate Tamils. However, more than the national political leadership, the local political elites of the Upcountry Tamils are culpable for the grim plight of their community.

The problem lies, more than anything else, in the very political structure of estate Tamils, the Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC) and other minor parties, which have served to maintain the status qua of the local Tamil political elites -- Arumugam Thondaman, et al. The Indian Tamil political leadership thrives in the servitude of its followers and has little reason to create opportunities for the local youth, whose very mobility would challenge the existing status quoof the estate Tamil communities. Those were the very reasons that the Tamil political leadership in the 1930s objected to universal suffrage.

However, a responsible government should not permit the segregation of the estate Tamil community from the wider Sri Lankan society. Having tackled countrywide poverty and confined it to a few urban pockets, to the former conflict zone and to the estate sector, the government is now better disposed to take long term measures to fight the inequities in the estate sector vis a vis the rest of the country. The best way to address poverty and low social and educational achievements within the estate sector is to reduce the dependence of the estate workers on plantations. Only enhanced educational opportunities and affirmative actions in education and employment could break the cycle of poverty within the estate community. In fact, recent studies show that the most financially stable families in the estate sector have income outside the plantations, many having family members working in the Middle East.

In a more accommodating society, one would expect the government to offer special quotas in university admission and public service recruitment to the members of vulnerable communities as a means opposed to discrimination. The government can also expand education infrastructure in the estate sector and offer scholarships to kids from those communities to study in private universities. It can revamp the existing poverty alleviation programmes such as Samurdhi, which has degenerated into a political project, to target communities who are in need of government assistance.

The bottom line is that the dire conditions of estate Tamils are an indictment of the nation at large. Sri Lanka should give back to the people, who for centuries toiled in tea plantations, of which foreign exchange earnings financed the country’s extensive welfare system. Let alone, Ceylon tea, we would have been lesser known in the world without Murali, who himself is of Indian Tamil origin. It is a crime that those hardworking people have been left out by the very system which they have laboured to build and nurture for centuries, without receiving much in return.

Follow Ranga Jayasuriya @RangaJayasuriya on twitter.