23 Sep 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Bangalore, the capital of the Karnataka State in India was in flames last week. Hundreds of shops and vehicles belonging to Tamils hailing from the adjacent State of Tamil Nadu had been set on fire and many Tamils had been assaulted.

Bangalore, the capital of the Karnataka State in India was in flames last week. Hundreds of shops and vehicles belonging to Tamils hailing from the adjacent State of Tamil Nadu had been set on fire and many Tamils had been assaulted.

In one place 42 buses parked in a depot belonging to Tamils had been torched.

Violence broke out in the State holding the Tamils hostage for about five days following a ruling by the Supreme Court of India that Karnataka released 12,000 cusecs (cubic feet) of water from its dams built across Cauvery River to Tamil Nadu.

In response to these attacks on Tamils, violence spread, though in a low proportion, in some areas in Tamil Nadu as well against Kannada people.

In response to these attacks on Tamils, violence spread, though in a low proportion, in some areas in Tamil Nadu as well against Kannada people.

Tamil Nadu State government had to beef up security for the popular film stars in the State such as Rajnikanth and Prabhu Deva, who are of Kannada origin.

A dawn-to-dusk State wide bandh (shut down) was held in Tamil Nadu on September 16. Many inter-State bus and train services were cancelled. During the protests organised by the Nam Thamilar party one youth died of self-immolation.

In Sri Lanka too several Tamil organisations in the north launched protests against the attacks on their brethrens In Karnataka.

In spite of all these incidents taking place for about a week, it is interesting to note that Sinhala and English media in Sri Lanka, except for carrying one or two inside stories, totally blacked out the carnage in Karnataka and the low profile response to it in Tamil Nadu and Northern Sri Lanka.

The lack of concern on the part of these media outlets on these serious incidents, which have much to do with power devolution in a neighbouring country, is incomprehensible as the concept of devolution of power has been debated for more than three decades in the island.

However, Tamil newspapers in Sri Lanka had given wide coverage for these incidents. Almost every day in the week they carried several front page stories sometimes including the lead story.

However, Tamil newspapers in Sri Lanka had given wide coverage for these incidents. Almost every day in the week they carried several front page stories sometimes including the lead story.

We had seen this kind of divided reportage in the past as well, though with different facets. For instance, when the killer tsunami hit the South East Asian countries including Sri Lanka on December 26, 2004, Sri Lankan media were seen highly divided. Sinhala and English media highlighted the human tragedy in the south and west, while providing only statistics about the north and the east.

Not to be outsmarted by these reports, the Tamil media highlighted only the death and destruction in the north and the east making a nominal reference to the south. Ridiculously one newspaper carried a headline which read “Huge destruction in the north and the east due to rising tidal wave.”

Thus, moved by the reports they had read, Sinhala people took their relief provisions to the south, while the Tamils and the Muslims rushed to the north and the east respectively. This was the outcome of the media’s thinking that it should always pacify its clientele for it not to be alienated from them.

Needless to say, that the survival of the media which goes against or does not retain the interest of its clients would be in jeopardy. But, the Karnataka carnage or tsunami in “other areas” is not something that media clientele would ignore.

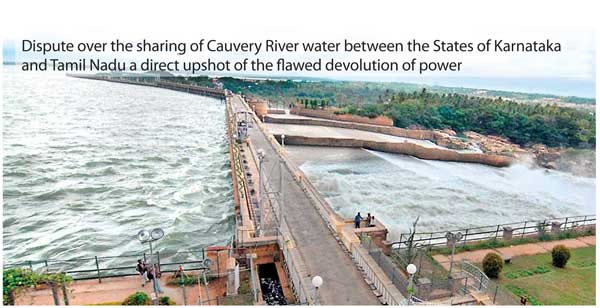

The dispute between the two southern Indian States, over the sharing of Cauvery water is interesting  and worth studying. Cauvery rises in the Brahmagiri hills of the Western Ghats in Coorg (Kodagu), Karnataka, at a height of 1,340 metres.

and worth studying. Cauvery rises in the Brahmagiri hills of the Western Ghats in Coorg (Kodagu), Karnataka, at a height of 1,340 metres.

From its source at Talacauvery – a revered and much-frequented pilgrimage spot – the Cauvery traverses 850 kilometres through Karnataka and Tamil Nadu States and the Union Territory of Pondicherry, before emptying into the Bay of Bengal at Poompuhar in Tamil Nadu.

Karnataka has built three major irrigation dams on the Cauvery system. The Harangi Dam has a storage capacity of 8.5 thousand million cubic feet (tmcft), the Kabini 19.5 tmc ft.

The largest irrigation dam is the Krishnaraja Sagar (KRS), built in 1924, with a storage capacity of 45 tmc ft. The KRS system has created the wealth of the Mandya, Karnataka’s fertile sugar bowl. The system irrigates roughly 200,000 acres, according to some report.

Cauvery crashes down nearly 30 metres at Hogenekkal, marking its entry into Tamil Nadu. It is welcomed there by the famous Mettur Dam, which has a storage capacity of 93.5 tmc ft. The inflow and the out flow of the dam which was built in 1930 has been so vital for the people of the State that almost all news bulletins of the Tamil service of the All India Radio (AIR) provides a graphic description on them.

Although the capacity of the Mettur Dam is larger than the total capacity of all major dams in Karnataka, the inflow of water into it is primarily dependent on the release of water from the Karnataka reservoirs, and it is this that lies at the root of the running dispute between the two States.

Sharing of Cauvery water has been a controversy between the two States since the beginning of the 19th Century. The first negotiation between the two parties had been held in 1807 and two agreements had been inked in 1892 and 1924, the year in which the Karnataka’s KRS Dam was built.

Under the first agreement the then Princely State of Mysore (Karnataka) had agreed to get the consent of the then Madras Presidency of British India (Tamil Nadu) if the former intended to build any dam across the river. Both States were allowed to build two dams under the second agreement, which was valid only for 50 years and lapsed in 1974. Tamil Nadu argues that its agriculture and the power generation have been severely affected by Karnataka’s unfair retention of Cauvery water. The Tamil Nadu authorities point out that the annual power generation from the Mettur power plant, which was 175 million units between 1940 and 1974 has gone down to a mere 93 million units since then and the summer paddy crop which is called kuruvai, in the once prosperous Thanjavur District, has come down drastically from 450,000 acres to 75,000 acres, creating a huge unemployment problem.

On the other hand, Karnataka contends that though the State contributes the largest amount of rain water to the flow of Cauvery, 64 percent of the Cauvery basin in Karnataka is drought-hit whereas it is only 29 percent in Tamil Nadu as the latter is blessed with more rain. Also the Karnataka authorities argue that while about 1,200,000 hectares is under irrigation in Tamil Nadu Cauvery irrigates only a little over 300,000 hectares in their State.

However, as a tribunal appointed to solve this problem in 1990 pointed out, this was a human problem rather than mere charts, tables and engineering jargons. When the tribunal ruled in June 1991 that 205 tmcft of water has to be released annually to Tamil Nadu, violence against Tamils erupted in many parts of Karnataka, as happened last week, killing 12 Tamils. In protest against the ruling a Karnataka farmer committed suicide by jumping into the Kabini reservoir.

The dispute over the sharing of Cauvery River water between the States of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu has been a direct upshot of the flawed devolution of power to various States in India.

In other words, States in India seem to have more powers devolved to them than what they should have been, in respect of some issues such as inter-State waterways.

Indian leaders were the gurus for Sri Lanka in 1980s in devolution of power in the island. However, Sri Lankan leaders have managed to totally get hold of the powers for the centre, in respect of inter-provincial waterways and thoroughfares, when devolving powers to the provinces.

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago