Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Premalal’s team manually uproots the invasive plants saving the native species and allowing the latter to grow

Removal of damaging plants is a sustainable approach to mitigate human-elephant conflict

Experts believe that engaging the local community to manage protected areas is an effective model

Apart from adults, the project now includes school programmes, educating children about conservation practices

A. M. Sugath Premalal hails from Ranawarawa and has lived with the human-elephant conflict ever since he can remember. Damaged crops, an angry elephant in his backyard, staying awake to keep the elephants away were his only memories of the jumbos. But during the past year his attitude towards this conflict experienced a change.

A. M. Sugath Premalal hails from Ranawarawa and has lived with the human-elephant conflict ever since he can remember. Damaged crops, an angry elephant in his backyard, staying awake to keep the elephants away were his only memories of the jumbos. But during the past year his attitude towards this conflict experienced a change.

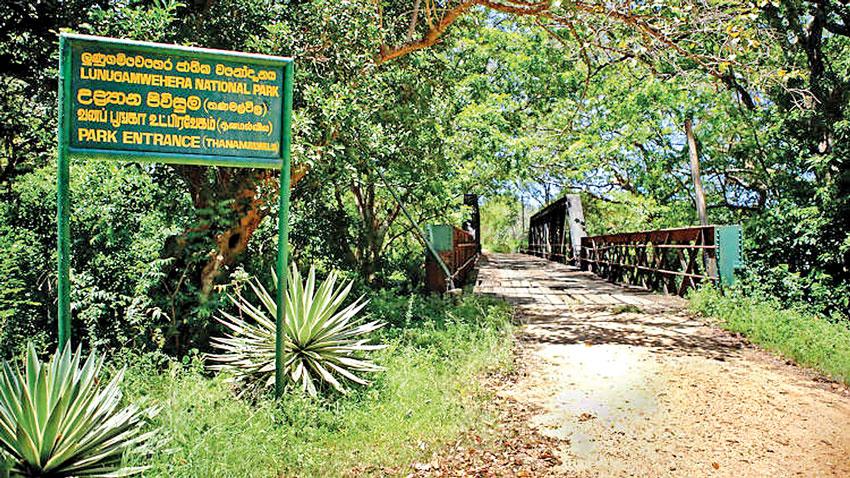

This was after he got involved in removing invasive plants that had invaded the Lunugamvehera National Park. Invasive species which cause problems to biodiversity and most protected areas in Sri Lanka have taken over areas where other plants grow. Invasive plants are masters at taking over the land area from the natives; they spread, grow and reproduce fast and they have a way of suppressing other plants. If animals need to be managed inside protected areas, it is also important to think of managing the landscape and their requirements, primarily food. This is why the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) has opted for a scientific approach to remove invasive plant species. The project is being carried out with the backing of the Federation of Environmental Organizations (FEO).

Mechanical versus manual removal

By the time we reached L Wanguwa, down Demaliya Road, Premalal’s team was busy at work. They report to work at 7.30am and sign off at 4.30 pm irrespective of rain or sunshine. The L Wanguwa area was once dominated by invasive plants, namely Lantana camara (S. Gandapana) and Eupatorium odoratum (S. Podi singho maran). The team manually uproots the plants, saving the native species and allowing them to grow. The FEO had been successful in removing Xanthium indicum (agada) which is an invasive alien plant species which grew along the tank beds of the Minneriya National Park. As it was a success they were looking for other areas to replicate their work and that is how they identified Lunugamvehera National Park.

Usually, invasive plant management is done using machines, but the team also scrapes up the entire layer, including invasive species

For Prof. Enoka Kudavidanage, Senior lecturer in Ecology and Conservation Biology at the Sabaragamuwa University, the Lunugamvehera National Park is a familiar terrain. “I have worked in Lunugamvehera since 2002, but the important part is that you have to work in an area where you can make an impact. Here, nobody has done invasive species management in a substantial manner. Other parts were extensive and we had to try it out in a place where we were confident. Lunugamvehera, although less noticed by tourists, is a fantastic park. I have been studying leopards and wild animals here for a long time. But the sad part is that the park was taken over by lantana and podi singho maran. But you just can’t step into a park and start a project. Therefore, we did some ground work. We measured the extent of the park covered by invasive species, how to remove them and the method. Usually, invasive plant management is done using machines, but once you scrape up the entire layer including invasive species in the clearance, who would come back? They are more successful in taking over the land area than natives. Apart from how are we going to do this, who will be doing it? What can we learn from it and how could we replicate it? These were questions that we had to answer,” said Prof. Kudavidanage.

I have worked in Lunugamvehera since 2002, but the important part is that you have to work in an area where you can make an impact. Here, nobody has done invasive species management in a substantial manner - Prof. Enoka Kudavidanage Senior lecturer in Ecology and Conservation Biology Sabaragamuwa University

Using machines we remove the top layer of soil and this damages other native species as well. But now we remove them manually. We see a reduction in the growth of invasive species during the third round. It has been two years since we started this project

- K. Sanjeewa, Volunteer Tracker at Lunugamvehera the Park

After we started this project we see a reduction of elephants frequenting the villages because now they have food inside the park. Therefore there are positive results in removing invasive plants. We are also aware of habitat management

- A. M. Sugath Premalal Project Member

In early 2021 the aim was to clear about 900 hectares of land comprising Lantana camara (S. Gandapana) and Eupatorium odoratum (S. Podi singho maran). Through this project, close to 700 hectares of land has been cleared; not just once but on several occasions. “If you take it off just once and let it grow back, it’s a waste of time and energy. What needs to be done is to keep on removing if you plan to provide native vegetation for animals to eat. In this case you have to wait till they grow back. For this you need to keep on removing the invasive plants until some of the seeds in its seed bank have been exhausted. We are selectively removing the invasive species while sparing the seedlings of native plants to facilitate their growth. It’s like removing the enemies. Native plants now don’t have any competition,” Prof. Kudavidanage added.

Invasive plants have invaded the Lunugamvehera National Park

During the past five years, K. Sanjeewa, Volunteer Tracker at the Park, had observed the difference in removing invasive plants using machines versus manually. The L Wanguwa area was once covered with invasive plants even after the plants were bulldozed and the piles were subsequently burnt. “Using machines we remove the top layer of soil and this damages other native species as well. But now we remove them manually. We see a reduction in the growth of invasive species during the third round. It has been two years since we started this project and we have seen a change in Rathmalwewa, Sarvodaya and Galwewa road. We have completed three rounds while maintaining these areas. Now, the spread of invasive species is around 2% and around 95-98% has become extinct. At the time we bulldosed the invasive plants, they would grow back in around one or two months with the rains. This is because the seeds were still intact,” said Sanjeewa.

The teams continue their work despite insect bites and occasional pricks from thorny bushes. The Department has provided them with boots as a safety measure. But the teams have less complaints because they are not only aware of their responsibility to manage the habitats, but they also have a source of income to feed their families.

Community engagement

Apart from Premalal’s team, another team is involved in the project. Premalal had earned an income through fishing and mason work prior to COVID. But once COVID struck he had no source of income to feed his family. This is when a friend had informed him about this project. The very next day, he had decided to join and he has been actively involved in it for over a year. This project is now his only source of income hence he takes a keen interest in completing the tasks assigned to him. “When you are doing protected area management you have to understand that you cannot isolate the local communities. That’s the biggest mistake we are doing. If you think of a protected area as an island, put a fence and isolate the community, that’s not going to work. They live right next to the park, they suffer from the human-wildlife conflict and when you take Lunugamvehera it is surrounded by villages. Since 2002 until recently, people didn’t have a favorable perception of the park. There are no tourists and no proper income apart from a few jeeps. They are suffering from animals eating their crops. They do illegal fishing and are slapped with fines. The perception wasn’t good and we thought to use this opportunity to create an amicable environment between the park management and the local community,” Prof. Kudavidanage added.

All individuals involved in the project lost their employment at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The teams are remunerated for their efforts to maintain the park and ensure that its inhabitants are managed within the park, thereby minimizing the human-wildlife conflict in the surrounding areas. A majority of these people are poor and to achieve conservation goals, they need to be given something in return. Prof. Kudavidanage further said that many of these people haven’t been into the park. “But now they see the animals and they know that they’re doing something for their survival. Therefore, it’s a win-win situation,” she said.

Prof. Kudavidanage said that engaging the local community to manage protected areas is an effective model that could be carried out around the country. Therefore the local community is involved in habitat management, not just in the removal of invasive species. This approach not only provides them with employment, but it also provides forage for animals. “A healthy environment can maintain animals,” she added.

One of the fundamentals to mitigate the human-elephant conflict is to bring about attitudinal changes in people. This project has succeeded in making people realise that there are better approaches to mitigate this conflict. Premalal’s perception about the project and the conflict provides a fine example. “We have been living with the human-wildlife conflict. Elephants have damaged my crops and we stay awake to ensure that the elephants don’t come to harm us. We do have problems with elephants irrespective of electric fences. They know how to damage this technology. I don’t know whether there’s a way to mitigate this conflict. But after we started this project we see a reduction of elephants frequenting the villages because now they have food inside the park. Therefore there are positive results in removing invasive plants. We are also aware of habitat management,” Premalal underscored.

Apart from adults, the project now includes school programmes, educating children about conservation practices. Initially, they would view elephants as pests, who had come to destroy crops in their backyards. But now, they visit the Park as tourists and they see elephants from their safari jeeps and they enjoy with safety. They had no time to admire birds, but now they visit the park with their binoculars and a field guide to observe birds. “These approaches change their attitudes towards animals,” Prof. Kudavidanage observes. “This change in mindsets is beautiful to watch,” she said.

The children are also taught about waste management and global environmental issues to name a few.

In terms of sustainability the project has already established three community-based organisations in three surrounding villages. The villagers have been provided with a community hall to discuss their issues while continuing with the project.