14 Oct 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

MTI Consulting, with international trade consulting experience across 43 countries in the last 20 years, has opined that developing economies like Sri Lanka needs a radical mindset change from the concept of exports to being an integral part of international supply chains.

“The very word ‘ex-ports’ and its practice in markets like Sri Lanka, means the focus is on getting it off your ports! This is not what the international demand chains are demanding today and to be a profitably integral part of the enabling supply chains (to these demand chains) requires a truly global mindset and cross-border collaborations, not an insular mentality,” said MTI CEO Hilmy Cader.

A critical look at SL’s export performance

Over the last 10 years (up to 2015), Sri Lanka’s total exports have grown only by 7 percent (CAGR). During the same period, apparel grew by 5 percent, tea by 8 percent and rubber by 12 percent (all in CAGR terms). Statistically, ICT has recorded an impressive 23 percent CAGR but this is from a low base and is based on a sample survey to establish the export revenue. These top sectors have continued to contribute as much as 70 percent of Sri Lanka’s exports.

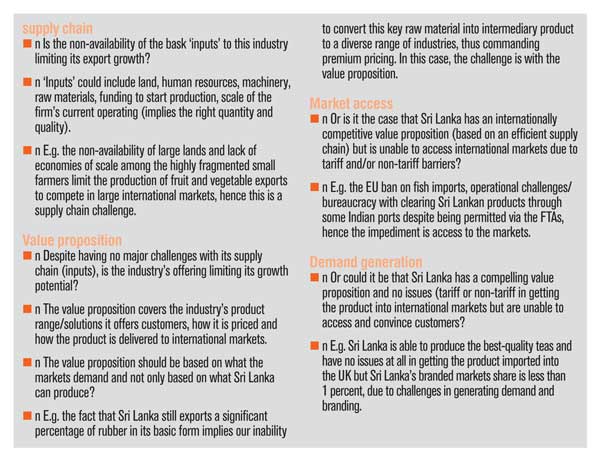

With the exception of the apparel sector and solid tyres, the supply chain (in particular) and the demand chain for other sectors are highly fragmented, with most businesses being unable to scale-up their operations. This fact has been proven by the 3700 plus Sri Lankan exporters, who export over 30 diverse product categories. The share of branded and high-tech exports as a percentage of Sri Lanka’s total exports is at a very low level, even when compared to the relevant emerging Asian competitors. The extremely low spend on research and development (R&D) (as a nation) could be a contributory reason.

Five strategic export policy decisions SL needs to confront

Definition of exports: The Sri Lanka Export Development Board (SLEDB) Act defines exports as products/commodities and services. However, neither has the SLEDB managed nor accounted for tourism and foreign employment but continues to promote ICT, medical tourism and educational services. Therefore, the export earnings that the SLEDB publishes include all commodities and only some services.

Measurement of exports: Sri Lanka’s measurement of exports is entirely based on revenue (essentially top line) and thereby ignores the degree of value addition that would help determine export profitability to the country, as this is what Sri Lanka will eventually benefit from. Focusing on such a measure will help drive the country’s export policy and incentives and subsequently aid the actions of exporters to the sectors which will optimize Sri Lankan export profitability. Partly related to the above is the fact that the current policy framework does not encourage import substitution of export-related inputs.

Definition of export earnings: As currently practiced, what is considered export earnings is the declared value of a good when it leaves a Sri Lankan port, with no consideration or interest in what happens beyond that point. While this encourages maximum value addition within Sri Lanka, it does not encourage Sri Lankan companies to become multinationals – which will require varying degrees of in-country value addition in export markets and even multi-country sourcing – provided that the Sri Lankan exporters earn higher profits and that these profits are repatriated to Sri Lanka.

Exportable resource optimization: The current approach to exports is based on each sector attempting to maximize its export revenue. Given the limited size of the Sri Lankan supply chain (natural and human resources) and the quantum increase in exports that is targeted (while ‘feeding’ the growing local demand), there is bound to be increasing competition for the country’s natural and human resources. Allowing this to be dictated entirely by the ‘invisible hand’ may not be in the long-term strategic interest of the country and could also lead to socio-economic challenges. Therefore, a macro resource allocation model and policy is strongly recommended.

Multiple institutions in overlapping export promotion roles: Today, the role of export promotion in the key sectors of apparel, tea and ICT (constituting approximately 65 percent of our exports) is also being performed by their industry-specific bodies, with access to a much bigger promotional budget than the SLEDB. This leads to overlaps and sub-optimal efforts from a macroeconomic perspective. Given that this involves multiple ministries, it is best addressed via the Export Development Council of Ministers (which has remained dormant since 1993).

What are our base capabilities to get internationally supply-chained?

Every nation depends on certain ‘base capabilities’ to drive export growth and economic development. Assessing the world’s top exporters (for the different sectors) demonstrates one or more of these essential ‘base’ capabilities. These capabilities are the ‘platforms’ or ‘drivers’ on which nations enable profitable export industries.

Intellectual property by way of multinational businesses and brands. E.g. The USA, Switzerland, Japan, Germany. As businesses seek to capture multiple markets by taking their valuable industry expertise, skills and products to foreign markets, nations have benefitted through increased level of exports as well.

Possessing high-value natural resources. E.g. Australia, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia. These resources, if well managed, have generated significant amounts of income to such resource rich nations, becoming strong foundations for economic prosperity.

Having highly skilled knowledgeable workforce. E.g. Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, India (for ITES). As nations become increasingly interconnected, tapping into foreign labour pools becomes the standard. Certain nations may not possess adequate labour resources that they may require in which case going abroad is the probable option.

Large-scale, low-cost ‘production’ workforce. E.g. Bangladesh, China, Vietnam. Significant cost savings through cheaper foreign labour has prompted corporations to consider outsourcing key operations and functions. This has increased export activity bringing in benefits to both nations as well as businesses. Access to such global labour pools has dramatically brought down production and operating expenditure, helping businesses achieve massive economies of scale. Being a regional hub. E.g. Dubai, Netherlands. By focusing on offering key services such as ports and supply chain trade links, built and supported around their strategic locations, certain nations have managed to gain added advantages in the global stage.

On what ‘platform’ are we? What base capabilities do we possess? What do we offer currently and what other capabilities could we build, develop or groom to offer the world?

A strategic shift to TDOs – away from TPOs

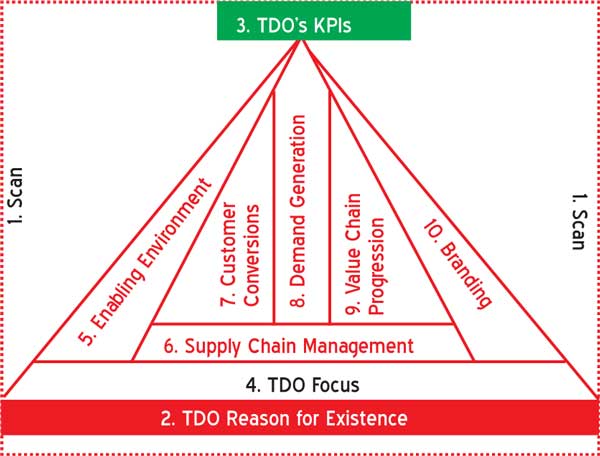

Trade promotion organisations (TPOs) have been used by governments to promote exports. But we now see a transition from trade promotion to trade development, hence the birth of trade development organisations (TDOs) – which are expected to play a catalyst role by working through and working with a multitude of other organisations – with the final intent of enhancing the country’s exports. Based on MTI’s research and experience, there are 10 aspects at which a TDO must succeed in order to be effective.

Scan: A TDO needs to be aware of its business environment and the changes that are happening in that very environment. A thorough evaluation needs to be carried out.

Reason for existence: Internal stakeholders need to be made aware of why the TDO exists. They also should be made to understand why the government is funding them.

KPIs: Criteria for the evaluation of the TDOs’ performance need to be agreed upon.

Prioritization and focus: Priorities in terms of industries, export markets, regions and value chain functions should be decided and the key personnel should be briefed.

Enabling environment: The TDO will not be able to influence everything. All aspects out of the TDOs’ control, which have major impacts on exports, need to be identified and action plans need to be devised so that internal stakeholders know how to deal with them.

Supply chain management: A strategy must be designed so that exporters/industries have the capability to deliver potential demand.

Customer conversion: A strategy should be set in place to convert potential customers (importers). Demand generation: Strategies need to be arrived at to ensure on-going demand for exports. Value chain progression: The TDO needs to actively keep tabs on whether exporters progress along the value chain and take measures to encourage them to do so.

Branding: An effective branding strategy, which deals with how to brand the country, industry, product, exporter, exporter’s brand or TDO, must be created and executed

to perfection.

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago