14 Dec 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s efforts to achieve gender parity in economic and political participation have suffered severe setbacks over the last few years, due to consecutive crises, most notably the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic collapse. The associated challenges have derailed progress towards gender equality and achieving Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic collapse. The associated challenges have derailed progress towards gender equality and achieving Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In the face of Sri Lanka’s worst economic crisis, women’s socioeconomic empowerment remains more relevant than ever. This Policy Insight identifies the existing gaps under SDG 5 aimed at achieving gender equality and recommends policy measures to bridge the gaps for a swifter, more inclusive economic recovery.

Gendered impacts

While the burden of the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka falls on every citizen, women are among the most vulnerable to its impacts. This is because of their disadvantaged position in accessing resources, representation and decision-making and lack of opportunities for economic empowerment. When a financial crisis spills over into the home sphere, women, as the primary caregivers at home, face additional burdens in meeting the care needs with limited resources. These responsibilities restrict women from participating in income-generating activities. Empirical evidence shows that while both women and men are affected by job and income losses during crises, the impact on women is more severe than on men.

For example, COVID-19 hit employed women harder than employed men in Sri Lanka. A higher reduction in the employed population and a higher increase in the economically inactive population for women were evident from the available data. Similar labour market implications can be expected as consequences of the current economic crisis, given that more women are in informal jobs, which are more vulnerable to economic shocks and have weaker social protection coverage.

Possible austerity measures to overcome the crisis, such as increasing taxes, reducing government expenditure and limiting investments in health, education and care services, would result in unintended and adverse impacts on women, especially those already vulnerable to socioeconomic shocks. In this setting, evaluating women’s role and contribution in carrying out unpaid care work and how it affects their economic empowerment (SDG Target 5.4) and ensuring women’s effective participation and decision-making ability in every sphere of life (SDG Target 5.5) are of great importance.

Unpaid care work in Sri Lanka

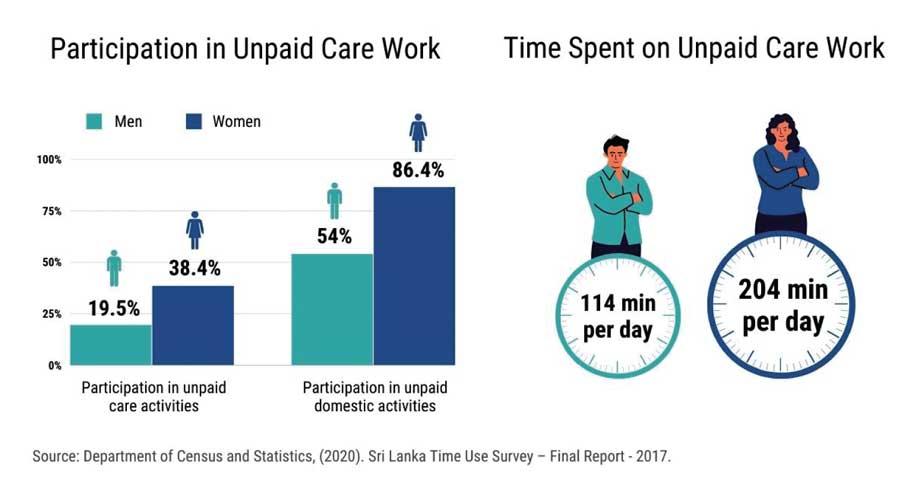

Unpaid care and domestic work refer to all non-market, unpaid activities carried out in households. Traditionally unpaid care work is considered ‘women’s work’ and women bear the greater responsibility to perform these tasks. Globally, women perform 76.2 percent of the global unpaid care work, which is more than three times the unpaid care work by men. In Sri Lanka, women participate in unpaid domestic and care activities more than men (Figure 1). Moreover, a substantial difference is evident between the time spent by men and women on unpaid care work.

Unpaid care work is a crucial barrier to female labour force participation (FLFP) and hinders women’s economic empowerment. Women account for 73.5 percent of Sri Lanka’s economically inactive population. Of these economically inactive women, 60.8 percent indicated that household work restrained them from participating in economic activities.

On the other hand, merely 3.7 percent of economically inactive men stated household work as a reason for inactivity. Unpaid care work deters FLFP, leading to gender disparities in the labour market (such as gaps in employment outcomes, wages and pensions) and a lack of financial security for women, due to employment in informal and vulnerable sectors or unemployment. Further, due to the gendered nature of unpaid care responsibilities, employed women face a ‘double burden’, i.e. balancing employment and domestic duties.

Gendering care work makes unpaid care work less visible and less recognised. Accordingly, the issue of unpaid care work has three interconnected dimensions: recognition, reduction and redistribution, known as the 3Rs. Target 5.4 emphasises these 3Rs; recognition and valuation of unpaid care work (recognition) by providing public services, infrastructure and social protection policies (reduction) and the promotion of shared responsibility at distinct levels – i.e. household, institutional and national (redistribution) within the household to reduce and redistribute these tasks.

Women in decision-making positions

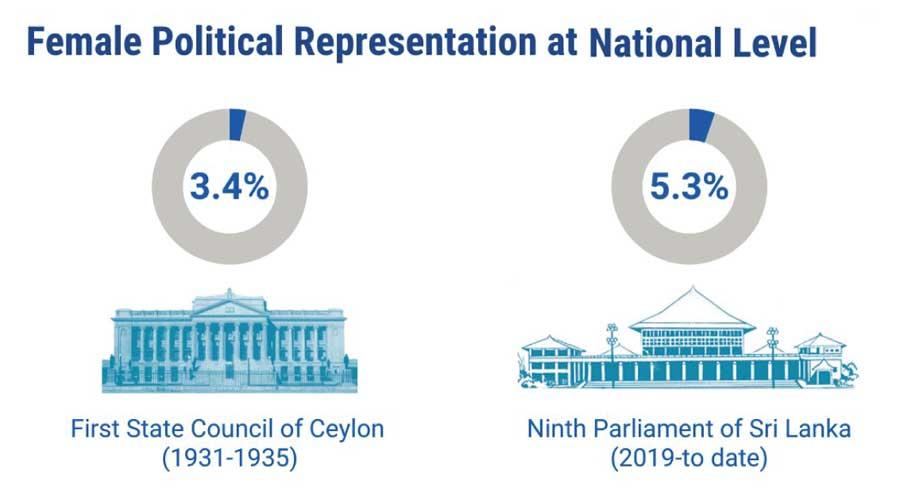

Despite Sri Lanka’s creditable achievements in human development indicators, the country has failed to improve female representation in decision-making positions. For example, the progress in enhancing women political representation throughout nine decades has been abysmally slow (Figure 2). Likewise, women are acutely under-represented in higher managerial positions in Sri Lanka, with a meagre 8.8 percent of firms having top female managers.

Women’s leadership at various levels generate many benefits. At national level, women’s leadership promotes policy agendas focused on inclusivity and empowerment. At business level, having women as board members correlates with the better financial performance of organisations than those with low female representation. Further, diverse perspectives and talents can be incorporated into boards by maintaining a gender balance at higher decision-making levels. Yet, many constraining factors prevent women from taking leadership positions in political, economic and public life. These constraining factors are visible at diverse levels (family, community, school and labour market). For instance, lack of recognition for female leadership, deep-rooted social norms, mobility restrictions, uneven distribution of family responsibilities and cultural factors prevent women from taking active leadership roles at community level.

Conditions like ‘glass ceilings’ (where a qualified person is precluded from career advancement at a lower level within the hierarchy of their organisation, due to discrimination most often based on sexism or racism) and ‘sticky floors’ (biased employment pattern that keeps workers, mainly women, in the lower ranks of the job scale, with low mobility and invisible barriers to career advancement) prevent women advance in their carrier ladder and from assuming leadership and decision-making positions.

Conclusion

Unpaid care and domestic chores are key barriers for women to participate in market activities, thus hindering their economic empowerment. Further, unpaid care work aggravates pressure on women during an economic crisis. Social norms and perceptions, asymmetric division of labour at household level, issues in accessibility and affordability of technologies and a lack of gender sensitivity in policies and programmes make unpaid care work a weighty burden on women. The lack of women in decision-making positions has a cost for society, as women often have various priorities and can be more effective where it matters.

For example, greater representation of women in parliaments led to higher expenditure on education as a share of GDP. The current economic crisis should be treated as an opportunity to promote gender equality. In turn, promoting gender equality would help Sri Lanka overcome the crisis and create a more resilient economy that can effectively absorb future economic shocks.

Policy recommendations

Prioritise data collection to improve the recognition of unpaid care work: the gendered and voluntary nature of unpaid care work largely contributes to its poor visibility in the economy and its exclusion from the system of national accounts. Recognising unpaid care work by including it in national statistics is essential for many reasons; it makes women’s economic contribution statistically visible, makes unpaid work more socially valued and provides a more accurate overview of the goods and services produced within an economy.

Prioritise care work in policymaking and budget setting: Introduce specific budget lines to support and expand the types of public services or programmes that significantly release households’ unpaid care workload, recognise the contribution of carers through awareness-creation, build potential collaborations across government sectors and ensure that the needs of carers are addressed. These long-term strategies can assist in making care a national priority.

Provide affordable and quality childcare options: The availability of affordable childcare would reduce the double burden employed women face and encourage FLFP. Further, options that positively impact FLFP, such as expanded preschool/school hours, can be introduced in the short term without requiring additional resources when a country’s resources are constrained.

Adopt affirmative action for higher female political representation: Quotas for women effectively increase female representation. The local government election results following the enactment of Local Authorities Election (Amendment) Act No. 16 of 2017 prove this. The act’s shortcomings should be considered when exploring the possibility of introducing a quota system at national level.

Allocate corporate quotas, build networks and develop skills: Experience from other countries shows that allocating quotas for women (either mandatory or voluntarily) can enhance female representation in the boardrooms. To encourage aspiring female leaders, companies can adopt medium-term strategies such as creating networking opportunities targeting women, introducing mentorship programmes and providing on-the-job training and long-term approaches to foster gender-sensitive organisation cultures and management styles.

(This Policy Insight is based on the comprehensive chapter on ‘Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment’ in the ‘Sri Lanka: State of the Economy 2022’ report, the annual flagship publication of the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS))

05 Nov 2024 26 minute ago

05 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

05 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

05 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

05 Nov 2024 4 hours ago