04 Oct 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Public-Private Partnership (PPP) projects are gaining momentum globally as a means for delivering infrastructure.

Government capabilities to prepare, procure, and manage such projects are important to ensure that the expected efficiency gains are achieved. No systematic data currently exist to measure those capabilities in governments.

Benchmarking PPP Procurement 2017 is the first attempt to collect and present comparable and actionable data on PPP procurement on a large scale, by providing an assessment of the regulatory frameworks and recognized practices that govern PPP procurement across 82 economies.

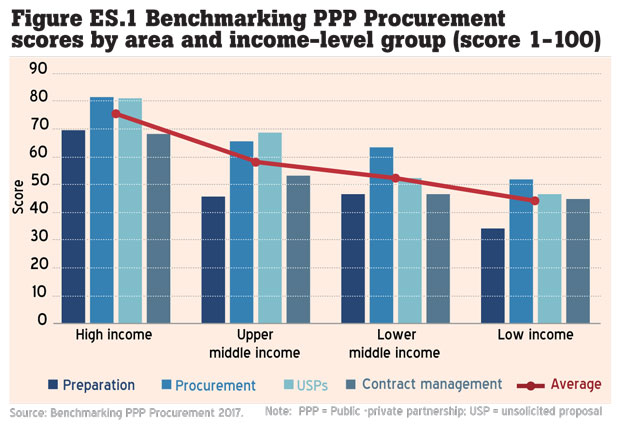

Benchmarking PPP Procurement 2017 presents an analysis of targeted elements aggregated into four areas that cover the main stages of the PPP project cycle: preparation, procurement, and contract management of PPPs, and management of Unsolicited Proposals (USPs). Using a highway transport project as a case study to ensure cross-comparability, it analyzes the national regulatory frameworks and presents a picture of the procurement landscape at the end of March 2016.

Income Vs performance

The average performance in each area varies across regions and income levels. The figure shows that higher the income level of the group, higher the performance in the four areas.

The data also show that the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) high income and Latin American and Caribbean regions perform at or above average.

Benchmarking PPP Procurement 2017 shows that across the four areas measured, most economies fall short of good practice. In particular, a significant number of economies have low scores in two areas: project preparation and contract management. Consequently, there is room for improvement specially in regulating the activities to be undertaken before launching the PPP procurement process as well as in preparing for those that will follow after the signature of the PPP contract, as illustrated in the examples below.

The 82 economies reflect a range of regulatory frameworks and institutional arrangements for PPPs. All have in place specific frameworks for regulating PPPs, with 71 percent either having a concession or a specific PPP law (25 percent of which coexist with a concession law), 11 percent having PPP guidelines or policies, and the remaining 18 percent resorting to the general procurement law to govern their PPP contracts. Although regulatory frameworks may differ, the fact that an economy uses a general procurement law does not prevent it from doing PPP projects. In fact, 13 out the 15 economies that use general procurement law had committed investments in PPPs in the past five years. PPP units are very common (85 percent of the economies measured have them), but only 16 percent of them play a leading role during the PPP procurement phase by for example conducting the tendering process.

The findings reveal a mixed picture in terms of approaches to ensuring that PPPs are fiscally sustainable and consistent with national investment programs. PPP fiscal management and assurance of the consistency of PPP projects with investment priorities are two means for ensuring that projects are fiscally sustainable and are selected on the basis of their strategic importance and impact rather than because of any expectation of savings through off-budget reporting.

Nearly three-quarters of the economies require the Ministry of Finance’s approval before launch of a PPP procurement process. Yet only 55 percent legally require consistency between the prioritizations of PPPs and other public investments—and only a quarter have detailed procedures for ensuring that consistency.

Rigorous assessments are essential for the preparation of sound projects, but many economies have not adopted specific appraisal methodologies. One of the main challenges that emerging markets face in attracting private sector investments is preparing a well-structured PPP project.

Approximately two-thirds of the economies surveyed require socioeconomic impact, affordability, risk identification, bankability, and comparative assessments (PPP versus traditional procurement) of a potential PPP project. However, only about one-third of these economies have adopted specific methodologies for conducting such assessments. In almost half of the economies, a market assessment is not required at all, and only about 10 percent have adopted a methodology for such an assessment. Thus, many economies are likely taking projects to market without having systematically measured market interest.

Onerous efforts

In conducting PPP procurement, many economies perform closer to recognized good practices. Yet there is still room for improvement in two areas: (a) the minimum time granted to potential bidders to submit their bids and (b) the approach to handling sole bidders.

PPP projects are complex and require onerous efforts and consequently sufficient time to prepare strong, sensible bids. Nonetheless, 40 percent of the economies surveyed either do not specify a minimum period for the preparation of bids or require a period of fewer than 30 days. Moreover, only 15 percent of the economies have a detailed process to address cases when only one bid is received, hence leaving it to the discretion of the procuring authority to set the process.

There is considerable scope to improve practices related to the disclosure of information on PPPs. A transparent, competitive process is essential to achieving better outcomes for projects and efficiency gains in infrastructure. Having a transparent process requires making publicly available all the information relevant to ensuring a competitive process. Most of the economies do so for the tender notice (93 percent) and the PPP award (74 percent), but only 23 percent publish the PPP contract, and very few publish it online. Furthermore, a transparent information system is essential during the contract management phase of PPP, yet only 16 percent of the economies require data to be made publicly available. Although in most of the economies the private partner must periodically provide performance information and the procuring authority must gather it (60 percent and 73 percent, respectively), in only 16 percent of economies is this information required to be made publicly available. Renegotiation and disputes of contracts may be inevitable in some cases, but one-third of the economies do not regulate them comprehensively.

Renegotiations and disputes can erode the achievement of the expected benefits of a PPP project—and if frequent, can trigger opportunistic behavior in future PPP projects. The economies measured handle renegotiations differently, with 31 percent either not addressing this issue in the regulatory framework or considering it solely a contractual matter. Although the regulatory frameworks of most of the economies (85 percent) mention dispute resolution mechanisms for PPPs, only 27 percent of those economies establish specific mechanisms to address the disputes.

Non-regulation of USPs

A significant number of economies do not regulate USPs. Among those that do, very few have a clear process for evaluating them.

The difficulty with USPs lies in getting the right balance between encouraging private companies to submit innovative project ideas and maintaining the transparency and efficiency gains of a competitive tender process. Of the economies measured, 32 percent have no provisions that specifically regulate USPs.

Even among economies where such provisions exist, only 21 percent provide a detailed framework for ensuring consistency with government priorities, and only 13 percent guarantee a period of more than 90 days for proposal submission—that is, a sensible length of time to introduce competitive tension, challenging the original proponent in a competitive tendering process.

(This is the Executive Summary of the latest report by the World Bank on public-private partnerships titled ‘Benchmarking Public-Private Partnership Procurement 2017’)

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 6 hours ago