.jpg)

The Excise taxes on products such as cigarettes and alcohol are a significant source of government revenue. Understanding how these taxes should be adjusted in keeping with price increases and being diligent in implementing these adjustments carry huge revenue implications. The decisions on taxation require technical evaluation and are significantly in the hands of Sri Lanka’s bureaucrats.

This Insight explores the loss incurred to the government by the negligence of bureaucrats. The latest data reveals that the mishandling of this professional function with regard to cigarette taxation has cost the Sri Lankan government Rs.76 billion over the last eight years.

Space for taxation of cigarettes

Sri Lanka collects over 60 billion in revenue from the Excise taxation of cigarettes. A 25 to 30 cent increase in Excise taxes can increase revenue by about a billion rupees. Therefore, attention to setting taxes professionally will have huge benefits to the government.

The cost of manufacturing a cigarette – take the brand that has over 80 percent market share – is less than 5 percent of the retail price. That leaves a large margin of space for taxation. The Excise tax rates in Sri Lanka on cigarettes have been in the range of 65-72 percent during the 1990s and in the early years of the Mathata Thitha (in 2006). In addition to this the government also imposes the normal statutory taxes such as VAT.

Inconsistency and reduction of taxation

However, since 2007 the government fail

.jpg)

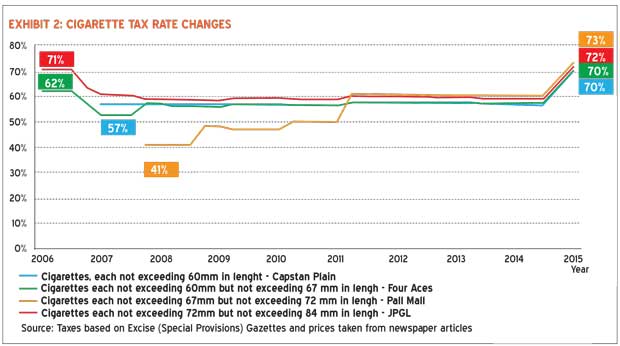

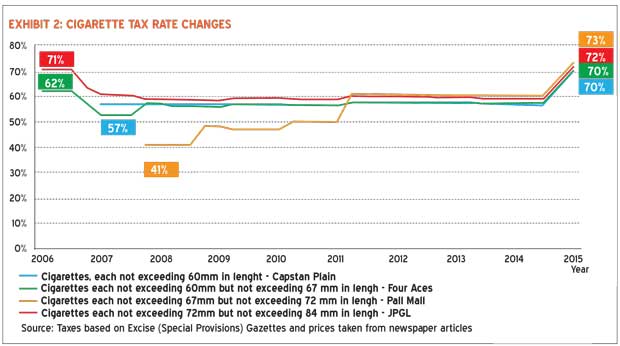

ed to be diligent in the way that taxes were adjusted and since 2009 there is evidence of outright negligence. The Excise tax rate of the most popular brand was 70.8 percent in 2006 and declined to its recorded lowest of 55.3 percent by September 2008; it increased to 61 percent in 2011 and then fell back to 59 percent and stayed there since 2012.

Sudden correction in taxation after eight years

On October 24, 2014, the Finance and Planning Ministry increased the Excise tax rate, quite suddenly, back to the 2006 level, by taking it to 72 percent. That is, after a lapse of over eight years. The Ceylon Tobacco Company did not increase its price in response to this tax increase. This is despite a growing gap since 2002 where affordability (per capita incomes) has increased faster than the cigarette prices. These developments help to establish the feasibility of the 70+ percent Excise tax rate for the government and for the manufacturer.

Cost of negligence – over eight years

Over the past eight years taxes were significantly and systematically reduced from this 70+ percent rate that exists at present and existed prior. Research and writings about this by independent organisations seem to have had an impact, going by the very sudden nature of the correction adjustment on October 24, 2014. This is shown for all types of cigarettes in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1 shows the calculations of the additional revenue the government would have received each year, if Excise taxes had been held at the current 70+ percent rate over the last eight years. This adds up to a total of Rs.76 billion – or an average of Rs.9.5 billion a year. (However, some of this lost revenue would be rerouted to the government through statutory taxes on corporate profits).

.jpg)

Who is responsible and who pays?

Who is responsible for such huge negligence and the resulting loss to the government? The task of setting Excise taxes and revising them in a proper manner lies with the Finance and Planning Ministry, which is steered by Sri Lanka’s most powerful bureaucrats. The lack of consistency and sheer professional negligence in carrying out this task properly (assuming that there was no criminal collusion with the company that benefited) is seen in Exhibit 2 and also from the lack of consistency in tax rates in the past for different cigarettes and the irregularity of tax changes – sometimes several times a year, sometimes not even once a year.

Especially in the last five years, the government has been facing a significant crisis with regard to revenue, where it has dipped to as low as 13.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Reduction in revenue results in reduction in expenditure and often it is expenditures that are of supporting and social nature that are cut. For instance, in 2013 the government cut spending on agriculture expenditure by almost 40 percent from what had been budgeted.

The Rs.9.5 billion a year loss in revenue from failure to set the Excise tax properly is equal to the total cost of Samurdhi disbursements a year. This is the government’s welfare scheme that supports about 30 percent of Sri Lanka’s households. That means Samurdhi disbursements in the last eight years could have been doubled simply by proper attention to the Excise tax on cigarettes.

Good governance is not just for politicians

The fundamental backbone of good governance is not better politicians but professional bureaucrats. In focusing exclusively on the obstacles to good governance created by politicians and Sri Lankan civil society, we may be neglecting to consider the problem of an unprofessional bureaucracy – especially at the highest level.

Bureaucrats are not necessarily only the victims of political misbehaviour - they can also be its handmaidens. The criminal destruction of files and documents in government departments that was reported to have occurred soon after the change in presidency is an indication of the bureaucratic complicity as handmaidens rather than as victims.

It is important therefore to build structures that hold bureaucrats accountable. This Insight shows that in the case of cigarette taxation, bureaucratic discretion and professional negligence has led to at least eight years of unprofessional decision-making with high costs resulting to government revenue and social welfare.

(Verité Research provides strategic analysis and advice for governments and the private sector in Asia. Comments welcome, email [email protected])

.jpg)

.jpg) ed to be diligent in the way that taxes were adjusted and since 2009 there is evidence of outright negligence. The Excise tax rate of the most popular brand was 70.8 percent in 2006 and declined to its recorded lowest of 55.3 percent by September 2008; it increased to 61 percent in 2011 and then fell back to 59 percent and stayed there since 2012.

ed to be diligent in the way that taxes were adjusted and since 2009 there is evidence of outright negligence. The Excise tax rate of the most popular brand was 70.8 percent in 2006 and declined to its recorded lowest of 55.3 percent by September 2008; it increased to 61 percent in 2011 and then fell back to 59 percent and stayed there since 2012..jpg)