Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Shifting of large surplus labour in low productive agriculture, state-owned enterprises (SoEs) and the public sector could address the private sector’s cry for want of labour, according to a veteran economist.

Shifting of large surplus labour in low productive agriculture, state-owned enterprises (SoEs) and the public sector could address the private sector’s cry for want of labour, according to a veteran economist.

Sri Lanka’s agriculture sector is the most unproductive as its employees that represent 30 percent of the labour force, adds only 10 percent to the economy.

SoEs have been a major instability factor to the economy and the public sector labour force has more than doubled during the last decade leaving skills vacuums in almost all industries in the private sector labour market.

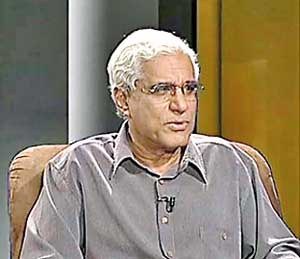

“You get businesses complaining today about lack of labour. But we see excess labour in agriculture, SoEs and the public service because we have strong incentive structure in them for them to remain there,” said the former Director, Economic Affairs at the Commonwealth Secretariat, Dr. Indrajit Coomaraswamy.

Sri Lanka’s unemployment rate is around 4 percent in recent times which is considered as near full employment.

“It’s perfectly rational for people to remain in low productive agriculture because they get free water, subsidy on fertilizer, guaranteed price, they don’t pay taxes. So, as long as you incentivize them to stay there, the outcome will be 30 percent of the people producing just 10 percent of GDP,” he remarked.

Since late 1970s, Sri Lanka has pursued a welfare model with the sole motive of the political masters to remain in power.

Most of these welfare schemes were directed at their voter base but the practice has created a dependency syndrome which the country is now unable to come out of.

“The current development model which is broadly welfare-based is no longer affordable nor has it delivered the desired outcomes. Instead we need to move to an approach which is far more focused on productivity and competitiveness,” Coomaraswamy noted.

However both, budget 2015 and the interim budget of the new government have done diametrically the opposite to what should have been done to ensure a sustainable higher economic growth.

State sector salary increase by a massive Rs.10,000 de-linked to productivity enhancement can be cited as an example.

What is more upsetting is that university pass-outs too want to get into the public sector.

“Again, it’s perfectly rational for the young to look out for a public sector employment because given the job security, life time income stream, the non-contributory pension schemes, the status and the marriage prospects, it’s a rational thing to do,” Coomaraswamy noted.

Sri Lanka’s public sector over the years has been used as a social protection.