04 Sep 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Colin Mackerras

At a time when globalisation from the West appears to be in retreat, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a potent symbol of the rise of China-based globalisation.

The BRI, part of Xi Jinping’s ‘China dream’ to ‘revitalise the Chinese nation’, is a two-fold project: a belt to link the great Eurasian continent with overland railways, highways, pipelines and other infrastructure, and a road to link China with Southeast Asia and even Africa through ports and other maritime linkages. Collectively, it was known as ‘One Belt, One Road (OBOR)’ but is now usually referred to as the BRI.

The BRI comes at a time when global divisions are intensifying. Diverse nationalisms with the potential for serious conflict are becoming more marked. Economic globalisation and free-trade once seemed so eminently desirable that few dared go against them. Yet, there is now less consensus about the benefits.

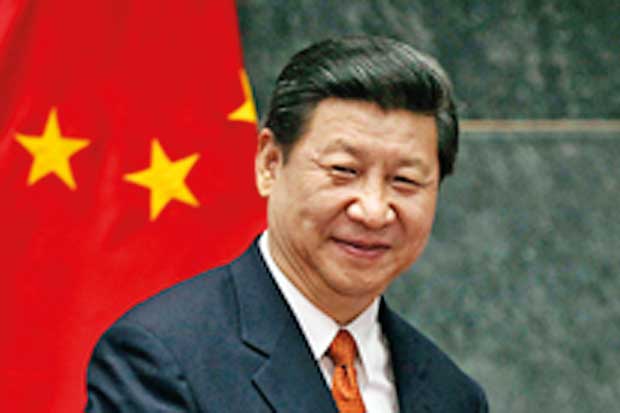

The BRI’s primary aim is economic. One major objective is to reduce disparities in China by spurring growth in the country’s underdeveloped hinterland and rust belt. At the World Economic Forum in January 2017, it was Xi Jinping — the first Chinese President to attend — who took the lead in supporting globalisation and opposing protectionism. Jinping stated flatly in the forum’s opening speech that “just blaming economic globalisation for the world’s problems is inconsistent with reality and it will not help solve the problems”.

Late in 2014, the Chinese government set up the New Silk Road Fund and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank to promote infrastructure that would support the trade and other economic linkages involved in the BRI. Around the same time, operations on a railway line linking Yiwu, a county-level city in the Zhejiang Province, with the Spanish capital Madrid, had begun. Another major development is the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Some commentators see the primary objective of the BRI as domestic, believing it is largely aimed at reducing disparities. It is also likely that China sees the BRI as a potential bulwark against Islamist terrorism in Xinjiang and along its western borders, since economic development is the best reinforcement against political instability. But the foreign policy dimensions of the BRI are also extremely important.

The investment promised by the BRI is large enough to invite comparison with the US Marshall Plan that revived the European economies in the wake of World War II. Less positively, it is suggested that China is trying to economically take over the countries of Central Asia and elsewhere.

In May 2017, Jinping sponsored the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. The attendees included more than 30 heads of organisations and heads of states such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Indonesian President Joko Widodo, as well as the then Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. The attendance suggests great enthusiasm for the BRI at a government level.

One country that is definitely not enthusiastic about the BRI is India, who is wary about China’s increasing ties with Pakistan and Russia. There were no Indian representatives at the forum in May. The advance of Indian troops in June to stop China building a road in Bhutan resulted in a serious faceoff, although negotiations resulted in a solution late in August, the deterioration in relations in more long-term. Along with several other countries, India is nervous about the strategic implications of China’s access to Pakistan’s deep-water port of Gwadar, which would open China and its land-locked territory of Xinjiang to the Persian Gulf.

In some respects India and China are trying to cooperate. India (and Pakistan) joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 2016, while the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Forum links the two Asian giants in a grouping loosely united to promote the interests of emerging market economies vis-à-vis the West. But long-term rivalry and hostility between China and India continues to make sustained cooperation difficult.

While governments are mostly keen on the BRI, viewing it as offering economic expansion and greater prosperity, many ordinary people are less convinced. China’s image in Central Asia is highly mixed and there are people who view China’s economic expansion as inevitable but pernicious. They resent the fact that Chinese companies bring their own workers with them, so local people gain little employment.

Opinion in the West is also divided. While many observers and businesspeople see opportunities in the BRI for profits and growth, others doubt project viability and feasibility. Sceptics regard it as too inefficiently organised to be sustainable and the main countries involved as not committed or economically competent enough to make it work. Many are suspicious of Chinese motives, regarding it as a plot to regain China’s traditional power over regions to its west. This is in part the fear of China and anxiety that the West and its interests will be eclipsed.

It is unclear if the BRI will succeed in the short term. China’s image appears to have worsened over the last few years and is now undergoing another serious downturn due to the global reaction over Nobel Laureate Liu Xiaobo’s death. But what the West thinks may not be the crucial factor in the long term. In all likelihood, the impact of the BRI over the next several decades will be huge. It will transform interchanges across Eurasia and with Africa and be a major boost to China’s world economic and strategic influence.

(Colin Mackerras is Emeritus Professor at Griffith Business School, Griffith University)

25 Nov 2024 20 minute ago

25 Nov 2024 45 minute ago

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago