21 Sep 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Jeffrey Bader

On rare occasions, international issues are resolved by a dramatic, decisive development. Much more often, progress is incremental. As United States President Barack Obama has said, an administration hits more singles and doubles than home runs. This has certainly been the nature of the United States’ recent achievements in Asia.

Unlike the Middle East, which is in seemingly permanent turmoil and crisis, or Europe, whose unity and institutions are threatened, Asia is economically dynamic and generally stable. It is the fastest growing region in the world, the home of many of the companies and much of the technology driving the global economy and the source of hundreds of billions of dollars in trade and investment.

Obama believed US interests lay in deeper engagement in a part of the world marked by success stories rather than failed states, much as throughout US history its deepest overseas ties have been with a prosperous and dynamic Europe. That has meant neither lazy affirmation of the region’s status quo nor efforts at destabilising transformation. It has required the right balance in dealing with a China whose growing economic, military and political strength is viewed with anxiety by many of the region’s peoples and as a potential strategic rival by the United States.

Obama’s policy towards China has built on the efforts of every presidential administration since Richard Nixon and is grounded in several fundamental principles. These include accepting the increased influence of a China that plays by international rules, building an extensive network of connections with Chinese elites and ordinary people and providing assurance to the region of the enduring nature of the US’ security commitments. The US also aims to maintain a formal framework of multilateral cooperation encompassing the United States, China and various regional states.

Major achievements have included the establishment of democracy in Myanmar; the US’ decision to join the East Asia Summit and begin efforts to turn it into a significant regional security forum; and the measurable strengthening of security relationships with Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN nations.

With China, Obama has taken steps to improve cooperation and transparency, along with measures to strengthen the security of the United States and its regional allies. The United States and China have concluded military-to-military agreements designed to avoid incidents on the high seas and in international air space. The Obama administration has worked with China to successfully freeze Iran’s nuclear weapons programme, place caps on greenhouse gases and halt cyber theft of US companies’ intellectual property.

The United States has also ramped up its naval presence in the South China Sea and, for the first time, comprehensively laid out its principles there — which were largely validated by the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling on the China–Philippines dispute. It has overseen a transfer of some of the US’ most advanced naval and air force systems to the Pacific, and it has reaffirmed US defence assurances to Japan covering Japanese-administered islands in the East China Sea challenged by China.

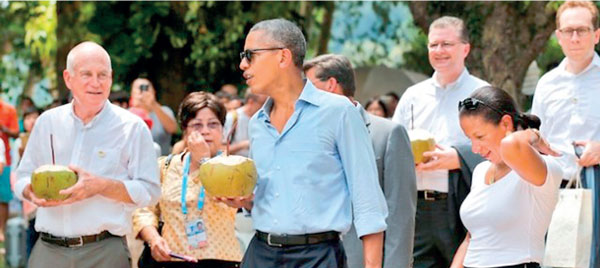

With President Obama having just held his last official meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, there are two principal challenges to the generally positive trajectory of US policy towards Asia.

The first is the continuing difficulties in managing and reacting to China’s rise. Will China address territorial conflicts peacefully in the South China Sea, cooperate in rolling back North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme, build a normal relationship with Japan and manage its differences with Taiwan? Will China work towards a politically sustainable trade and investment regime and dismantle nationalist and mercantilist policies that encourage other countries to erect retaliatory barriers and decrease global prosperity?

China, not the United States, will answer these questions, but the kind of relationship that the United States has with China will help shape the answers. Neither an American policy of containment nor one of isolationism will produce the desired outcomes to these challenges. None have been resolved during Obama’s time, but he has made ample progress and laid out a realistic and balanced framework that the next president would do well to heed.

The second is the domestic mood in the United States. Casual proposals by Donald Trump to allow Japan and South Korea to acquire nuclear weapons, to abandon US alliances if its partners don’t pay their ‘fair share’, and to impose 45 percent tariffs on China would individually and collectively undo the achievements of President Obama and his predecessors.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement (TPP) negotiations, a signature achievement of Obama’s Asia policy, may be a casualty of American domestic politics. If Congress doesn’t approve the TPP this year then approving some form of the TPP will become a priority for the next administration. Otherwise, people in Asia who have long looked to the United States as an essential partner may conclude that its interests do not include them.

(Courtesy East Asia Forum)

(Jeffrey Bader is a senior fellow at the John L. Thornton Center, Brookings Institute. From 2009–2011, he served as special assistant to the president of the United States for national security affairs at the National Security Council)

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago